What Will You Make Room for in Your Wagon?

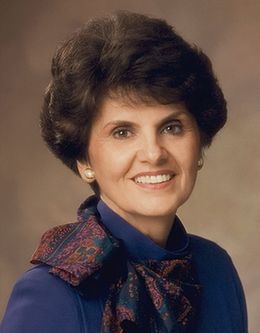

Young Women General President

November 13, 1990

Young Women General President

November 13, 1990

I’m grateful, brothers and sisters, for the privilege of being on this campus and participating in any way in the mission of this university and your part in it as you accept the opportunity to learn and prepare to go forth and serve. The thoughts I would like to share with you today I believe fit under the title “What Will You Make Room for in Your Wagon?” It might be considered a self-talk message for my benefit as well as for yours.

A number of years ago, when I was a beginning teacher in elementary school, I had the superintendent’s daughter in my fourth-grade class. She had some learning difficulties. I was anxious for her to learn as quickly as possible. After many attempts with only a blank stare in response to my efforts to teach her long division, at one moment she jumped up and excitedly announced, “Finally you said it right. I’ve got it. I’ve got it.” I pray that the Spirit of the Lord will bless us so that the things I have prepared will be of help to you.

Some time ago, one of the students on this campus called my home to report what sounded to me like a condition of epidemic proportions. It was just before finals. Shelly, who happens to be my niece, explained that she and her roommates were stressed out and needed a place to escape for the weekend. I, of course, was delighted to provide the place. They said there had hardly been a weekend or even a day when they had not been completely overloaded. “So much to do and so little time” was their comment as they talked of schedules, commitments, expectations, pressures, and even some anxieties about dates, deadlines, decisions, finances, future obligations, and unlimited opportunities.

With so many wonderful opportunities, maybe you could take advantage of it all if you could stay up long enough, get up early enough, run fast enough, and live long enough. It has been said that if you’re willing to burn the candle at both ends, you might get by, but only if the candle is long enough.

We all seem to be looking for ways to do more faster. Nowadays we can watch one TV show while we tape another and fast forward to eliminate the commercials. We read condensed books and eat fast foods. Some would have us believe that the more appointments we have in our day planner, the more successful we are. The plague of our day is the thought repeating in our minds like the steady ticking of a clock: “I do not have time. I do not have time.” And yet we have all there is.

Today we read of stress management, the Epstein-Barr Syndrome, overload, and over-exhaustion. In an effort to escape some of the pressures of our day, we see an increased consumption of alcohol, the improper use of prescription drugs, other related social ills, immorality, and even suicide. And yet never before has there been such evidence of increased knowledge and expanding opportunities. It has been said that “We have exploded into a free-wheeling multiple-option society” (John Naisbitt, Megatrends (New York: Warner Books, 1982), introduction, p. xxiii). We are faced with the burden of too many choices. I have discovered that even the purchase of a simple tube of toothpaste poses many options considering brand, flavor, size, cost, ingredients, and promises. We speak of high tech and high touch, hardware and software, and find we need increasing self-reliance as the options multiply at an accelerated pace.

William James, the noted American psychologist and philosopher, states:

Neither the nature nor the amount of our work is accountable for the frequency and severity of our breakdowns, but their cause lies rather in those absurd feelings of hurry and having no time, in that breathlessness and tension; that anxiety . . . , that lack of inner harmony and ease. [Quoted by William Osler in A Way of Life (New York: P. B. Hoeber, 1937), p. 30]

Too often we allow ourselves to be driven from one deadline, activity, or opportunity to the next. We check events off our calendar and think, “After this week things will let up” or “After this semester” or “After graduation, then the pressure will ease.” We live with false expectations. Unless we learn to take control of the present, we will always live in anticipation of better days in the future. And when those days arrive, we shall still be looking ahead, making it difficult to enjoy the here and now. The beautiful fall leaves come and go, and in our busyness we miss them. “Give another season, we’ll do better,” we say.

We live in a time when we can do more, have more, see more, accumulate more, and want more than in any time ever known. The adversary would keep us busily engaged in a multitude of trivial things in an effort to keep us distracted from the few vital things that make all of the difference.

When we take control of our lives, we refuse to give up what we want most, even if it means giving up some of what we want now. Former president Jeffrey R. Holland reminded students to “postpone your gratification so you don’t have to postpone your graduation” (Jeffrey R. Holland, “The Inconvenient Messiah,” in BYU Speeches, 1981–82, p. 82). And how is this to be accomplished?

I believe the most destructive threat of our day is not nuclear war, not famine, not economic disaster, but rather the despair, the discouragement, the despondency, the defeat caused by the discrepancy between what we believe to be right and how we live our lives. Much of the emotional and social illness of our day is caused when people think one way and act another. The turmoil inside is destructive to the Spirit and to the emotional well-being of one who tries to live without clearly defined principles, values, standards, and goals.

Principles are mingled with a sense of values. They magnify each other. Striving to live the good life is dependent upon values to measure our progress as we learn to like and dislike what we ought to. We learn to be honest by habit, as a matter of course. The question shouldn’t be “What will people think?” but “What will I think of myself?” We must have our own clearly defined values burning brightly within. Values provide an inner court to which we can appeal for judgment of our performance and our choices.

We live in a time when too often success is determined by the things we gather, accumulate, collect, measure, and even compare in relation to what others gather, accumulate, collect, measure, and compare. This pattern of living invites its own consequences and built-in stress. Maybe you heard of the woman who received a call from her banker explaining that she was overdrawn, to which she promptly replied, “No, sir, I am not overdrawn. My husband may have under-deposited, but I am not overdrawn.”

It is possible that we try to overdraw from our time bank and suffer the nagging and debilitating stress of bankruptcy. The difference, however, is more significant than our money bank. Only twenty-four hours a day is deposited for an indefinite period of time. No more and no less.

It is as we learn to simplify and reduce, prioritize and cut back on the excesses that we have enough time and money for the essentials, for all that we ultimately want in the end and even more.

This fall some friends came to our home with their children and brought with them a case of the most beautiful, large peaches I have ever seen. They were almost unbelievable in their size, their beauty, and their flavor. Brother Pitt explained that they had just won first prize at the county fair for their peaches, and they had an orchard full of them. I asked how you produce such remarkable fruit, and the family was eager to explain. “We learned how to prune the peach trees and thin the weak fruit,” they said. “It’s hard work and must be done regularly.”

“We also learned what happens when you don’t prune,” said one of the children. Their father had wisely suggested that three trees in the orchard be left to grow without the harsh results of the pruning knife. They explained to me that the fruit from these trees was not only very small in size but did not have the sweet taste of the other fruit. The lesson was obvious. There was no question in their minds about the far-reaching value of careful pruning.

In an article in BYU Today entitled “Misplaced Pride” by McKinley Tabor, speaking at an ethics conference for the Marriott School of Management, he shared his feelings. Reflecting back regretfully on some misplaced priorities, he said,

I was aggressive in wanting to own things, in wanting to make a lot of money, in wanting to be the big duck in a little pond. Now I focus on things like my children, on my family life in general, on experiencing things instead of owning things. I like to go places and see new things and meet new people where before I liked to own cars and have big bank accounts. The things that are important to me now are things that stay with you a lot longer than a dollar bill. [McKinley Tabor, “Misplaced Pride,” BYU Today, July 1989, pp. 17–19]

In the book The Star Thrower, Loren Eiseley writes of the beaches of Costabel and tells how the tourists and professional shell collectors, with a kind of greedy madness, begin early in the morning in their attempts to outrun their less-aggressive neighbors as they gather, collect, and compete. After a storm, people are seen hurrying along with bundles, gathering starfish in their sacks. Following one such episode, the writer says:

I met the star thrower. . . .

. . . He was gazing fixedly at something in the sand.

Eventually he stooped and flung the object beyond the breaking surf. . . .

. . . “Do you collect?” [I asked.]

“Only like this,” he said softly. . . . “And only for the living.” He stooped again, oblivious of my curiosity, and skipped another star neatly across the water.

“The stars,” he said, “throw well. One can help them.” . . .

. . . For a moment, in the changing light, the sower appeared magnified, as though casting larger stars upon some greater sea. He had, at any rate, the posture of a god. . . .

I picked [up] and flung [a] star. . . .

. . . I could have thrown in a frenzy of joy, but I set my shoulders and cast, as the thrower in the rainbow cast, slowly, deliberately, and well. The task was not to be assumed lightly, for it was men as well as starfish that we sought to save. [Loren Eiseley, The Star Thrower (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978), pp. 171–72, 184]

While gatherers carry bags weighed down with the accumulation of their possessions, star throwers find their joy in picking up those who would otherwise die on the sandy beach.

Like the Star Thrower, often those who have nothing visible to show for their labors are those individuals who are filled, rewarded, and energized by a labor that invigorates, motivates, inspires, and has a purpose of such far-reaching significance that they are driven by a power beyond themselves. This power is most often felt when we are in the service of our fellow beings, for in that service, as King Benjamin taught, we are in the service of our God (Mosiah 2:17).

We read about the pioneers who, in the early history of the Church, left their possessions, “their things,” and headed west. Those who were with the handcart company who would push or pull their carts into the wilderness would give much thought to what they would make room for in their wagons and what they would be willing to leave behind. Even after the journey began, some things had to be unloaded along the way for people to reach their destination.

In our season of abundance and excess, even while we are counseled to reduce and simplify, there will be a high level of frustration until we understand the value of pruning. When someone asks the question, “How do you do it all?” our answer should be, “We don’t.” We must be willing to let go of many things but defend with our lives the essentials.

Now I believe it would be very easy for an inexperienced gardener to approach the task of reducing and cutting back with such vigor that he might take a saw and cut the tree down the center, through the trunk, and into the roots. Surely it would be cut back, but what of the hope for the fruit? Wise pruning, like good gardening, takes careful thought. It is only when you are clear in your mind concerning your values that you are free to simplify and reduce without putting at risk what matters most. Until we determine what is of greatest worth, we are caught up in the unrealistic idea that everything is possible.

Thomas Griffith, a contributing editor for Time magazine, once summarized the problem this way. Describing himself as a young man, he said,

I thought myself happy at the time, my head full of every popular song that came along, the future before me. I could be an artist, a great novelist, an architect, a senator, a singer; having no demonstrable capacity for any of these pursuits made them all appear equally possible to me. All that mattered, I felt, was my inclination; I saw life as a set of free choices. Only later did it occur to me that every road taken is another untaken, every choice a narrowing. A sadder maturity convinces me that, as in a chess game, every move helps commit one to the next, and each person’s situation at a given moment is the sum of the moves he has made before. [Thomas Griffith, The Waist-High Culture (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1949), p. 17]

When we decide what is essential, we are released from the gripping position of doubtful indecision and confusion. It is while a person stands undecided, uncommitted, uncovenanted, with choices waiting to be made, that the vulnerability of every wind that blows becomes life threatening. Uncertainty, the thief of time and commitment, breeds vacillation and confusion.

When our choices and decisions are focused on the accumulation of visible possessions and valuable materials, we may find that the acquisition of these things feeds an insatiable appetite and leaves us increasingly hungry. In 2 Nephi the Lord warns us:

Wherefore, do not spend money for that which is of no worth, nor your labor for that which cannot satisfy. Hearken diligently unto me, and remember the words which I have spoken; and come unto the Holy One of Israel, and feast upon that which perisheth not, neither can be corrupted, and let your soul delight in fatness. [2 Nephi 9:51]

When our time is spent in the accumulation of experiences that nourish the spirit, we see with different glasses things that others do not see and cannot understand.

In the book The Little Prince, by Antoine de Saint-Exupery, we read about the importance of values and relationships. The fox says to the Little Prince, “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye” (Antoine de Saint-Exupery, The Little Prince [New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1943], p. 70).

One of the great examples of acquiring invisible possessions of priceless value comes from the dramatic story told of Zion’s Camp. The Missouri Saints were expelled from Jackson County in late November 1833. Four months and twelve days later, 24 February 1834, Joseph Smith was instructed to organize an army to restore the Saints to their rightful ownership of land in Jackson County. The group would march 1,000 miles in four months. They would suffer sickness, deprivation, and severe testing of every physical kind.

Heber C. Kimball said, “I took leave of my wife and children and friends, not knowing whether I would see them again in the flesh.” It was not unusual for them to march thirty-five miles a day, despite blistered feet, oppressive heat, heavy rains, high humidity, hunger, and thirst. Armed guards were posted around the camp at night. At 4:00 a.m. the trumpeter roused the weary men with reveille on an old, battered French horn. Zion’s Camp failed to help the Missouri Saints regain their lands and was marred by some dissension, apostasy, and unfavorable publicity, but a number of positive results came from the journey. Zion’s Camp chastened, polished, and spiritually refined many of the Lord’s servants. When a skeptic asked what he had gained from his journey, Brigham Young promptly replied, “I would not exchange the knowledge I have received this season for the whole of Geauga County” (“Church History in the Fulness of Times,” prepared by the Church Educational System, Salt Lake City, Utah, pp. 143–51).

From among the members of Zion’s Camp the Lord selected those who would lead his church during the next five decades. From the viewpoint of preparation, the Zion’s Camp experiences proved to be of infinite value during the formative years of the Church. Those Saints were tried and tested. They learned what they stood for, what they were willing to live and die for, and what was of highest value.

Today our tests are different. We are not called to load our wagons and head west. Our frontier and wilderness are of a different nature, but we too must decide what we will make room for in our wagons and what is of highest value.

In recent months the Museum of Church History and Art has opened a new exhibit entitled “A Covenant Restored.” As you enter, you begin to remember in a new way the price paid by those who came before us. Standing at the edge of a very rough-hewn log cabin, you feel something of the commitment and sacrifice those early Saints made. Erected immediately next to this very humble dwelling, where life was sustained by men and women with values, commitments, and covenants, we see a replica in actual size of the beautiful window of the historic Kirtland Temple.

As you move along the path through the museum, you are emotionally drawn from Kirtland on through the experiences that finally brought the Saints to the valley of the Great Salt Lake. At one point you see the temple as the center of everything that drove them through these incredible circumstances, and something happens inside. I pondered in ways that I haven’t before the significance of the temple in their lives and ours.

I stood at the side of a handcart and wondered, “How did the family decide what they would make room for in their wagons?” And what will we make room for in our wagons? What is of greatest importance in life?

One year as I was driving myself and my niece Shelly, who was then seven years old, back from a trip to Vernon, British Columbia, I had an experience that has helped me as I try to improve my ability to prune wisely and to load or unload my wagon, as the case may be.

During the trip when we were not playing the tape “Winnie the Pooh” for the hundredth time, Shelly would be asleep in the backseat of the car, and I had many hours and many miles to weigh, compare, and wonder. I had gone to Canada to take care of my sister’s family of nine children while she was in the hospital with her tenth baby. After a week of doing laundry, matching socks, tending to paper routes, meals, lessons, car pooling, bedtime stories, lunch money, settling disputes over time spent in the bathroom, finding shoes, and planning for family home evening, I felt overwhelmed to say the least. At the appointed time my sister returned with a babe in arms. I stood in awe and reverence as I watched her step back into that routine with the ease and harmony of a conductor leading a well-trained orchestra with each player coming in on cue. It was a miracle to me.

As I thought of her life and mine, I began measuring what I was not doing in comparison to what she was doing. We do that, you know. I began wondering and feeling discouraged, despondent, even depressed.

At that moment, somewhere between the Canadian border and Spokane, my father’s voice came into my mind. He had passed away two years before, but his voice was as clear as though he were sitting by my side. “My dear,” he said, “don’t worry about the little things. The big things you agreed to before you came.” And for the rest of the journey, between moments of listening to “Winnie the Pooh,” I asked myself over and over again, “What are the big things in life? What is essential? What is the purpose of life?” I share this experience with you, my brothers and sisters, because I believe there are times when these same questions weigh heavily on your mind.

The years have passed since that experience, and Shelly has traded Winnie the Pooh for the more important things. She has just recently received her mission call to New Zealand. She is now willing to leave important things behind, including ballroom dancing, which for Shelly borders on being essential, to go forth and teach the real essentials, the gospel of Jesus Christ. Elder John A. Widtsoe wrote:

In our pre-existent state, in the day of the great council, we made a certain agreement with the Almighty. The Lord proposed a plan, conceived by him. We accepted it. Since the plan is intended for all men, we become parties to the salvation of every person under that plan. We agreed, right then and there, to be not only saviors for ourselves, but measurably saviors for the whole human family. We went into a partnership with the Lord.

The working out of the plan became then not merely the Father’s work, and the Savior’s work, but also our work. The least of us, the humblest, is in partnership with the Almighty in achieving the purpose of the eternal plan of salvation. That places us in a very responsible attitude towards the human race.

Like the Star Thrower, it is in helping to save others that we find our pleasure and joy, our labor, and ultimately our glory. Elder Widtsoe further states:

If the Lord’s concern is chiefly to bring happiness and joy, salvation, to the whole human family, we cannot become like the Father unless we too engage in that work. There is no chance for the narrow, selfish, introspective man in the kingdom of God. He may survive in the world of men; he may win fame, fortune and power before men, but he will not stand high before the Lord unless he learns to do the works of God, which always points toward the salvation of the whole human family. [Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, October 1943, p. 289]

Our understanding of and commitment to the covenants we have made with God are the essentials. Our day-to-day interactions, our integrity, our moral conduct, our willingness to “bear one another’s burdens, that they may be light; . . . to mourn with those that mourn; . . . and comfort those that stand in need of comfort, and to stand as witnesses of God at all times and in all things, and in all places” (Mosiah 18:8–9) are at the very heart of our earth-life experience. Every decision should be made with that goal in mind, and we should expect it to be difficult, very difficult. We are to be tried and tested in all things (see D&C 136:31).

Some time ago, my husband and I visited the Mormon cemetery at Winter Quarters, a monument to family members young and old buried in graves along the trail as their families continued westward toward the Rocky Mountains. Of those people who had vision and faith in God, we read,

There are times and places in the life of every individual, every people, and every nation when great spiritual heights are reached, when courage becomes a living thing . . . when faith in God stands as the granite mountain wall, firm and immovable. . . . Winter Quarters was such a time and place for the Mormon people. [Heber J. Grant, remarks at the dedication of the Winter Quarters Monument, 1936]

A person who only looks for the visible may draw from this pioneer experience what appears to be an obvious conclusion—families perished. But in the eternal perspective, they did not. It was their willingness to sacrifice everything, even life if necessary, that would ensure the eternal lives of these families.

And what of our Winter Quarters and Zion’s Camp experiences? Times of difficulty try the faith of all who profess to be Latter-day Saints and follow the prophets. We are walking in the well-worn paths of those who preceded us in the quest for Zion. Help and comfort are available to us through sources beyond our own immediate strength, just as they were for those who have gone before us.

It has been said that trials are at the core of saintliness. Through our covenant relationship with Jesus Christ, we do all that we can do, and by the grace of God he does the rest.

The Lord has promised us,

Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.

Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me; for I am meek and lowly in heart: and ye shall find rest unto your souls.

For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light. [Matthew 11:28–30]

One of the early pioneers testified,

I have pulled my handcart when I was so weak and weary from illness and lack of food that I could hardly put one foot ahead of the other. I have looked ahead and seen a patch of sand or a hillslope, and I have said, “I can go only that far and there I must give up for I cannot pull the load through it.” . . . I have gone on to that sand and when I reached it, the cart began pushing me. I have looked back many times to see who was pushing my cart, but my eyes saw no one. I knew then that the angels of God were there. [Relief Society Magazine, January 1948, p. 8, as quoted in James E. Faust, “The Refiner’s Fire,” Ensign, May 1979, p. 53]

It is with faith in God that we must condition ourselves to let go of everything if necessary. For some of us it may require unloading bad habits, attitudes, disobedience, arrogance, selfishness, and pride.

Just this summer our family came in possession of the first letter written to my grandmother by her mother when my grandmother left her home in England as a young immigrant. She left everything behind because someone taught her of the gospel of Jesus Christ. She joined the Saints in America and eventually moved to Canada. For fear of being persuaded to remain in England, she did not tell her family of her conversion to the Church or her plans to leave until after. That first letter received from her mother reads in part:

My dearest daughter. . . whatever on earth has caused you to go out of your own country and away from all your friends, I cannot imagine. You say, “Don’t fret.” How do you think I can help it when such a blow as that come to struck me all up in a heap? You say you are happy, but I can’t think it, for I am sure I could not have been happy to have gone into a foreign country and left you behind. You say you will come again, but I don’t think you will hesitate your life over the deep waters again. When I think about it, I feel wretched. You had a good place and a good home to come to whenever you liked. And I must say that I loved the very ground you walked upon, and now I am left to fret in this world. But still, all the same for that, I wish you good luck and hope the Lord will prosper you in every way. I remain, your loving Mother. [Personal Files]

They never saw each other again in this earth life. And none of her family joined the Church. However, their temple work has been done for them.

What is it that drives a people to sacrifice all if necessary to receive the blessings available only in the temple? It is their faith and a spiritual witness of the importance of our covenants with God and our immense possibilities. It is in the temple, the house of the Lord, that we participate in ordinances and covenants that span the distance between heaven and earth and prepare us to return to God’s presence and enjoy the blessings of eternal families and eternal life.

A few weeks after my visit to the Kirtland Temple, I was standing at the water’s edge of the baptismal font in the small Manila Temple in the Philippines. Many of those dear Saints had traveled for three days in the heat and humidity by boat to come and participate in sacred ordinances available only in the temple. On one of these islands in a small, primitive nipa hut, I visited with a family of Latter-day Saints. A beautiful young fourteen year old in this humble setting listened intently while her father explained that in 1991, by saving all they could, the family would have enough to go to the Manila Temple, where they could be sealed as a family forever.

When we understand that our covenants with God are essential to our eternal life, these sacred promises become the driving force that helps us lighten our load, prioritize our activities, eliminate the excesses, accelerate our progress, and reduce the distractions that could, if not guarded, get us mired down in mud while other wagons move on. If any of you are burdened with sin and sorrow, transgression and guilt, then unload your wagon and fill it with obedience, faith, and hope, and a regular renewal of your covenants with God.

President Kimball reminded us, “Since immortality and eternal life constitute the sole purpose of life, all other interests and activities are but incidental thereto” (Spencer W. Kimball, The Miracle of Forgiveness [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1969], p. 2).

Does that suggest that there should be no football, fashion, fancy food, or fun? Of course not. But these things are incidental to the real purpose of our earth life. Our purpose in life provides the compass and keeps us on course while we enjoy the journey. If we are found to be long faced, sober, and sanctimonious, we will be guilty of portraying a false image of the joys of the gospel. As the pioneers traveled, there was singing and dancing. In their camaraderie, a covenant people built a community with a strong sense of brotherhood and sisterhood. People with common values and goals strengthened one another in joy and sorrow, in sickness and health. They sustained one another as they prepared to make and keep sacred covenants.

There is a unique strength that comes when a group of faithful Saints, however large or small, band together and encourage each other in righteousness.

As we take an inventory of the things we are carrying in our wagons and make decisions about what we will be willing to leave behind and what we will cling to, we have guidance. The Lord has given us a great promise to which I bear my testimony. He has said,

Therefore, if you will ask of me you shall receive; if you will knock it shall be opened unto you.

Seek to bring forth and establish my Zion. Keep my commandments in all things.

And, if you keep my commandments and endure to the end you shall have eternal life, which gift is the greatest of all the gifts of God. [D&C 14:5–7]

We live in a time when the things of the world would, if possible, press in upon us and close out the things of God. May we turn our attention from the glitter of the world as we give thanks for the glory of the gospel, in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

Ardeth G. Kapp was general president of the Young Women of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 13 November 1990.