Challenges to the Mission of Brigham Young University

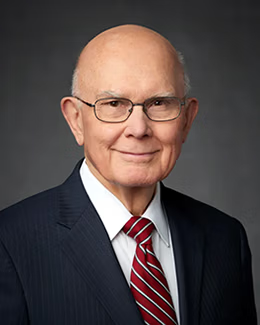

of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles

April 21, 2017

of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles

April 21, 2017

To accomplish its mission, BYU must have all parts of its community united in pursuing it.

I am pleased to be here in this important gathering of BYU leaders, whom I last addressed in your BYU leadership meeting in August 2014. As I said there:

[I] firmly believe that it is the destiny of Brigham Young University to become what those prophetic statements predicted it would become. But inherent in being the University of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is the reality that this great goal will not be attained in exactly the same way that other universities have achieved their greatness. With your help, it will become the great university of the Lord—not in the world’s way but in the Lord’s way.1

We love the way President Kevin J Worthen has been stressing the mission statement of this university. That emphasis is essential and timely to resist challenges—both external and internal. I will speak of the external first.

I don’t need to tell you that there are great external pressures for BYU to conform to some laws, regulations, accrediting requirements, and standards of various professional associations that would prevent or impede the attainment of our institutional and Church goals. This is an old problem with which I have had considerable personal experience and which I merely reference here with the words “same-sex dormitories and Title IX.”

President Worthen has spoken of an important cause of such external challenges. For many years, religiously affiliated colleges and universities have been steadily disappearing, some by formal disaffiliation and some by institutional drift. Today they are a tiny minority without clear definitions to distinguish them from private secular and even public institutions. President Worthen said:

So we don’t know how many universities are religiously affiliated. And of those that are, some are headed out the door. And the trend is so strong that Mark Tushnet, who is quite well known in legal education, [is referenced by Robert John Araujo, who] said that any religiously affiliated university “‘will find it extremely difficult’ to maintain this [religious] affiliation if it also seeks to attain or preserve a national reputation.” In other words, there are those who say, “You have a choice—you can either be secular or second-rate. Make your choice.” Now, this is not a lost cause by any stretch of the imagination, but that’s the trend, and we are sort of a countertrend for many reasons.2

These external challenges are mostly being handled by the administration of the university—capably, I am pleased to say—with the understanding and support of the rest of you leaders. We thank you for that.

More good news about our efforts to differ from the world’s secular way of education is that we have some friends and supporters, even in secular places. Some unexpected evidence of this was published by David Brooks, the respected New York Times columnist.3 Raised in a Jewish home in New York City, Brooks explained, “I’ve spent much of my life with secular morality. I think the most spiritual institution I would go into is Whole Foods.”4 As he faced an audience of Christian educators, he reflected on his experience teaching students at Yale University. He said, “My students are wonderful; I love them,” but they “are so hungry for spiritual knowledge.”5 Speaking of those students, Brooks said:

They have a combination of academic and career competitiveness and a lack of a moral and romantic vocabulary that has created a culture that is professional and not poetic, pragmatic and not romantic. The head is large, and the heart and soul are backstage. . . .

I think that God has given us four kinds of happiness. . . . Fourth [is] transcendence—an awareness of one’s place in a cosmic order; a connection to a love that goes beyond the physical realm; a feeling of connection to unconditional truth, love, justice, goodness, beauty and home. . . .

Many of our institutions, and especially our universities, don’t do much to help our graduates achieve that transcendence. But for Christian universities and other religious institutions, this is bread and butter. This is the curriculum. . . . You [Christians] have a way of being that is not all about self. You have a counterculture to the excessive individualism of our age. You offer an ideal more fulfilling and more true and higher than the ideal of individual autonomy. . . .

What I’ve tried to describe is this task of helping young people build the commitments, the foundations of their lives. A lot of the schools I go to do a great job at many other things, but integrating the faith, the spirit, the heart and the soul with the mind is not one of them.6

Here, in just a few lines, is one of Brooks conclusions—given as he was speaking to Christian educators and something that is fully applicable to BYU:

You guys are the avant-garde of 21st-century culture. You have what everybody else is desperate to have: a way of talking about and educating the human person in a way that integrates faith, emotion and intellect.7

Today I wish to concentrate mostly on internal challenges. These are the ones you administer, under the leadership of the university administration. These are the subject of BYU’s 1981 mission statement, which President Worthen has stressed so consistently.

Here I quote from President Worthen’s comprehensive and persuasive first address at the BYU annual university conference in August 2014. I do so with complete approval of his emphasis.

This morning I would like to review with you some of the key principles in our mission statement with the ultimate aim of helping us better understand the great cause in which we are engaged and the ways in which each of us can better carry out our roles in this cause. . . .

At the end of the day, students are the product we produce, to put it in business terms. How they turn out—what they do and, more important, who they are—is the ultimate metric by which our work will be measured. . . .

In short, we are and will remain a student-centric university, one that focuses on the development of our students above all else. With every major decision we make, we need to ask ourselves how this endeavor can enhance the educational experience of our students. . . .

. . . So it is important for us to understand what our role is in the quest for perfection and eternal life in the lives of these students.8

Later in his message, President Worthen said:

The mission statement outlines the . . . “major educational goals” we have for our students. The curricular aspects of those goals are outlined in the topic sentences of the three middle paragraphs of the mission statement:

1. “All students at BYU should be taught the truths of the gospel of Jesus Christ.”

2. “Because the gospel encourages the pursuit of all truth, students at BYU should receive a broad university education.”

3. “In addition to a strong general education, students should also receive instruction in the special fields of their choice.”9

Let me quote another key paragraph from President Worthen’s message:

If the only insights that students receive on gospel truths are in their religion classes, we will not be that different from other good universities to which an institute of religion is attached. What will truly make us unique—and what we must uniquely do well—is to meet the challenge set forth by President Spencer W. Kimball [in his great 1967 talk “Education for Eternity”]: “That every professor and teacher in this institution would keep his [or her] subject matter bathed in the light and color of the restored gospel and have all his [or her] subject matter perfumed lightly with the spirit of the gospel.”10

Similarly, in his message to this important group of leaders almost three years ago, President Russell M. Nelson spoke of BYU’s importance to the Church, adding that “at BYU we must ally ourselves even more closely with the work of our Heavenly Father. His goal for eternal life for His children, as stated in Moses 1:39, should be our goal.”11 And the BYU mission statement says, “To succeed in this mission the university must provide an environment enlightened by living prophets.”12

To accomplish its mission, BYU must have all parts of its community united in pursuing it. I quote from President Worthen again, this time when he spoke in August 2015:

I believe that this threefold description [that the students study, the faculty teach, and the staff serve] not only makes clear that every person involved in this enterprise has a role to play but, more important, also describes the threefold responsibility that every person shares no matter what his or her particular role may be.13

All of these instructions are, of course, familiar, but I believe all will agree that we are still knowing them better than we are doing them. There is room for improvement.

Now, in the midst of our long-standing challenges, external and internal, we have a new complexity. Our BYU name is now shared with Idaho and Hawaii and, just recently, with BYU–Pathway Worldwide. Today Brigham Young University not only needs to resist being homogenized by the world but must also avoid being confused with its sister institutions. But beyond that, its familial relationships in the Church Educational System require it to be supportive of these other BYUs, even as it must avoid the loss of its own mission by being homogenized from within. Quite a challenge! But you are equal to it, and your leaders in the BYU Board of Trustees and the Church Educational System are aware of it and will be your allies in resolving it.

As we think of BYU’s current mission, I like Commissioner Kim B. Clark’s nautical analogy. He wrote:

We often talk of BYU as the flagship of CES. And so it is. It is a remarkable institution. A flagship must be excellent in what it does, [but] it belongs to the battle group. Its areas of excellence are defined by the needs, mission, and purpose of the battle group. It is not a ship unto itself.

And, I might add, neither are the other ships in the battle group. Elder Clark continued his analogy:

A flagship university in CES must defer to the Lord, the Spirit, and the prophets of the Lord; make sure that its areas of excellence are aligned with the needs of the Church; and take action to use its expertise and its standing to build up, defend, and protect the Church. BYU is not just affiliated with the Church; it is an institution of the Church. It is the flagship of the Church’s system for education.14

Though a distinct and unique and precious institution in the Church Educational System, BYU will inevitably be affected by a new role for what Elder Clark called the battle group of CES. In November 2015, the Church Board of Trustees approved a new initiative for CES to provide “opportunities for education” for all Church members, wherever organized.15 Neither that initiative nor the more recent formation of BYU–Pathway Worldwide imply large increases in CES degree programs. But they do imply increases in overall CES enrollments as we pursue new initiatives to help members prepare for and access local educational opportunities and pursue them effectively, consistent with their needs and circumstances. That enhancement of “opportunities for education” for all Church members will necessarily draw upon the expertise and experience that is unique to Brigham Young University faculty and students.

Neal A. Maxwell made an important statement on this subject while he was Church commissioner of education:

Brigham Young University seeks to improve and “sanctify” itself for the sake of others—not for the praise of the world but to serve the world better.16

After citing this 1971 quotation from Commissioner Maxwell, in 2015 President Worthen added:

The final requirement, then, is to look for opportunities to share that information with others so that their lives can be better.17

I say, “Yes!”

I loved what President Worthen said last summer about the announcement of what was to be called BYU–Pathway Worldwide. He got it right, even that early in the game. Said he:

You will shortly hear from Elder Kim B. Clark about a new global initiative in the Church Educational System—an effort to provide learning to Saints and others throughout the world. This initiative is inspiring and will give us the opportunity to magnify the impact of what we do here. However, I believe we can best accomplish that by focusing on our principal and board-directed role, which is to enhance the learning experience of our students in all the ways described in the mission statement. We need not alter or change our focus; we simply need to do well—to do better—what we are already doing and then look for new ways to share.18

“New ways to share,” of course, contemplates some changes, notably in perspective, as befits the flagship in a fleet whose members must share and be aware of and supportive of the missions of each other and of the mission of the whole.

In my leadership conference message of August 2014, I encouraged BYU faculty to offer public, unassigned support of Church policies that others were challenging on secular grounds. Note that word unassigned. The Church should not have to ask or assign. The duty is inherent in the position.

In 2014 I quoted what our dear friend and associate Elder Neal A. Maxwell said to the BYU President’s Leadership Council just a few months before his death:

In a way LDS scholars at BYU and elsewhere are a little bit like the builders of the temple in Nauvoo, who worked with a trowel in one hand and a musket in the other. Today scholars building the temple of learning must also pause on occasion to defend the kingdom. I personally think this is one of the reasons the Lord established and maintains this university. The dual role of builder and defender is unique and ongoing. I am grateful we have scholars today who can handle, as it were, both trowels and muskets.19

I added then and I add now that

I would like to hear a little more musket fire from this temple of learning, especially on the subject of our fundamental doctrine and policies on the family. Since our members should be defenders of marriage as the union of a man and a woman, as Elder Nelson taught in his [2014] BYU commencement address, we should also expect our teachers to be outspoken on that subject.20

Here is another difficult question. This concerns another aspect of BYU assistance to various subjects of interest to the Church. Three years ago I said:

The Church needs the help of BYU faculty in a variety of ways. If the time required to give that help is not credited appropriately in department and college faculty evaluations for compensation and promotion, it will not be good for [departments, colleges, or] the university [as a whole].21

I am informed that you have made progress on this subject in the last few years but that more needs to be done in some colleges. I urge those of you who need further encouragement to reform the content and sophistication of your efforts in the unique circumstances of this university and to consider this my official encouragement to do so.

Closely related to that subject is an even greater need. As we seek to improve our efforts in the various colleges and departments of the university, and as we seek to help CES with similar needs in its various institutions and programs, the problem of how and what we measure is vital. What we measure will profoundly affect what we emphasize. There is great wisdom in the clever observation that the Saints do what they are inspected to do.

As I was preparing this talk, I was reading President John S. Tanner’s messages from when he was academic vice president at BYU. I was impressed with this insight:

What do we know about student learning at BYU? The short answer for our accreditors was obviously “not enough.” . . .

My deepest fear regarding assessment is that faculty will tailor objectives to measures rather than the other way around. That is, that we will define learning outcomes based on what is easy to measure. This would be a huge mistake because there is often an inverse correlation between what is easy to measure and what is important.22

This wisdom is related to President Boyd K. Packer’s frequent teaching that “what we can’t count is usually more important than what we can count.” In our Church culture of counting and reporting, I found that teaching challenging, but I did find a way to apply it to sacrament meeting, where we faithfully count attendance but have no way of counting the more important subject of how many really renew their covenants in partaking of the sacrament. My continued struggles with that teaching were helped in a stake conference of the Magna Utah South Stake many years ago. After I shared President Packer’s teaching, a woman gave me this quote: “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.”23 I concluded that if Boyd K. Packer and social scientists were teaching the same principle, it was time I took it seriously. I urge you to take this adaptation to heart and think about its application to the evaluation of student learning and faculty research and publication.

I conclude with a different question, focused on the central mission of Brigham Young University: How do we balance teaching and research in our predominantly undergraduate university that has significant faculty capacities and desires for research?

I acknowledge at the outset that the subject of research has many definitions and manifestations in different colleges, departments, and disciplines at BYU. These include large differences in the subject matters of research, in the opportunities for publication, and in the problem of how to evaluate different manifestations of research and publication for purposes of faculty status and promotion. I will have little to say about these complexities and diversities but will try to confine myself to principles and generalities that may be useful for administrators who must wrestle with the details.

I begin by quoting some thoughts President John S. Tanner shared here at BYU when he was the academic vice president. He began by quoting these familiar words from President Spencer W. Kimball’s 1967 address “Education for Eternity”:

In our world, there have risen brilliant stars in drama, music, literature, sculpture, painting, science, and all the graces. For long years I have had a vision of the BYU greatly increasing its already strong position of excellence till the eyes of all the world will be upon us.24

After quoting President Kimball from his 1967 BYU talk, President Tanner said:

President Kimball’s words were so audacious as to seem almost unbelievable. . . .

As I reread “Education for Eternity” and the now-familiar charge to become a “refining host” for “brilliant stars,” it struck me that President Kimball was thinking primarily about the accomplishments of BYU students, not faculty. . . .

This fact can serve as a salutary reminder for us about the fundamental purpose of scholarship at BYU. It is not, and must never be, to satisfy our own vainglory nor to advance our own careers. Nor even is it solely to advance truth and knowledge, though this is a worthy purpose and one specifically endorsed by BYU’s institutional objectives. The primary purpose for the Church’s large investment in faculty scholarship and creative work at BYU is to enable us to be a refining host for our students. Hence, we must strive for excellence, as President Kimball said, “not in arrogance or pride but in the spirit of service.”25

It is this concentration on our students that is the key to how we judge research at BYU. President Worthen explained it well to me in a recent memo:

For us (at least for me), [research] is an extension of our teaching mission. We do value top-flight research, but not exclusively—nor even primarily—for the discoveries that may result. We value it for the impact it can have on students, both in the way it enhances our teaching and the more direct impact it can have on students’ lives if we involve them in that research. In that respect, research (“among both faculty and students,” as the mission statement puts it), is, in my mind, just an extension of our teaching role.26

I agree that the kind of research we want at BYU is the kind that benefits our undergraduate students, directly through involving them and indirectly through improving our formal and informal teaching of them. We are not a research institute or a sponsor of discoveries that are primarily motivated to enhance the reputation of the university or its faculty. This does not devalue research but puts it in the context of our mission.

Here I divert into some semi-serious characterizations of this principle that are doubtless familiar to some of you. Some who are oriented to the academic world’s view of research may say, “No other success in teaching can compensate for failure in research.”27 Some who are oriented to BYU’s mission may reply, “No other success in research can compensate for failure in teaching.” If you think these questions do not apply to all colleges in the university, I offer the following application in the college of religion: “Faith without works is dead.”28 But I reply, “Works without faith is even deader.”

Let us return to the serious and persuasive words of President Worthen, speaking of one aspect of this question in light of the scriptural caution:

“Because their hearts are set so much upon the things of this world, and aspire to the honors of men” [D&C 121:35]. In the academy in particular, there will always be a pull for us to become like others. The prestige lies in doing research that may not be exactly the way we would do it if there were not outside peer pressure. There is pressure to emphasize research more than teaching, to ignore undergraduates. One of the things we need to be constantly concerned about is that our hearts don’t get set so much on the things of this world and aspire to the honors of men that we start to drift internally.29

In your 2016 BYU university conference, President Worthen said this:

Similarly, as important as our research may be—and some of it is of enormous importance, some of it life-changing, even lifesaving—it is, in the long run, not as important as the eternal development of our students. I applaud and admire the way so many of you pursue both these ends with full purpose of heart and mind, without sacrificing either. But it is hard work.30

And, I might add, it is extremely difficult and expensive to sustain these dual priorities over time. Most will conclude that it is more effective and more sustainable to pursue the kind of research President Worthen has defined—part of the teaching mission of the university.

© 2017 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Notes

1. Dallin H. Oaks, “It Hasn’t Been Easy and It Won’t Get Easier,” BYU leadership conference, 25 August 2014.

2. Kevin J Worthen, “Two Challenges Facing Brigham Young University as a Religiously Affiliated University,” BYU Studies Quarterly 54, no. 2 (2015): 8; quoting Robert John Araujo, “‘The Harvest Is Plentiful, but the Laborers Are Few’: Hiring Practices and Religiously Affiliated Universities,” University of Richmond Law Review 30, no. 3 (May 1996): 718. Araujo was referencing Mark Tushnet, “Catholic Legal Education at a National Law School: Reflections on the Georgetown Experience,” in William C. McFadden, ed., Georgetown at Two Hundred: Faculty Reflections on the University’s Future (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1990), 322.

3. See David Brooks, “The Cultural Value of Christian Higher Education,” keynote speech given at the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities 40th Anniversary Celebration Gala, Washington, DC, 27 January 2016; published in Advance 7, no. 1 (spring 2016): 47–52.

4. Brooks, “Cultural Value,” 47.

5. Brooks, “Cultural Value,” 48.

6. Brooks, “Cultural Value,” 48–49, 52.

7. Brooks, “Cultural Value,” 48.

8. Kevin J Worthen, “The Why of the Y,” BYU annual university conference address, 26 August 2014.

9. Worthen, “The Why of the Y”; quoting from The Mission of Brigham Young University and The Aims of a BYU Education (Provo: BYU, 2014), 1–2.

10. Worthen, “The Why of the Y”; quoting from Spencer W. Kimball, “Education for Eternity,” pre-school address to BYU faculty and staff, 12 September 1967, 11.

11. Russell M. Nelson, “Controlled Growth,” BYU leadership meeting, 25 August 2014.

13. Kevin J Worthen, “A Vibrant and Determined Community of Learners and Lifters,” BYU annual university conference, 24 August 2015.

14. Kim B. Clark, memo to Dallin H. Oaks, 12 April 2017.

15. Kim B. Clark, “The CES Global Education Initiative: The Lord’s System for Education in His Church,” Seminaries and Institutes of Religion annual training broadcast, 14 June 2016, lds.org/broadcasts/article/satellite-training-broadcast/2016/06/the-ces-global-education-initiative-the

-lords-system-for-education-in-his-church?lang=eng. See also Neal Buckles, “Three-Semester Pathway Program Changes Name to PathwayConnect,” PathwayConnect newsroom, pathwaynewsroom.org/three-semester-pathway-program-changes-name-to-pathwayconnect.

16. Neal A. Maxwell, “Greetings to the President,” Addresses Delivered at the Inauguration of Dallin Harris Oaks, 12 November 1971 (Provo: BYU Press, 1971), 1; quoted in Spencer W. Kimball, “The Second Century of Brigham Young University,” BYU devotional address, 10 October 1975.

17. Worthen, “Vibrant and Determined.”

18. Kevin J Worthen, “Inspiring Learning,” BYU university conference address, 22 August 2016.

19. Neal A. Maxwell, “Blending Research and Revelation,” remarks at the BYU President’s Leadership Council meetings, 19 March 2004; quoted in Oaks, “It Hasn’t Been Easy.”

20. Oaks, “It Hasn’t Been Easy”; emphasis in original; referring to Russell M. Nelson, “Disciples of Jesus Christ—Defenders of Marriage,” BYU commencement address, 14 August 2014.

21. Oaks, “It Hasn’t Been Easy.”

22. John S. Tanner, “Building a Better House of Learning,” BYU annual university conference faculty session address, 29 August 2006.

23. William Bruce Cameron, Informal Sociology: A Casual Introduction to Sociological Thinking (New York: Random House, 1963), 13.

24. Kimball, “Education for Eternity,” 12; quoted in John S. Tanner, “A House of Dreams,” BYU annual university conference faculty session address, 28 August 2007. Spencer W. Kimball similarly used this in both Kimball, “Second Century,” and Spencer W. Kimball, “Installation of and Charge to the President,” Inaugural Addresses, 14 November 1980, Brigham Young University, 9.

25. Tanner, “A House of Dreams”; quoting from both Kimball, “Education for Eternity,” 12, and from Kimball, “Second Century.”

26. Kevin J Worthen, memo to Dallin H. Oaks, 12 April 2017; quoting Mission and Aims, 2.

27. Compare: “No other success can compensate for failure in the home” (James Edward McCulloch, Home: The Savior of Civilization [Washington, DC: Southern Co-operative League, 1924], 42); quoted by David O. McKay, CR, April 1935, 116.

28. James 2:20.

29. Worthen, “Two Challenges,” 9.

30. Worthen, “Inspiring Learning.”

Dallin H. Oaks, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, delivered this BYU leadership conference address on April 21, 2017.