I begin by expressing gratitude to the hundreds of friends who have prayed or sent messages of concern for my wife, June, who was the first lady of BYU for nine years ending in 1980. She was a great lover of BYU and its people and all its efforts. These prayers and messages were strengthening to her and to me. Many have asked how I am getting along since her death just over a month ago. I always answer, “As well as can be expected.” Thank you, dear friends.

Your conference theme is “Neglect Not the Gift That Is in Thee.” One of the gifts that is in all of the workers of BYU stems from the difference between employment at BYU and employment at any other college or university outside the Church Educational System. I wish to speak about that gift—that difference—with special emphasis on the subject of service at BYU. I do so by wisdom and not by commandment (see D&C 28:5). What I have to say is based on my experience in law, in higher education, in Church education, and in the leading councils of the Church, but I am not assigned to speak by way of commandment.

My message can be summarized in one paragraph. BYU faculty and staff have a contract relationship with their corporate employer and a covenant relationship with its sponsoring Church. This twofold relationship of both contract and covenant puts BYU employees in a position that is uniquely different from the employees of other colleges and universities outside the Church Educational System. It also puts BYU employees in a unique position by comparison with Church members who do not have a contract relationship with a Church entity. The rest of my message will discuss some of the implications of these unique positions. Applying them to the subject of service at BYU, I will urge you to neglect not the unique gift of your difference from others.

Because you have a contract relationship, you are compensated and you are subject to laws and regulations and contractual responsibilities and consequences that do not apply to Church members generally. You have employment duties and you are subject to employer authorities not applicable to other members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Even more important, because BYU employees-members have a covenant relationship with the Church that owns and controls BYU, you also have covenant obligations beyond your contract obligations. (I will describe the special position of non-LDS employees of BYU later.) The interplay of these two relationships on your service at BYU is the subject of my talk.

The fact that the BYU worker’s position is different is not understood or accepted by some interested observers—and even by some of our own faculty, staff, and students. This is evident from what some choose to do or choose to say. I will not give examples but only ask you to supply your own as my message procee

I

Service at BYU is different from other colleges and universities because BYU is owned and controlled by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which has commissioned BYU to accomplish a special kind of teaching. To some extent that teaching is like the teaching done by other colleges and universities. This tempts us to conclude that BYU is no different from the others. In contrast, to some extent the teaching done by BYU is like the teaching done by called servants of the Lord, including general and local authorities, missionaries, and teachers. That has caused some critics to charge that BYU teaching is like Sunday School teaching. Both conclusions are wrong. Both overlook the dual character of BYU’s mission. Both ignore the complexity of the assignment to accomplish a twofold task with workers who have dual responsibilities, one undertaken by contract and the other by covenant.

Here I pause to cite some authorities on my conclusion that BYU is different. Consider these words by one who knew:

It has been said the Saints will be saviors upon Mount Zion, that they are destined to redeem the world. Redeem the world from what? From the thralldom of sin, ignorance, and degradation! In order to do this, Zion will have to take the lead in everything and consequently also in education. . . .

A glance over the conditions of mankind in this our day with its misery, discontent, and corruption, and disintegration of the social, religious, and philosophic fabrics, shows that this generation has been put into the balance and has been found wanting. A following, therefore, in the old grooves, would simply lead to the same results, and that is what the Lord has designed shall be avoided in Zion. President Brigham Young felt it in his heart that an educational system ought to be inaugurated in Zion in which, as he put it in his terse way of saying things, neither the alphabet nor the multiplication table should be taught without the Spirit of God.

Thus was started this nucleus of a new system. [Karl G. Maeser, “History of the Academy,” in Educating Zion, eds. John W. Welch and Don E. Norton [Provo: BYU Studies, 1996], p. 2]

Those words were spoken in 1891 by President Karl G. Maeser at Brigham Young Academy’s first Founders Day exercises.

A more modern statement of BYU’s uniqueness is this familiar declaration by President Spencer W. Kimball:

The uniqueness of Brigham Young University lies in its special role—education for eternity—which it must carry in addition to the usual tasks of a university. This means concern—curricular and behavioral—not only for the “whole man,” but also for the “eternal man.” Where all universities seek to preserve the heritage of knowledge that history has washed to their feet, this faculty has a double heritage—the preserving of knowledge of men and the revealed truths sent from heaven.

While all universities seek to push back the frontiers of knowledge further and further, this faculty must do that and also keep new knowledge in perspective, so that the avalanche of facts does not carry away saving, exalting truths from the value systems of our youth. [Spencer W. Kimball, “Education for Eternity,” reprinted in “Climbing the Hills Just Ahead: Three Addresses,” Educating Zion, pp. 43–44]

Highly relevant to this subject is Paul’s plea, quoted in your conference theme, that we “neglect not the gift that is in [us]” (1 Timothy 4:14). Also relevant to our circumstances are these words of the apostle Paul written to Timothy just a few verses before the direction that is your theme:

For therefore we both labour and suffer reproach, because we trust in the living God, who is the Saviour of all men, specially of those that believe.

These things command and teach. [1 Timothy 4:10–11]

As President Kimball taught, BYU’s responsibility to educate for eternity requires a curricular and behavioral concern for the things of eternity as well as the things of mortality. This concern for revealed truth as well as earthly knowledge requires a concern for our students’ personal values and conduct as well as their academic achievements. As other colleges and universities have abandoned or substantially weakened their behavioral concerns, our Church Educational System institutions have come to stand almost alone on this matter. In Paul’s words, because we “trust in the living God” in seeking to carry out our dual teaching assignment, “we both labour and suffer reproach,” but we consider ourselves under covenant to “command and teach” these things.

The unique twofold teaching responsibility of Brigham Young University requires that it be concerned about the personal conduct of its employees, especially its teachers. In the contractual relationship that concern is reflected through the requirement of temple recommend worthiness as an expectation of employment. But it is reflected even more importantly through the covenant relationship member-employees have with the Church, which sponsors BYU. Church members are under covenant to serve one another. For every employee of Brigham Young University the primary opportunity for covenant service is through their BYU employment, and their covenant responsibilities for service exceed their contractual responsibilities.

President Kimball described one important aspect of our covenant obligations in these words:

It would be my hope that twenty thousand students might feel the normalcy and beauty of your lives. I hope you will each qualify for the students’ admiration and affection. It is my hope that these youth will have abundant lives, beautiful family patterns, after the ideal of an eternal family, with you for their example. . . .

I would like these youth to see their instructors in community life as dignified, happy cooperators; in Church life as devout, dependable, efficient leaders; and in personal life honorable, full of integrity; and as President John Taylor said, “Let us live so . . . that angels can minister to us and the Holy Ghost dwell with us.” [“Education for Eternity,” in “Climbing the Hills,” Educating Zion, pp. 50–51]

University employees who are not members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints do not have a covenant relationship with the Church. However, they are contractual employees of a university that has a particular mission. They contract by employment to further and not to detract from that mission. For these employees the contract is sufficient, and as a group they have been remarkably true to their responsibilities.

II

Having stated some general principles of your dual relationship to BYU and to its sponsoring Church, I now wish to discuss some of the ways these principles affect your responsibilities of service at BYU.

After I was called to the Quorum of the Twelve, I gave my first address in general conference in October 1984. I reflected on the significance of my calling and the callings of others. I addressed the subject of why we serve. This evening I have concluded to repeat some of the ideas I felt impressed to share at that time, to enlarge them to include a few thoughts about contract as well as covenant service, and to apply these ideas to the specific subject of service at BYU.

Service is an imperative for those who worship Jesus Christ and a covenant obligation of those who belong to his Church. To followers who were vying for prominent positions in his kingdom, the Savior taught, “Whosoever will be chief among you, let him be your servant” (Matthew 20:27). In latter-day revelation the Lord has commanded that we “succor the weak, lift up the hands which hang down, and strengthen the feeble knees” (D&C 81:5). Alma’s great teaching about qualifications for baptism and the effect of the baptismal covenant refers to willingness “to bear one another’s burdens” (Mosiah 18:8) and “a covenant with him, that ye will serve him and keep his commandments” (Mosiah 18:10). Holders of the Melchizedek Priesthood receive it upon a covenant to use its powers in the service of others. Truly, all members of the Church of Jesus Christ have a covenant obligation of service to others.

Whether our service is to our fellowmen or to God, it is the same (see Mosiah 2:17). If we love him, we should keep his commandments and feed his sheep (see John 21:16–17).

When we think of service, we usually think of the acts of our hands. But the scriptures teach that the Lord looks to our thoughts as well as to our acts. One of God’s earliest commandments to Israel was to love him and “serve him with all your heart and with all your soul” (Deuteronomy 11:13). Latter-day revelation declares that the Lord requires not only the acts of the children of men, but “the Lord requireth the heart and a willing mind” (D&C 64:34). Similarly, the prophet Alma taught that if we have hardened our hearts against the word of God, we will “not dare to look up to our God” at the final judgment because “all our works will condemn us . . . ; and our thoughts will also condemn us” (Alma 12:14).

In these latter days we are commanded to “seek to bring forth and establish the cause of Zion” (D&C 6:6). Unfortunately, not all who accomplish works under that heading are really intending to build up Zion or strengthen the faith of the people of God. Other motives can be at work.

These scriptures make clear that in order to purify our service it is necessary to consider not only how we serve but also why we serve. For BYU workers that inquiry is complicated by the dual relationship I have described. Consequently, it will be desirable to consider both why we serve under contract and why we serve under covenant.

People serve one another for different reasons, and some reasons are better than others. None of us serves in every capacity all the time for only a single reason. Since we are imperfect beings, most of us probably serve for a combination of reasons, and the combinations may be different from time to time as we grow spiritually. But we should all strive to serve for the reasons that are highest and best.

Why do we serve? By way of illustration, and without pretending to be exhaustive, I will suggest six different reasons for service. I will discuss these in ascending order from the lesser to the greater.

1. For Riches or Honor

Some serve others for hope of earthly reward. Such a man or woman might serve their fellowmen in an effort to increase income, to aid in acquiring wealth, or to achieve prominence or obtain worldly honors. If you are thinking of your contractual relationship to BYU, you may be saying, “What’s wrong with serving for income or other personal advantage?” And I would say, “Nothing,” so far as contractual responsibilities are concerned. But covenant service is another thing. It is ironic that the first reason for contract service is the least worthy reason for Church or covenant service. The scriptures teach this.

Service that is ostensibly unselfish but is really for the sake of riches or honor clearly comes within the Book of Mormon definition of priestcraft, which is to “preach” or serve “that they may get gain and praise of the world; but they seek not the welfare of Zion” (2 Nephi 26:29). Such service surely comes within the Savior’s condemnation of those who “outwardly appear righteous unto men, but within . . . are full of hypocrisy and iniquity” (Matthew 23:28). Such service earns no gospel reward.

So what is a BYU employee to do in respect to gospel service? Obviously, we accept and serve in our Church callings. But what about the majority of our time that is spent in employment activities?

I suggest that in addition to fulfilling their contractual obligations, BYU workers are obliged by their gospel covenants to engage in personal activities and to use their personal influence to preserve the spirit of gospel service. Speaking here in 1975, then Elder Gordon B. Hinckley said this:

Service to mankind must ever be the ideal of this great university. It was established in the name of Jesus Christ, who gave his life that all men might live. It was founded and built and helped through its early years of struggle by men whose faith was more precious than life and whose concern for others was above concern for self. If we ever lose that spirit, we have lost everything. [Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Second Hundred Years: A New Level of Achievement,” inAnnual University Conference 1975, Brigham Young University, p. 56]

What does this mean in practice? It surely does not mean that we cannot be compensated in our contractual relationship. But it does mean that we should not act solely for compensation or seek compensation for everything we do in an employment relationship. If we do not go beyond our contractual duties and extend and magnify our efforts as a matter of gospel service, we will neglect the gift (the unique position we occupy) that is in us. We must never lose that “concern for others . . . above concern for self” that President Hinckley described as the “spirit” we must retain, or we will cease to be worthy of his description of BYU as “the university of the Church of Jesus Christ” (Annual University Conference 1975, p. 52). Those who succeed at covenant service may yet experience the irony of enjoying eternal advantage from the inadequacy of earthly compensation for all they have done.

Here I insert a footnote. After I wrote the words I have just spoken I had an impression that I had spoken of this subject once before. I found that I had. Eighteen years ago this month I gave a commencement address just as I was leaving my service at BYU. My subject was “Challenges to BYU in the Eighties,” and one of those challenges was the subject of BYU compensation. Though I did not use the terms I now use to contrast contract service and covenant service, I did speak of that contrast:

I have also been very uneasy about trying to match other universities on a dollar-for-dollar basis in the salaries paid at BYU. We have a unique sponsorship and a sacred mission. Each of us should feel a special relationship with our sponsoring Church, our Board of Trustees, and the sacred mission we have to teach the gospel of Jesus Christ as well as our professional subjects. Generations have taught at BYU for less than they could have been paid in other employment, and we stand on the foundations laid through their sacrifices. Those foundations of Church sponsorship, spiritual mission, and personal sacrifice are essential to what sets us apart and makes us worthy to survive. As we strive for excellence in terms recognizable in the world of scholarship, we must not lose touch with the spiritual endowment that qualifies us for leadership.

I wish I had a formula for balancing the countervailing pressures of market and sacrifice. We must not lose the spirit of sacrifice in employment at Brigham Young University, but neither must that sacrifice be exploited or become an excuse for unrealistic compensation policies in the university. After nine years of worrying over this problem, I have now left it behind for President Holland as one of the problems I have been unable to solve or ameliorate. I suspect that the only feasible solution is to be explicit about the issue, but to leave it to be balanced and resolved in the hearts and minds of individual faculty members and administrators. [Dallin H. Oaks, “Challenges to BYU in the Eighties,” BYU commencement address, 18 August 1980, in The Bond of Charity: BYU August 1980 Addresses, p. 35]

2. To Obtain Good Companionship

Another reason for service—probably more worthy than the first in gospel terms but still in the category of service in search of earthly reward—is that motivated by a personal desire to obtain good companionship. We surely have good associations in our Church service, but is that why we serve?

Persons who serve only to obtain good companionship are more selective in choosing their friends than the Master was in choosing his servants or associates. Jesus called most of his servants from those in humble circumstances. And he associated with sinners. He answered critics of such association by saying, “They that are whole need not a physician; but they that are sick. I came not to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance” (Luke 5:31–32).

As applied to gospel service, these first two reasons for service are selfish and self-centered and unworthy of Saints. As the apostle Paul said, we who are strong enough to bear the infirmities of the weak should not do so “to please ourselves” (Romans 15:1). Reasons aimed at earthly rewards for gospel service are distinctly lesser in character and reward than the other reasons I will discuss.

3. Fear of Punishment

Some may serve out of fear of eternal punishment. The scriptures abound with descriptions of the miserable state of those who fail to follow the commandments of God. Thus, King Benjamin taught his people that the soul of the unrepentant transgressor would be filled with

a lively sense of his own guilt, which doth cause him to shrink from the presence of the Lord, and doth fill his breast with guilt, and pain, and anguish, which is like an unquenchable fire, whose flame ascendeth up forever and ever. [Mosiah 2:38]

Such descriptions surely offer sufficient incentive for keeping the commandment of service. But service out of fear of eternal punishment is a lesser motive at best.

4. Duty or Loyalty

Other persons may serve out of a sense of duty or out of loyalty to friends or family or traditions. These are those I would call the good soldiers, who instinctively do what they are asked in gospel service without question and sometimes without giving much thought to the reasons for their service. Such persons fill the ranks of voluntary organizations everywhere, and they do much good. I am sure they are blessed and loved of God. “Every man according as he purposeth in his heart, so let him give; not grudgingly, or of necessity: for God loveth a cheerful giver” (2 Corinthians 9:7). We have all benefited by the good works of persons who serve out of a sense of duty or loyalty to various wholesome causes. These are the good and honorable men and women of the earth.

5. Hope of an Eternal Reward

Although those who serve out of fear of punishment or out of a sense of duty undoubtedly qualify for the blessings of heaven, there are still higher reasons for service.

One such higher reason for covenant service is the hope of an eternal reward. By “covenant service” I mean service beyond what we are required to do by contract, and by “eternal reward” I mean rewards beyond the compensation we receive for contract service. Hope of an eternal reward is one of the most powerful sources of motivation for gospel service. For example, I believe it is a significant motivation for the unending service we give to one another in our families. As a reason for service, this motivation necessarily involves faith in God and in the fulfillment of his prophecies. The scriptures are rich in promises of eternal rewards. For example, in a revelation given through the Prophet Joseph Smith in June 1829, the Lord said, “If you keep my commandments and endure to the end you shall have eternal life, which gift is the greatest of all the gifts of God” (D&C 14:7).

6. The Highest Motive for Service

The last motive I will discuss is, in my opinion, the highest reason of all. In its relationship to covenant service, it is what the scriptures call “a more excellent way” (1 Corinthians 12:31).

“Charity is the pure love of Christ” (Moroni 7:47). The scriptures teach that this virtue is “the greatest of all” (Moroni 7:46). The apostle Paul wrote:

Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. . . .

And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor . . . , and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing. [1 Corinthians 13:1–3]

We know from these inspired words that even the most extreme acts of service profit us nothing unless motivated by the pure love of Christ. If our gospel service is to be most efficacious, it must be accomplished for the love of God and the love of his children. The Savior illustrated that principle in the Sermon on the Mount, where he commanded us to love our enemies, bless them that curse us, do good to them that hate us, and pray for them that despitefully use us and persecute us (see Matthew 5:44).

Service for the love of God and our fellowmen is surely a different kind of service than that prescribed by contract, where we receive value and give equivalent value in return. The Savior explained that difference in this same teaching when he said, “For if ye love them which love you, what reward have ye?” (Matthew 5:46). Similarly, as he continued his Sermon on the Mount, he declared:

Take heed that ye do not your alms before men, to be seen of them: otherwise ye have no reward of your Father which is in heaven.

Therefore when thou doest thine alms, do not sound a trumpet before thee, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, that they may have glory of men. Verily I say unto you, They have their reward. [Matthew 6:1–2]

This principle—that our gospel service should be for the love of God and the love of fellowmen rather than for personal advantage or any other lesser motive—is admittedly a high standard. The Savior must have seen it so, since he joined his commandment for selfless and complete love directly with the ideal of perfection. Immediately after commanding that our covenant service include loving our enemies, he gave this great commandment: “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect” (Matthew 5:48).

This principle of service is reaffirmed in section 4 of the Doctrine and Covenants:

Therefore, O ye that embark in the service of God, see that ye serve him with all your heart, might, mind and strength, that ye may stand blameless before God at the last day. [D&C 4:2]

Service with all of our heart and mind, which goes far beyond service with all of our might and strength, is a high challenge for all of us. It goes far beyond the quid pro quo of contract service. It is unique to our service by covenant. It is free of selfish ambition. It is motivated only by the pure love of God and our fellowmen.

If we have difficulty with the command that we serve for love, a Book of Mormon teaching can help us. After describing the importance of charity, the prophet Moroni counseled:

Wherefore, my beloved brethren, pray unto the Father with all the energy of heart, that ye may be filled with this love, which he hath bestowed upon all who are true followers of his Son, Jesus Christ. [Moroni 7:48]

I testify that God expects us to work to purify our hearts and our thoughts so that we may serve one another for the highest and best reason, the pure love of Christ.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

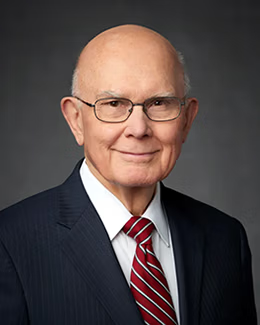

Dallin H. Oaks was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this Sunday evening fireside address was delivered at the BYU Annual University Conference on 23 August 1998.