My dear brothers and sisters, I am glad to participate in this BYU Campus Education Week.

This year’s theme, “Education: Refined by Reason and Revelation,” is both appropriate and challenging. The idea that education should be based on both reason and revelation is a true gospel principle. It is rooted in the divine direction that we “seek learning, even by study and also by faith” (D&C 88:118). It is an immensely important principle that some good persons do not understand and apply. Some who have refined their application of reason reject revelation, and some who understand revelation seem to misunderstand its relationship with reason.

We can be edified by the example of great Latter-day Saints who honor and apply both reason and revelation. Arthur Henry King, a distinguished British civil servant who became a professor at BYU and then president of the London Temple, is such an individual. I quote from his book The Abundance of the Heart (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1986):

Conversion is not a matter of choosing what we like and ignoring the rest, but of whole-minded acceptance. . . . When we have performed this act of faith, . . . all the difficulties are resolved by it. When we have laid down at Christ’s feet all our scholarship, all our learning, all the tools of our trades, we discover that we may pick them all up again, clean them, adjust them, and use them for the Church in the name of Christ and in the light of his countenance. We do not need to discard them. All we need to do is to use them from the faith which now possesses us. And we find that we can. [p. 30]

Those words are both a challenge for all of us and an appropriate introduction for my subject today.

I

In this devotional message I wish to reason about a basic principle given in modern revelation but not as well understood or applied as it should be. This principle was given to guide us in our relationships with one another. It is especially important for parents with teenage children.

Three verses of the Doctrine and Covenants identify an important contrast between sins and mistakes. I had never noticed these verses until about one year ago, when I was reading the Doctrine and Covenants for the fifteenth or twentieth time. Their direction came to my mind with such freshness and impact that I thought they might have been newly inserted in my book. That is the way with prayerful study of the scriptures. The scriptures do not change, but we do, and so the old scriptures can give us new insights every time we read them.

The twentieth section of the Doctrine and Covenants, given the same month the Church was organized, is the basic revelation on Church government. It contains one verse giving this important direction: “Any member of the church of Christ transgressing, or being overtaken in a fault, shall be dealt with as the scriptures direct” (D&C 20:80). The clear implication of this verse is that transgressing is different from being overtaken in a fault, but that either type of action is to be dealt with as the scriptures direct.

The scriptures contain various directions for dealing with members, but the key direction for present purposes is contained in two verses in the November 1831 revelation given as the preface to the book that is now the Doctrine and Covenants. These verses follow the Lord’s explanation that he has given his servants the commandments in that book “after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding” (D&C 1:24). Succeeding verses clarify the difference between error and sin, and give distinctly different directions for the correction of each. I quote verses 25 and 27:

And inasmuch as they erred it might be made known. . . .

And inasmuch as they sinned they might be chastened, that they might repent. [D&C 1:25, 27]

Under these verses transgressing is different from being at fault, and to err is different than to sin. Here I need to define some terms. I believe that in these scriptures sin and transgression mean the same thing. Similarly, to err or to be at fault are also equivalent. In referring to this second category, I will use the more familiar description: “to make a mistake.”

The subject of this talk is the contrast between sins and mistakes. Both can hurt us and both require attention, but the scriptures direct a different treatment. Chewing on a live electrical cord or diving headfirst into water of uncertain depth are mistakes that should be made known so they can be corrected. Violations of the commandments of God are sins that require chastening and repentance. In the treatment process we should not require repentance for mistakes, but we are commanded to preach the necessity of repentance for sins.

That is my message. The rest of this talk is just for purposes of illustration and application.

II

My first illustration uses words I learned as a young boy reading the Sears Roebuck catalog. In those days, each item of merchandise in the catalog was offered in three different qualities: good, better, and best. Sears didn’t use the word bad, but if I add that word I have four words that permit me to illustrate my first point with clarity. For most of us, most of the time, the choice between good and bad is easy. What usually causes us difficulty is determining which uses of our time and influence are merely good, or better, or best. Applying that fact to the question of sins and mistakes, I would say that a wrong choice in the contest between what is good and what is bad is a sin, but a poor choice among things that are good, better, and best is merely a mistake.

Mortals make those kinds of mistakes all the time. We can read of some of them in Church history. I believe some of the persecutions our forefathers endured were a result of their sins. The Lord told them so by revelation (see D&C 101:2). I believe some of their persecutions were also the result of mistakes. Thus, Sidney Rigdon’s defiant “salt sermon,” which contributed to conditions that brought about the Saints’ expulsion from Missouri, was probably a mistake. Similarly, some mistaken decisions on Kirtland banking policies plagued the Saints for more than a decade. These financial difficulties were perhaps portended in the Lord’s warning to the Prophet Joseph Smith: “And in temporal labors thou shalt not have strength, for this is not thy calling” (D&C 24:9).

On a more personal level, consider the mistake described by Truman G. Madsen in his fine book Joseph Smith the Prophet (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1989):

In a relaxed moment one day the Prophet turned to his secretary, Howard Coray, and said, “Brother Coray I wish you were a little larger. I would like to have some fun with you,” meaning wrestling. Brother Coray said, “Perhaps you can as it is.” The Prophet reached and grappled him and twisted him over—and broke his leg. All compassion, he carried him home, put him in bed, and splinted and bandaged his leg. [p. 31]

In teaching the Saints not to accuse one another, the Prophet Joseph Smith said, “What many people call sin is not sin” (Teachings, p. 193). I believe the large category of actions that are mistakes rather than sins illustrates the truth of that statement. If we would be more understanding of one another’s mistakes, being satisfied merely to correct and not to chasten or call to repentance, we would surely promote loving and living together in greater peace and harmony.

The appropriateness of that approach as applied to mistakes is surely illustrated by the Prophet Joseph Smith’s well-known teachings to the first Relief Society. There he taught the sisters to be kind and loving toward those who made mistakes, and also toward sinners. He said:

Suppose that Jesus Christ and holy angels should object to us on frivolous things, what would become of us? We must be merciful to one another, and overlook small things. . . .

Nothing is so much calculated to lead people to forsake sin as to take them by the hand, and watch over them with tenderness. When persons manifest the least kindness and love to me, O what power it has over my mind, while the opposite course has a tendency to harrow up all the harsh feelings and depress the human mind. . . .

. . . There should be no license for sin, but mercy should go hand in hand with reproof. [Teachings, pp. 240–41]

The book of Proverbs is filled with advice on mistakes or errors, and the word most frequently applied to the person who fails to behave appropriately in these areas is fool. Our dictionary defines a fool as a person lacking in judgment or prudence. A fool is a fool, not a sinner. Our English writers understood that difference, and used it in their frequent contrast of fools and knaves.

Proverbs says that “A fool uttereth all his mind: but a wise man keepeth it in till afterwards” (Proverbs 29:11). The Old Testament’s usage of the word fool is evident in Saul’s confession: “I have played the fool, and have erred exceedingly” (1 Samuel 26:21). Stimulated by that expression, an English playwright penned these lines, which remind us of mortality’s abundant field for foolish conduct.

When we play the fool, how wide

The theater expands! beside,

How long the audience sits before us!

How many prompters! what a chorus!

[Walter Savage Landor, Plays (1846), stanza 2]

The Savior used the term fool to characterize the lesson in his parable about the rich man who built greater barns to store his abundant fruits and goods and then said to his soul, “Soul, thou hast much goods laid up for many years; take thine ease, eat, drink, and be merry” (Luke 12:19). Then, the Savior taught,

God said unto him, Thou fool, this night thy soul shall be required of thee: then whose shall those things be, which thou hast provided?

So is he that layeth up treasure for himself, and is not rich toward God. [Luke 12:20–21]

The distinction between sins and mistakes is important in our actions in the realm of politics and public-policy debates. We have seen some very bitter finger-pointing among Latter-day Saints who disagree with one another on the policies our government should follow, the political parties we should support, or the persons we should elect as our public servants. Such disagreements are inevitable in representative government. But it is not inevitable that disagreements would result in the personal denunciations and bitter feelings described in the press or encountered in personal conversations.

When we understand the difference between sins and mistakes, we realize that almost all of our disagreements in elections and public-policy debates are matters of error (mistake) rather than transgression (sin). The inspired direction for such differences of opinion is to try to correct the errors by pointing them out in civil discourse, but not to chasten or denounce as sinners those we think have committed the errors. (Of course, there are some public policies so intertwined with moral issues that there may be only one morally right position, but that is rare).

In a recent interview with the press, President Howard W. Hunter said that one of our objectives as a church is “to change the world and its thinking.” Identifying how we need to go about that task, President Hunter said, “We have an obligation, as Christians—as members of the Church—and we call upon all people to be more kind and more considerate—whether it be in our homes, in our businesses, in our relations in society.” Concluding this plea, he said that we have a responsibility to teach “a Christ-like response to all the problems of the world” (“Prophet Focuses on Christ’s Message,” Church News, 9 July 1994, p. 3). Understanding and applying the distinction between sins and mistakes will help us fulfill that divinely imposed responsibility.

The scriptures and our leaders have also taught us principles that require a loving approach to those with whom we have any kind of disagreement on matters of religious belief. In one of the great prophecies that concluded his ministry, the prophet Nephi described the false churches of the last days that would teach “false and vain and foolish doctrines” (2 Nephi 28:9). He denounced many of their followers for obvious wickedness, including robbing the poor and committing whoredoms. Then he referred to another group, an exceptional few who were the humble followers of Christ. Note the words he used to describe these two groups.

They have all gone astray save it be a few, who are the humble followers of Christ; nevertheless, they are led, that in many instances they do err because they are taught by the precepts of men. [2 Nephi 28:14]

Here we see that when humble followers of Christ are led astray by the precepts of men, their offense is error, not transgression.

Elder George A. Smith applied that principle in an address delivered in the Tabernacle in Salt Lake City in 1870. Referring to honest persons in the Christian world at the time of the Restoration who had been led astray as to doctrine, he used the word error and indicated that the Lord would be very merciful to them.

There were, however, honest persons in all of the denominations, and God has respect to every man who is honest of heart and purpose, though he may be deceived, and in error as to principle and doctrine; yet so far as that error is the result of their being deceived by the cunning craftiness of men, or of circumstances over which such have no control, the Lord in His abundant mercy looks with allowance thereon, and in His great economy He has provided different glories and ordained that all persons shall be judged according to the knowledge they possess and the use they make of that knowledge, and according to the deeds done in the body, whether good or evil. [JD 13:346]

Elder Smith’s explanation obviously relied on the doctrine that defines the degree of responsibility of persons who have not received the law. The apostle Paul taught that we sin only when we know the law (see Romans 7:7). In a clear elaboration of that principle, the prophet Jacob affirms that “where there is no law given . . . there is no condemnation” (2 Nephi 9:25). As a result, he taught, “the atonement satisfieth the demands of his justice upon all those who have not the law given to them” (2 Nephi 9:26; see also Alma 42:17). Similarly, the prophet Mormon declared “that all little children are alive in Christ, and also all they that are without the law. For the power of redemption cometh on all them that have no law” (Moroni 8:22). This is the principle another Book of Mormon prophet applied in teaching the wicked Nephites that unless they would repent, it would be better for the Lamanites than for them:

For behold, they are more righteous than you, for they have not sinned against that great knowledge which ye have received; therefore the Lord will be merciful unto them; . . . even when thou shalt be utterly destroyed except thou shalt repent. [Helaman 7:24]

Under this doctrine, persons who break a law that has not been given to them are not accountable for sins. Of course, all men have been given the Spirit of Christ (conscience) that they may “know good from evil” (2 Nephi 2:5, Moroni 7:16). This makes us all aware of the wrongfulness of certain conduct—such as taking a life or stealing—but it does not make men accountable for laws that need to be specifically taught, like the knowledge that had been received by the Nephites but not by the Lamanites (see Helaman 7:24). Persons who break those kinds of laws when they have not received them are guilty of mistakes that should be corrected, but they are not accountable for sins. They may suffer for their mistakes, just as a smoker suffers for breaking a law of health even if he has never heard of the Word of Wisdom. There are inherent penalties in errors or mistakes, but their perpetrators should not be branded as sinners.

We understand from our doctrine that before the age of accountability a child is “not capable of committing sin” (Moroni 8:8). During that time, children can commit mistakes, even very serious and damaging ones that must be corrected, but their acts are not accountable as sins.

Even after children reach the age of accountability, before we parents chasten them as sinners for wrongful actions, we should ask ourselves whether we have taught them the wrongfulness of that conduct. Have we taught them the commandments of God on that matter? This is a profound challenge and lesson for parents. Perhaps this is the underlying principle for the Lord’s solemn declaration that

inasmuch as parents have children in Zion, or in any of her stakes which are organized, that teach them not to understand the doctrine of repentance, faith in Christ the Son of the living God, and of baptism and the gift of the Holy Ghost by the laying on of the hands, when eight years old, the sin be upon the heads of the parents. [D&C 68:25]

The application of the commandments is sometimes difficult for children to understand. As parents we know that we must be constantly teaching our children how to apply the commandments to the varying circumstances of our lives. For example, without explicit teaching they may not understand that stealing services from a long-distance company is just as much a violation of the eighth commandment as stealing inventory from a retail merchant. In some of these teaching efforts, on matters that are genuinely in doubt, parents may need to treat an uninformed or untaught act as the equivalent of a mistake rather than as a sin. We should correct the youthful offenders and promptly teach them correct principles to guide their future actions. Any repetition would then be a transgression.

This redemptive procedure also applies in the definition of the adult transgression of apostasy for teaching false doctrine. Knowing that there may be genuine questions about what is false doctrine, the servants of the Lord have specified a procedure for protecting a member who strays over the line innocently. This kind of apostasy is defined as “persist[ing] in teaching as Church doctrine information that is not Church doctrine after being corrected by their bishops or higher authority” (General Handbook of Instructions 10–3). In other words, the teaching of false doctrine may be classified as a mistake the first time it happens, but it becomes a sin and a subject for Church discipline after those in authority clarify the application of the law to what the member is teaching.

Even though they have taught their children all of the commandments and principles they need for righteous and provident living, parents are still susceptible to the serious error of failing to distinguish between mistakes and sins. If well-meaning parents call teenagers to repentance for teenagers’ numerous mistakes, they may dilute the effect of chastisement and reduce the impact of repentance for the category of teenage sins that really require it. This point is well illustrated in an experience shared in an interview on Richard and Linda Eyre’s television series Families Are Forever.

The subject was the importance of being friends with our teenage children and creating an atmosphere in which they are free to communicate with us. In illustrating that important point, LDS filmmaker Kieth Merrill gave an equally valuable illustration of the importance of distinguishing between errors and transgressions in the correction of teenagers. His sixteen-year-old daughter had just begun to date. After discussion with her, he gave her strict instructions to be in by midnight. She was twenty minutes late. “I was very tired,” Brother Merrill said.

I had been suffering for twenty minutes because she was late. When she came in, I immediately read her the riot act. I forgot my policies. I forgot all my positive thinking. I forgot all the great things that I knew I should do. I just simply said, “You promised to be home at 12:00. You were not home at 12:00. I worry about you. We made a call. You weren’t where you said you would be. You said you would call.” And I went right down the list—bing, bing, bing, bing, negative, negative, negative, negative.

“Stop!” she said. . . . “We haven’t been drinking, we haven’t been smoking, we haven’t been immoral or unchaste. We didn’t go to any R-rated movie. We haven’t been to a party where there were drugs. We weren’t out shooting speed or doing anything else. We haven’t been making out, we haven’t been doing anything bad, Dad. I’m 15 minutes late for curfew, so let’s keep this in perspective.” And I totally fell on the floor and started to laugh. She totally shot me down because she felt that she could talk to me as a friend. [“Building Your Child’s Self-Esteem,” Families Are Forever, television series on VISN cable network, 1989]

That is a marvelous illustration of the importance of the scriptural direction that we only chasten and call to repentance for those actions that are sins. (Of course, at some extreme point or with repetition, the violation of a well-established curfew of dating times could be a sin, though even then it probably would not be as serious as the sins it was seeking to prevent.)

I hope we can remember these principles in the direction and disciplining of our children. I gave an earlier version of this talk to a small audience of priesthood and Relief Society members. Afterward, a brother whispered to me, “I sure wish I had heard about this distinction between errors and transgressions before I spent a week camping with the Boy Scouts in our ward.”

III

In the time that remains I will mention a few thoughts about some problems that lie along the uncertain border between sins and mistakes.

Sometimes it is not easy to tell the difference between a mistake and a sin. The boundary can be uncertain. Take the matter of the beautiful flowering crab tree in our front yard. One spring when the limbs of this tree were getting too long, I pruned them, quite severely. June, my wife, evaluated my pruning and told me she thought it was a sin. I thought the extent of my pruning was a mistake at worst. I was willing to be corrected, but I did not feel I was needful of chastening and repentance.

My experience with overpruning our flowering tree leads to the observation that there is a large category of undesirable conduct that is surely an error or mistake, and, at an extreme level, can cross over the border into transgression. When we willfully pass up an opportunity to progress toward eternal life, this is surely a mistake that should be corrected. In one way of looking at things, it is also a sin. This would apply to such things as failing to get schooling to prepare us for life, wasting our time, or failing to maintain the good grooming or to acquire the social or communication skills that would help us obtain employment or favorable consideration for marriage.

Mistakes can also lead to sins. The Prophet Joseph Smith observed that “there are so many fools in the world for the devil to operate upon, it gives him the advantage oftentimes” (Teachings, p. 331).

The violation of special limits like curfews or missionary rules can make one vulnerable to sin. Or a mistake committed by one person can lead another person into sin in attempting to correct it. The pruning of the flowering crab tree, and countless other mistakes that are the subject of communications between husbands and wives and among parents and children, can be mishandled to the point of producing the wrathful, angry behavior the scriptures call contention. Contention is always a transgression. This was the subject of the apostle Paul’s warning to the parents in Ephesus: “Provoke not your children to wrath: but bring them up in the nurture and admonition of the Lord” (Ephesians 6:4). The apostle James reminds us that “the wrath of man worketh not the righteousness of God” (James 1:20). We must be careful how we point out and correct mistakes in others, lest efforts to correct a small-sized mistake become an overreaction that produces an even larger transgression in us or in those we are attempting to help.

We should not conclude that a sin is always more serious than a mistake. Almost all sins, large and small, can be repented of, but some serious mistakes (like stepping in front of a speeding automobile) can be irreversible. This shows that a big mistake may have more serious permanent effects than a small transgression. To cite an example more benign than a pedestrian fatality, it is a sin to be insulting or unkind to anyone, but to be insulting or unkind to your boss is a big mistake. In this case, repentance for unkindness may be easier than finding a new job for insubordination.

The Prophet Joseph Smith identified another kind of error whose consequences may be more serious than those of some sins. He said that ignorance of the nature of evil spirits had caused many, including some members of the restored Church, to err in following false prophets and prophetesses. In an editorial in the Times and Seasons, the Prophet observed that “nothing is a greater injury to the children of men than to be under the influence of a false spirit when they think they have the Spirit of God” (HC 4:573). By this account, persons innocently misled by false spirits are guilty of error and can be readily welcomed back into the fold when their error has been made known and acknowledged. That very redemptive teaching rests on the scriptural distinction between errors and transgressions.

Another thing about the relationship of sins and mistakes is that they often go together. This serious truth is illustrated by some humorous examples in a pamphlet BYU’s J. Reuben Clark Law School published a few years ago as a tribute to Professor Woody Deem. The companion relationship between sins and mistakes is neatly captured in the title: Criminals Are Stupid. Here are some examples (see pp. 7, 14, 25 in Criminals Are Stupid: A Tribute to Woody Deem, 1990):

A bank robber stuffed $850 in his bag, ran outside, and found he had left his car keys at the teller’s window. When he returned to get his keys, he was met by a welcoming committee. Some bank robbers make their demand for cash by writing a note and handing it to the bank teller. Some of these robbers have assured their speedy apprehension by writing their robbery demand on the back of their personalized check or their phone bill. Another robber used the back of a letter that notified him of the time of his next appointment with his parole officer.

For sheer stupidity it is hard to match the mistake of the robber who put his demand note through the automated teller machine at the bank. When nothing happened, he shouted, “This is a stickup; give me the money quick.” When this was ignored, he whipped out his revolver, pumped two shots into the belly of the machine, and drove off. A policeman who heard the shots arrested him for attempted robbery and drunk driving.

Bank robbing sinners seem prone to mistakes, but no more so than the parolee who entered a florist shop and ordered flowers sent to his girlfriend. After this order was put in writing, he pulled a gun and held up the shop. The shop had the address of the girlfriend, so she got the flowers and the police got their man.

Finally, I cite the case of the burglar who ran away from a burgled house, forgetting that he had parked his car in the victim’s driveway. The next morning he missed his car and reported it stolen. When the police located the car, they were immediately aware that they had also identified a burglar.

Sometimes the same act can be an error or a sin according to what is in the mind of the actor. Something like an automobile collision that does great harm to another can be an error if it was unintended or a transgression if it was intended. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., highlighted the distinction between an unintended act and an intended one in his famous observation that “even a dog distinguishes between being stumbled over and being kicked” (O. W. Holmes,The Common Law, p. 3 [1881]).

The central message of this talk is that we should always seek to distinguish between sins and mistakes, in our own behavior and in the conduct of others. When we do so, the scriptures direct us to the proper corrective.

Sins result from willful disobedience of laws we have received by explicit teaching or by the Spirit of Christ that teaches every man the general principles of right and wrong. For sins, the remedy is to chasten and encourage repentance.

Mistakes result from ignorance of the laws of God or of the workings of the universe or of people he has created. For mistakes, the remedy is to correct the mistake, not to condemn the actor.

We must make every effort to avoid sin and to repent when we fall short. Through the atonement of Jesus Christ we can be forgiven of our sins through repentance and baptism and by earnestly striving to keep the commandments of God. Being cleansed from sin and receiving forgiveness and reconciliation with God through the atonement of Christ is the means by which we can achieve our divine destiny as children of God.

We should seek to avoid mistakes, since some mistakes have very painful consequences. But we do not seek to avoid mistakes at all costs. Mistakes are inevitable in the process of growth in mortality. To avoid all possibility of error is to avoid all possibility of growth. In the parable of the talents, the Savior told of a servant who was so anxious to minimize the risk of loss through a mistaken investment that he hid up his talent and did nothing with it. That servant was condemned by his Master (see Matthew 25:24–30).

If we are willing to be corrected for our mistakes—and that is a big if, since many who are mistake-prone are also correction-resistant—innocent mistakes can be a source of growth and progress.

We may suffer adversities and afflictions from our own mistakes or from the mistakes of others, but in this we have a comforting promise. The Lord, who suffered for the pains and afflictions of his people (see Alma 7:11; D&C 18:11, 133:53), has assured us through his prophet that he will consecrate our afflictions for our gain (see 2 Nephi 2:2, D&C 98:3). We can learn by experience, even from our innocent and inevitable mistakes, and our Savior will help us carry the burden of the afflictions that are inevitable in mortality. What he asks of us is to keep his commandments, to repent when we fall short, and to help and love one another as he has loved us (see John 13:34).

I testify that he is our Savior and that this is what he would have us do, in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

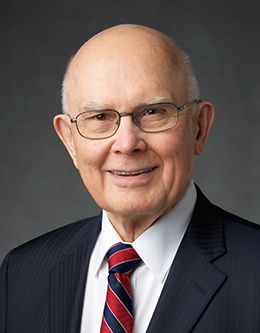

Dallin H. Oaks was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 16 August 1994.