The following season there arose a great persecution; the Saints were able to escape in the best manner they could. Joseph was carried away in a box nailed on an ox sled to save his life. Old father Joseph was taken out of a window in the night and sent away on horseback.

These are the words of Zera Pulsipher, a third-great-grandfather of mine and probably a number of you—he had a large posterity. He continues:

After most of the saints were gone to Missouri I remained in Kirtland with about four of the First Presidents of Seventies. We continued to hold our meetings in the Temple. Accordingly while we were at a meeting one Sunday, we took a notion to put our property together and remove in that way and when we had made that calculation we felt a great flow of the spirit of God, not withstanding the great inconvenience we labored under for want of means. We lacked means to move ourselves and many poor that were yet remaining had neither clothing nor teams to go with. But when they heard that we were going together and would help one another they wanted to join us and get out of that Hell of persecution. Therefore, we could not neglect them, for all there was against them was that they were poor and could not help themselves. We continued to receive them till we got between five and six hundred on our hands. We counciled together from time to time on the subject and came to the conclusion that we could not effect the purpose short of the marvelous power of God by the power of the Priesthood. Therefore, we concluded to best go into the Temple in the attic story and pray that our Father would open the way and give us means to gather with the saints in Missouri which was near a thousand miles away. Accordingly, one day while we were on our knees in prayer I saw a messenger apparently like an old man with white hair down to his shoulders. He was a very large man near seven feet high, dressed in a white robe down to his ankles. He looked on me then turned his eyes on the others and then to me again and spoke and said, “Be one and you shall have enough.” This gave us great joy; we immediately advised the brothers to scatter and work for anything that they could get that would be useful in moving to a new country. . . . A methodist meeting house stood a few rods from the Temple which took fire one night. . . . Most of the people being very hostile, the mob laid the charge of burning the house to the Council of Seventies . . . but we knew we were innocent and trusted in God. We continued our course steadily along and paid no attention to them. There was a universal determination that we should never leave that place in a company and they knew as well as we that the poor could not go out alone; therefore, they had a deep plot laid for our destruction. . . . But the Lord dictated to the great leader of that mob who had once been a Mormon and well calculated to carry out his devilish designs. . . . He had a vision and saw those that fired the house and seemed to be greatly astonished for a while and then met with the mob and informed them that it was not the Council that burned the house and he knew who it was but dared not tell on account of the law because he could prove only by vision, which they would not believe . . . But he swore by all the Gods that lived that he would have revenge on them if they lost a hair of our heads. He had a large store of goods and could swear and get drunk. He had some influence with them so that we were preserved by the hand of God. We obtained money and clothing for the company and the 4th day of July this man that had led the mob invited me to take all our teams and company and camp in a clover field which was about one feet high. I thanked him and embraced the offer. The next day we all went out all in order as we said we should in the beginning with about 65 teams and seventy cows.

I find this story meaningful. Who would have thought the Lord would help the Saints through a mob leader? Who would have thought the Lord would be so moved by their oneness of heart? It gets me thinking about my experiences here at BYU. In universities we often leave the poor behind—that is, we ignore the less educated; we even ignore those less acquainted with our own particular discipline. When we do bring each other along, on and off campus, I believe it pleases the Lord immensely and he opens the windows of heaven on our efforts in the most unexpected ways.

Today my topic is telling stories in the 21st century, and I would like to follow Zera’s lead and see how we can tell our stories so that others can come along with us. How can we tell stories that engage us all in understanding them? How can stories be meaningful not just to our families and us but to those with interests other than our own? Let’s look at a story from the Book of Mormon.

Nephi and his brothers have gone to Jerusalem to, somehow or other, get the brass plates, and their parents are waiting for their return. What will their parents do? What would you do in that situation?

Here is what Sariah does: She calls Lehi “a visionary man[,]saying: Behold thou hast led us forth from the land of our inheritance, and my sons are no more, and we perish in the wilderness” (1 Nephi 5:2).

What do you think of Sariah here? Nephi doesn’t tell us what to think. Instead, having told us her words, he lets us figure things out for ourselves. Notice how she calls her sons “my sons,” not “our sons.” She feels the loss of her sons as though it was just affecting her: “my sons are no more.” And notice how she speaks in the present tense: “my sons are no more, and we perish in the wilderness.” She feels everything bad coming in on her at once. Nephi writes, “And after this manner of language had my mother complained against my father” (v. 3). Why does Nephi mention the manner of her language? I think he wants us to notice the spirit of her criticism. Her spirit isn’t hidden deep inside her; it shows in her language.

Joseph Smith wrote, “It is in vain to try to hide a bad spirit from the eyes of them who are spiritual, for it will show itself in speaking and in writing, as well as in all our other conduct” (HC 1:317). Our spirit is our attitude, our orientation toward what is happening, continually reformed, moment by moment, in hardness or tenderness. Are we hard-heartedly holding onto ourselves by demeaning or ignoring what others are thinking or feeling or trying to do? Or are we tenderheartedly losing ourselves by bringing along something worthwhile of their spirit in ours? Are we being hard or tender? That is the question the Book of Mormon prompts us to ask.

Has Sariah hardened her heart against Lehi? Nephi doesn’t tell us. But he does tell us her words, many of which were used earlier by Laman and Lemuel when they murmuringly belittled their father and his decision to leave Jerusalem:

Laman and Lemuel . . . did murmur in many things against their father, because he was a visionary man, and had led them out of the land of Jerusalem, to leave the land of their inheritance, and their gold, and their silver, and their precious things, to perish in the wilderness.

Nephi concludes the passage with “And this they said he had done because of the foolish imaginations of his heart” (1 Nephi 2:11).

After Sariah has spoken in this spirit, how will Lehi respond to her? How would you respond if your wife was that upset and unsupportive? May we always remember his response. As much as Lehi can, he agrees with Sariah, repeating several of her phrases: “I know that I am a visionary man; for if I had not seen the things of God in a vision I should not have known the goodness of God, but had tarried at Jerusalem, and had perished with my brethren” (1 Nephi 5:4).

He then follows Sariah’s lead and speaks in the present tense about future events: “But behold, I have obtained a land of promise, in the which things I do rejoice.” And like her he calls his sons “my sons”: “Yea, and I know that the Lord will deliver my sons out of the hands of Laban, and bring them down again unto us in the wilderness” (v. 5).

Nephi then says, “And after this manner of language did my father, Lehi, comfort my mother, Sariah, concerning us” (v. 6). What is Nephi saying here about his father’s spirit? Comfort comes from the words com, meaning “with,” and forte, meaning “strong.” Lehi was with Sariah, strengthening her. He was bringing her along. He was tenderhearted. He was Christlike.

When Nephi and his brothers finally arrive, Sariah says:

Now I know of a surety that the Lord hath commanded my husband to flee into the wilderness; yea, and I also know of a surety that the Lord hath protected my sons, and delivered them out of the hands of Laban, and given them power whereby they could accomplish the thing which the Lord had commanded them. [v. 8]

Nephi adds, “And after this manner of language did she speak” (v. 8). Sariah’s spirit has changed. She is tenderly supporting Lehi.

Why does Nephi include this story? He didn’t need to. He could have simply glossed over the moment and said his mother was worried. Why show his mother behaving like this? Clearly, Nephi wasn’t there when this exchange took place between his parents, so he must have heard it from them or perhaps read it in his father’s account. Did he consider this a sacred story, something of great worth to his people and to us? He must have. I believe Nephi was writing in the great Biblical tradition of meaningful family stories.

Meaningful stories, like this one, aren’t about making ourselves look good or about telling the truth no matter how it makes us look. They aren’t about good guys being rewarded and bad guys punished. They needn’t be about miracles. Nor need they be about life-and-death situations. Meaningful stories aren’t about reconfirming what we all, deep down, already believe or want. Nor are they about opposing what we currently believe or desire.

Meaningful stories are first of all about characters, like Lehi and Sariah, coming to respond tenderly to each other and thus drawing us into responding tenderly to them ourselves. Meaningful stories are secondly about narrators tenderly dealing with their characters and their readers. When we tenderheartedly write about a hard-hearted character, we grieve; we mourn; we feel ashamed ourselves for the behavior of our character. When we tenderly tell a story, we don’t block our listeners’ participation in the story by nailing the story’s meaning down. Instead, we tell our story and submit it to our listeners and invite them to join with us in understanding what it means.

In effect, we invite our listeners to bear with us the responsibility for our story. That’s what Nephi was doing. That’s what sometimes happens in families; we tell our stories hoping that our loved ones can help us make sense of them. That’s what Zera was doing; he tells us the significant details—“The next day we all went out all in order as we said we should in the beginning with about 65 teams and seventy cows”—and he invites us to understand for ourselves what that wonderful exodus meant. Tenderhearted narrators and characters, inviting our tender response—that’s how meaningful stories work.

If our hearts are right, I believe we all can tell meaningful stories. And now, in the 21st century, with increasingly inexpensive yet high-quality digital cameras and editing systems for the common man, we can tell our meaningful stories in more ways than ever. Here are six ways.

First, we can photograph meaningful moments. My daughter Alisia lives in New York City and photographs people as she interacts with them. She never asks them to pretend that she and her camera aren’t there. Instead, she helps them relax and be at their best by engagingly talking with them. Along the way, she snaps a digital camera, shot after shot, hoping to catch their tender responses. She says she knows when a photo is going to be a good one. When she photographed Dennis Rasmussen, our department chair, she got into a conversation with him about Schopenhauer. At the time he wondered if they shouldn’t just concentrate on getting his picture taken. Later he understood how essential the conversation was.

Second, we can videotape meaningful moments. Cristy Welsh, a young mother who lives in my stake, brought two of her nephews together in a beautifully lit space, gave them something to do that she knew would be meaningful to them, and then videotaped them.

Third, we can recount meaningful moments. Here is a brief story written by my father about a moment in his childhood. When he retired, instead of sitting on a rocking chair and watching TV, he learned to type, took college writing classes, and read his stories over the radio. He is now working on a series of novels. Notice how he tenderly picks up the voice of himself as a child in this story, and how the child, in his own tender way, comes to feel the concerns of his parents.

Mama told me not to go upstairs in that bedroom—the one across from mine. She told me that, but I was only three, and she didn’t tell me why. I wanted to see. I knew baby Carter was in that room, so why couldn’t I go see?

Dee and Beth were on the living room floor [looking] at toys in the Christmas catalog. They kept the book all for them because they were older and bigger. They made it so I couldn’t see, and I didn’t like them. I went to the end of the room to get away, and I sat where the stairs turn to go up, and I watched them. Cleo couldn’t see the pictures good either. She was bigger than me, but she cried more, and she went for Mama to hold her. Mama always had something to sew, but this time she was on a rocker chair, by the barrel stove, just to be warm and look at the wall across the room. Cleo wanted Mama to hold her and squeak the rocking chair, so that she could stop crying and suck her thumb. Papa got a chunk of coal and put it in the barrel stove to keep the fire going.

When no one looked, I sneaked up to the room. It was cold in the room. There was nothing there but a dresser at the side of the door, with a wood box that Papa made sitting on top of it. I pulled the drawers out to make steps to go up like a ladder, and I climbed my way up. I reached up and held on the edge of the box so I could stand on a drawer and be tall enough to reach in.

I put my hand way down in. And my fingers touched something like skin, but it was cold and I jerked back. I knew it was baby Carter. I was sure it was. There was no other place in the room for him to be. But he was cold. Why was he so cold? And why wasn’t he crying?

I climbed down fast. I almost fell over the drawers. I ran out the door and down the stairs, but I hung onto the rail so I wouldn’t fall. Then I went slow so they wouldn’t know I was gone. I sat on a step to look through the spindles at Papa and Mama, so I could think.

Why isn’t Carter crying? Carter didn’t cry all day. Why isn’t Papa playing with Carter? Papa always plays with Carter in the evening. Why doesn’t Mama get Carter and nurse him like before? Why doesn’t Mama get Carter and bring him down here where it’s warm, and hold him and kiss him?

Do they know he’s cold?

Fourth, we can film our stories if we write them with scenes. An example is “Hamburger Soup,” on the BYU Web site lifesong.byu.edu. This piece was filmed with members of my stake. Youth in my stake are writing anecdotes like this for talks and filming them for stake cultural arts night. Another example on the site is called “Kelli’s Rose.” A freshman wrote the story, and another freshman videotaped the last scene of it.

Fifth, we can turn our accounts of meaningful moments into short novels. A number of such novels are currently in draft form at BYU, most written by students, some by alumni. A Boston-based company wants to publish three of these BYU novels every six months. Can we deliver? Of course we can. Will it be hard? It will take the best writers from across the campus and beyond. In Zera’s words, we won’t be able to “[a]ffect the purpose short of the marvelous power of God.”

Sixth, we can tell these longer stories in movie theaters. I have been reading the teachings of President Hinckley, and he writes:

Two of our Brethren were recently in Washington and called on three or four people of national prominence back there. Among those they met was the man who speaks for the motion-picture industry and now for the television industry on morality in the media. He said, in essence, to our Brethren, “We do what we can, but it is a well nigh impossible task to change the moral perspective of the media, writers, and programmers. There is only one force in America with enough clout to turn this thing around, and that is the Mormon Church.” [Gordon B. Hinckley, Teachings of Gordon B. Hinckley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1997), 333]

President Hinckley concludes, “What a tremendous compliment that is.”

Last semester, 90 accounting students, under the direction of professors Monte Swain and Shannon Leikem, wrote business plans for filming some of BYU’s short novels. Film production and distribution companies have stepped forward and expressed interest in cooperating with BYU in producing and distributing these films for theatrical release. To foster meaningful storytelling, BYU is also launching a television series of stories written and filmed by viewers like you.

We all have meaningful stories to tell. I know we do. If we tell them and let this marvelous generation of computer- and video-literate youth film them, I know we will draw others into tenderly telling their meaningful stories, too. Like Zera, we’ll be journeying toward Zion and bringing those who want to join us along. In the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

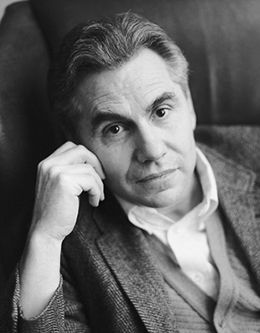

Dennis Packard was a professor of philosophy at Brigham Young University when this devotional address was given on 11 May 2004.