Catholics and Latter-day Saints: Partners in the Defense of Religious Freedom

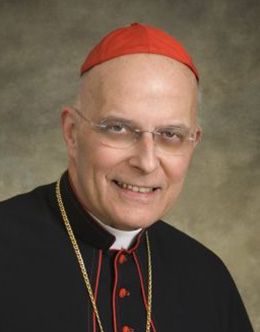

Archbishop of Chicago

February 23, 2010

Archbishop of Chicago

February 23, 2010

Thank you for your warm welcome, and thank you, President Samuelson, for your very kind introduction. As you point out, I am the Catholic Archbishop of Chicago and also the President of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. This dual role allows me to bring greetings from both the Catholic community of Chicago and from the Catholic bishops of this country to all of you—students, faculty, staff, and administration of this distinguished university, now marking its 135th year of service in higher education, and also to our guests from the surrounding community, many of whom I’m told are watching on satellite TV.

As a cardinal of the Holy Roman Church, I have a special bond with the Bishop of Rome, Pope Benedict XVI, whose specific service is one of preserving unity among Catholic believers everywhere and also of fostering peace and respect for human life and dignity among all people of goodwill. As a cardinal priest, that is, as a member of the clergy of Rome itself, quite apart from my being Archbishop of Chicago, I have the privilege and obligation to vote in a papal election. The cardinals assemble at the death of one pope in order to elect his successor because they are the clergy of Rome; but the choice of the Bishop of Rome, the one who sits in the chair of St. Peter, is, for us Catholics, we pray and hope and believe, in the hands of God, our Heavenly Father. Most important of all, I am a bishop of the Catholic Church and, therefore, a pastor to the people whom Christ Jesus has given me to love and to care for, first of all in two counties of Illinois, Cook and Lake Counties, which count 2.3 million baptized Catholics in the Archdiocese of Chicago, but also with a shared concern for all the Churches. Catholic bishops collectively oversee the Catholic Church with and under the Successor of Saint Peter, the head of the Apostolic College, the Bishop of Rome.

So I come before you today as a religious leader who shares with you a love for our own country but also, like many, a growing concern about its moral health as a good society. In recent years Catholics and members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have stood more frequently side by side in the public square to defend human life and dignity. In addition to working together to alleviate poverty here and abroad, we have been together in combating the degradations associated with the pornography industry; in promoting respect for the right to life of those still waiting in their mother’s womb to be born; and in defending marriage as the union of one man and one woman for the sake of family against various efforts to redefine in civil law that foundational element of God’s natural plan for creation. I am personally grateful that, after 180 years of living mostly apart from one another, Catholics and Latter-day Saints have begun to see one another as trustworthy partners in the defense of shared moral principles and in the promotion of the common good of our beloved country.

Of course, partnerships in causes of great moral import build on friendships and gestures of respect for one another’s identity, and these too have multiplied in recent years. The late and universally esteemed Latter-day Saint President, Gordon B. Hinckley, opened his door on many occasions to the past and present bishops of the Catholic Diocese of Salt Lake City, which encompasses all of Utah: Bishop George Niederauer, now Archbishop of San Francisco, and Bishop John C. Wester, who is with us today. Bishop Wester spearheads with great dedication the Catholic bishops’ national immigration reform efforts.

One of the high points of the centennial celebrations of the Catholic Cathedral of the Madeleine in Salt Lake City was the presence of LDS President Thomas S. Monson at a multi-faith service on August 10, 2009, honoring the cathedral’s civic engagements. At the service President Monson spoke eloquently about the enduring friendships that Catholics and Latter-day Saints have forged by together serving the needs of the poor and the most troubled of society. Through such shared dedication, he noted, we will “eliminate the weakness of one standing alone and substitute, instead, the strength of many working together” (Gerry Avant, “Joining Celebration at Catholic Cathedral,” Church News, 15 August 2009, 3). The service was marked by the presence of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.

I sometimes suspect, and maybe some of you do too, that Brigham Young and the first Catholic bishop of Salt Lake City, Lawrence Scanlan, would have been rather astonished at seeing the LDS First Presidency and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir helping local Catholics celebrate the anniversary of their cathedral. But good for them and good for us! I thank God for the harmony that has grown between us and for the possibilities of deepening our friendships through common witness and dialogue.

Let me mention one personal experience that stays with me, an experience with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, which I first heard when I was 13 years old. I visited Salt Lake City then with my mother, who was a good musician and who wanted to hear that great organ and the choir. The memory of that sound has stayed with me; it was overwhelming.

I had the great opportunity, through the kindness of the choir itself, to lead it once, on June 27, 2007. They were at the Ravinia music center in Highland Park, Illinois, outside of Chicago. A few days prior to the concert, I received a call from the choir’s music director, Dr. Craig Jessop, who asked whether I would consider assuming the conductor’s podium at the end of the performance and lead the choir in an encore number. Never had I been asked to do something like that! I seized the occasion, and, after a brief lesson from Craig at the dress rehearsal, I got up and faced the choir with a tremendous feeling of awe and power and great satisfaction. There was silence as this marvelous choir was looking at and waiting for me. If that doesn’t give you something of an ego trip, I don’t know what would! I paused for a moment, and then I gave the downbeat, according to Craig’s instruction. All of a sudden, that vacuum of expectant silence was filled with this magnificent, overpowering sound, all in unison, all in harmony. I thought to myself, “I’m doing better with the Mormons than I am with the Catholics!” I have a lot harder time getting them to sing together! What the choir sang was

This land is your land, this land is my land

From Wrigley’s diamond to the great Sears Tower,

From the Hancock Building to Lake Michigan’s waters,

This land was made for you and me.

What I’d like to do now in the short time available to us is to make three points. First of all, to share with you the Catholic understanding of religious freedom, which I think we share together: Religious freedom cannot be reduced to freedom of worship or even freedom of private conscience. Religious freedom means that religious groups as well as religious individuals have a right to exercise their influence in the public square. Any attempt to reduce that fuller sense of religious freedom, which has been part of our history in this country for more than two centuries, to a private reality of worship and individual conscience as long as you don’t make anybody else unhappy is not in our tradition. It was the tradition of the Soviet Union, where Lenin permitted freedom of worship (it was in the constitution of the Soviet Union) but not freedom of religion. Lenin was drawing on several antecedents, one of whom was Napoleon Bonaparte, who made civil peace after the terror of the French Revolution by limiting the Church to the sacristy but not permitting it to have a public role. This is not the American tradition, even though it is now argued by some Americans that it should be.

The second point I want to examine is the mounting threats to religious freedom in America. Thirdly and lastly, I want to show why it is that Catholics and Mormons do stand together and shall continue to do so with other defenders of conscience and the public exercise of religion.

We start with what the Mormon Tabernacle Choir sang in Chicago: this land is our land, a land of many peoples of differing religious convictions and political views, who will continue to differ in those convictions but who can come together for the sake of social harmony and the common good that we must all share. We Americans are “dedicated to the proposition that all men [and women] are created equal” (Abraham Lincoln, the Gettysburg Address) and that all people, no matter their respective beliefs, have equal protection under law. This 234-year-old experiment in self-government has made this land, our land, a place where both our religious communities and many others, with the help of God, have been able to flourish.

In 1634 a few dozen Catholics, precursors to millions of others of all faiths who would seek protection in this nation of immigrants, sailed on the Ark and the Dove from England to the shores of Maryland, where they and their associates would establish the first English-speaking Catholic community in America at a time when Catholicism was still proscribed in the British Empire, where it was against the law to build a Catholic church. They gathered in their own homes until the time of the American Revolution. The first Catholic bishop of this country, John Carroll, the Bishop of Baltimore, Maryland, was profoundly grateful for the First Amendment of our Constitution, which permitted the Church to come out, not only out of the sacristies but out of the basements of their own homes, and to take part in public life. That small Catholic community would grow to 67 million Catholics here today.

As you know, around 70,000 Mormon pioneers made the dangerous journey with Brigham Young to Utah in the period of 1847–68, and today the Latter-day Saints number 6 million in the United States and more than that—7 million—abroad.

The lesson of American history is that churches and other religious bodies prosper in a nation and in a social order that respects religious freedom and recognizes that civil government should never stand between the consciences and the religious practice of its citizens and Almighty God. The Founding Fathers understood when they amended the Constitution that the separation of church and state springs from a concept of limited government and favors a public role for churches and other religious bodies in promoting the civic virtues that are vitally necessary in a well-functioning democracy. But Catholic memories go back further than this. It was Pope Gelasius I who told Emperor Anastasius I, “Two there are,” when the emperor was trying to run the Catholic Church as well as the empire. That institutional separation remains integral to the Church’s self-identity, although how it is worked out varies, depending upon the particular government, the particular area, and the particular culture.

The Catholic Church did not always understand and appreciate that religious freedom is compatible with democratic government, with liberal democracy. That is because throughout much of the 19th century, Catholic leaders in Europe could not distinguish between the antireligious furor unleashed by the Jacobin terror of the French Revolution in the name of democracy and the United States’ defense of liberty based on the natural rights of man in our own democratic experiment. The Catholic Church came to terms fully with what is positive in the movement to defend democracy and human rights in that context only in the late 19th century, when Pope Leo XIII began the tradition of issuing modern social encyclicals.

At that time, the Pope wrote on the economic rights and duties of capital and labor in an encyclical called by its first two Latin words, Rerum Novarum (1891). He tried to defend labor against the power of capital by telling laborers to organize into unions so that the dialogue would be a little more equal; but his basic concern was the condition of the family in an economy that was moving from an agricultural base to an industrial base. In an agricultural economy, the family is also an economic unit; it was work that helped keep mother, father, and children together. In an industrially based economy, the Pope saw the father in the factory working apart from his family, the mother who was perhaps in the home of someone who owned a factory, working as a maid, and the children who were very often on the streets. Because of that social disorder, a number of religious orders began in the late 19th century. I think particularly of the Salesian Fathers, who took boys from the streets, literally, because they no longer had a home, and educated them and gave them a second kind of home. In an attempt to teach that work must continue to protect the family and not destroy it, Pope Leo XIII wrote about a family wage. A worker would be paid not only for work to be performed but also for responsibilities to be met.

Behind the family wage, there is the basic conviction that it is not individuals and their rights that are the basis of society, although they might be the basis of a political order, but it is the family that is the basic unit of society: mothers and fathers who have duties and obligations to their children and children who learn how to be human in the school of love, which is the family. The family tells us that we’re not the center of the world individually but are rather always someone’s son, someone’s daughter, someone’s brother or sister or cousin or uncle. The family relationships are prior to individual self-consciousness. That is the basis of Catholic social teaching; it is ineluctably a communitarian ethos.

In this country we have to pay “equal pay for equal work,” which is defensible when you take equality as a sign of justice. Nonetheless, we also have to accommodate family obligations, and that is done by paying benefits. Benefits are based on relationships, and it is relationships that count, finally, in Catholic social teaching. If you want to understand where the bishops are coming from, where Catholic social theory is coming from on any particular issue, ask the question, “How will this policy or proposal affect the family?”

At the Second Vatican Council, which was held from 1962 to 1965, when I was a seminarian, the Catholic Church praised constitutional limits on the powers of government, and it also taught that constitutional guarantees of religious freedom for all people in every place are necessary to have a just society.

In the Declaration on Religious Freedom (Dignitatis Humanae) in 1965, from that same Council, the affirmation was made that churches and religious organizations must be free to govern themselves and to pursue their goals of education outside of the sacristy, through programs for the formation of believers (in youth groups and catechetical conferences and other instances), through charitable pursuits on the streets, outside of the sacristy, and through working for the advance of justice in society, outside of the sacristy.

The difference in the teaching, the development of doctrine that took place at the Second Vatican Council, was that the Church focused the locus of those rights not in institutions, whether church or state, but rather in persons and talked about the anthropology of the human person as made in the image and likeness of God and, therefore, made to be free.

Civil laws and obligations should protect that personal freedom; the basis of it all is religious freedom, because it is our relationship to God that determines our relationship to everyone else. We are related to God, who is Creator and Savior and Sanctifier, and then related to everyone God loves; so we must see others, in some sense, as brothers and sisters, as members of the one human family, no matter what other differences there might be.

Vatican II was the immediate background for the role assumed by one of the most remarkable figures of the 20th century, Karol Wojtyla of Poland, who became in 1978 the 264th pope. Up until his death from Parkinson’s disease in 2005, Pope John Paul II was one of the most successful evangelists in modern times, making 104 foreign trips and covering more than 750,000 miles so that he could preach the gospel of Jesus Christ in many tongues and to many cultures. His aim was always, first, to strengthen the spiritual lives of his own flock and to be, at the same time, a powerful advocate for human rights in every land where he set foot.

John Paul II’s visit to his homeland of Poland in 1979, shortly after his election, set in motion the emergence of the first independent trade union in communist Eastern Europe, Solidarność (Solidarity), which set off a chain reaction that would, within a decade, bring down the Iron Curtain. When asked years later about his role in the collapse of communism—acknowledged by principal actors like Mikhail Gorbachev to have been vitally instrumental, Pope John Paul II said self-effacingly, and also what he believed, “I didn’t cause this to happen. The tree was already rotten. I just gave it a good shake” (in Carl Bernstein and Marco Politi, His Holiness: John Paul II and the History of Our Time [New York: Penguin, 1997], 356). He saw, even before many in our own state department saw, that the Soviet Union could not last. Why? Because, with a philosophical and theological eye, he saw that a social order that opposed personal freedom to social justice was inherently unstable. To hold that in order to have social justice you have to sacrifice personal freedom is to create a social order at odds with human nature.

What we sometimes forget is that this same pope, speaking to our own culture, said you cannot play off personal freedom against objective truth. Therefore, the truth question must be public, even the religious truth question, and there are canons of intellectual pursuit that are in place to examine it. You cannot put objective moral and religious truths aside and imagine that you can build a social order that safeguards individual freedom by suppressing objective truth; yet that is our system, and we must ask with the Pope, “Is it sustainable?”

John Paul II poured his heart into the defense of religious freedom, but not primarily as a politician on the world stage. He denounced evils like racism, human trafficking, abortion, euthanasia, and the exploitation of workers and immigrants, but his approach was from the vantage point of a pastor to whom Christ had entrusted the mission to teach and care for the least of the Lord’s brothers and sisters (see Matthew 25:40). He was also a philosopher by training, someone who had assimilated the reflections of the great thinkers of the Western tradition and who recognized that the question of freedom lies at the heart of modern society’s deepest conflicts, because it always lies at the heart of who we are as creatures made in the image and likeness of a God who loves us freely. For the philosopher-pope, freedom is not the entitlement to do whatever one pleases, to pursue one’s individual dream. It is not the pretext for moral anarchy, but the capacity to fulfill one’s deepest aspirations by choosing the true and the good in the human community. This is what distinguishes human beings from other living creatures: we can know the truth about God and about ourselves as creatures with inviolable dignity precisely because we are made in God’s image and likeness (Genesis 1:26). Therefore, freedom of religion was for the Pope, and for the tradition out of which he spoke, the most fundamental human right and the precious achievement of any good society.

I think in all this, while with different words sometimes, Mormons and Catholics can come together with a great deal of agreement and work together to try to be sure that our society doesn’t have that cultural fault line that continuously pits personal and individual liberties against objective truth, or at least the search for it, including the search for religious truths, even if we don’t come to common agreement.

There are—and this is my second point—threats to religious freedom in America that are new to our history and to our tradition. We have seen this with particular clarity in areas that would seem, at first blush, to have little to do with religious freedom—in the question of health care and in the question of human sexuality.

Threats to conscience in health care have become prominent recently, particularly in the context of our discussion about health-care-reform legislation. Yet those threats were there already long before in Supreme Court decisions and sometimes in legislation in parts of our country, particularly around the protection of those waiting to be born.

Once Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973, some advocates for abortion would interpret that decision even more broadly than it was drawn, in a way that would threaten the consciences of Catholic and other health-care workers and institutions. Specifically, they argued Roe v. Wade did not merely declare a right to have the government not interfere with a woman’s privacy but also the right to have the government positively assist in a woman’s having an abortion, whether by government’s funding of the abortion and, therefore, using our money in such a way that we all become complicit in what we regard as a morally heinous act or by government’s inducing or compelling others to provide the abortion. If the civil law were to impose such pressures and duties to assist in provision of abortion and other immoral procedures, then freedom of conscience would be directly threatened.

In order to be sure this didn’t happen, members of Congress passed a number of amendments and laws to qualify the Roe v. Wadedecision. They passed a law called the Church Amendment, named after the legislator, which made clear that hospitals receiving federal funds are not thereby obliged to provide abortions. It also protects an employee who refuses to participate in that kind of procedure from any kind of employer discipline. In 1976 the Hyde Amendment was passed; it prohibits the use of federal Medicaid funds to pay for elective abortions, whether directly by reimbursement for the cost or indirectly by subsidizing health insurance coverage that includes abortion.

These laws have remained in place for over three decades, and even stronger protections have been added. The Weldon Amendment forbids states receiving federal health-care dollars from punishing individual or institutional health-care providers who, for reasons of conscience, will not provide abortions or abortion referrals. All these are still in place, but what is in question now is how they will survive the present health-care debate.

In that debate the Catholic bishops have tried to play a role as a moral voice, not as politicians. It’s hard to maintain that stance in the public sphere because the media talk about politics and personalities, and very seldom will they rise to the level of principle. In the realm of moral principle, the bishops have stressed two points: First, that everyone should be taken care of. We need to look at health-care reform. There are pregnant women who don’t have the prenatal care they should have; there are people with preexisting health conditions who cannot get insurance; there are too many gaps in our care and too many people aren’t being taken care of by the government or by hospitals or by private philanthropy. Everyone should be cared for, but it’s not the bishops’ job to say how.

The second moral point is that no one should be deliberately killed. Health care doesn’t include euthanasia and doesn’t include abortion; those are killings, not treatments. Those are the two moral principles that the Catholic bishops have insisted on, with the risk of being captured by one party on the need for universal care and by the other on removing killing from it.

The second area of conflict today posing a threat to religious freedom is human sexuality, especially in the development of gay rights and the call for same-sex “marriage.” Again, with the LDS Church, Catholics would insist that every single person is made in God’s image and likeness. Every single person, no matter his or her sexual orientation, must be respected as an individual; everyone must be loved because they are loved by God. Loving someone, however, doesn’t mean that one approves of everything they do.

With the advocates of same-sex “marriage” legislation, we can expect a one-two punch from hostile governments, whether locally or perhaps federally. We will see, first, attempts to compel traditional religious organizations to afford same-sex, civilly married couples the same special solicitude that they afford actually married couples, whether in the provision of employment benefits, adoption services, or any of a number of other areas where religious groups operate in the broader society and where rights hinge on whether or not one is civilly married. If this first wave is successfully resisted, there will be a second series of government punishments for that persistence. We will lose state or local government contracts, tax exemptions, anything else that could be characterized as a “subsidy” for our “discrimination.”

There is nothing conjectural about these risks. In Massachusetts, Catholic Charities had to move out of placing children for adoption after over 100 years of being involved in that charitable enterprise. Now, in the District of Columbia, Catholic Charities, the Archdiocese of Washington, and our own headquarters of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, as well as of the Military Ordinariate, have to come to terms with a law just passed recognizing same-sex “marriages,” without any religious exemption, and that done very deliberately.

These examples illustrate the threats to religious freedom in America. It’s not at all agreeable to get into a context that plays off individual liberties against the liberty of religious bodies themselves. At some point, I suppose, it will have to go to the courts, which finally decide what are the terms of our living together. What I most regret is not so much the opposition but the misunderstanding, deliberate or not. Those of us who have gay people in our family, as I have, know the anxieties and deep conflicts in their own lives, and we have to be there for them and love them and support them. But when, in public life, what is wanted politically is not given, as happened with Proposition 8 in California, and the response is thuggery, then the common good of our whole society stands in great jeopardy.

Dear friends, I believe, lastly, that Catholics and Mormons stand with one another and with other defenders of conscience and that we can and should stand as one in the defense of religious liberty. In the coming years, interreligious coalitions formed to defend the rights of conscience for individuals and for religious institutions should become a vital bulwark against the tide of forces at work in our government and society to reduce religion to a purely private reality.

At stake is whether or not the religious voice will maintain its right to be heard in the public square. Our collaborative efforts in this work may include common statements and court testimonies, demonstrating principles that are consonant with our religious beliefs, even as they are expressed in the language of law and human reason. Sometimes our common advocacy will make one of us the target of retribution by intolerant elements. But, despite that, if we stay together and go forward together, the good sense, the common sense, and the generosity of the majority of people, as well as the love that is truly present through God’s grace in the hearts of all people will, I believe, bear much fruit.

When government fails to protect the consciences of its citizens, it falls to religious bodies—especially those formed by the gospel of Jesus Christ—to become the defenders of human freedom. If this continues to be our shared calling, one to which we invite others, then we will defend religious liberty first of all for the good of law itself, knowing that good law protects everyone’s rights, no matter how feeble they might be. That’s the purpose of law: to defend those who otherwise could not defend themselves. We will be together in this struggle for the good of society itself, believing with Alexis de Tocqueville that churches and religious bodies play a crucial role, a mediating role, in fostering a nation’s civic life.

Finally, we will work together because it is for the good of the people whom we shepherd in our own communities: Mormons and Catholics who take pride in our citizenship as Americans and in our legacy of service to the nation, and who continue to claim full citizenship in this pluralistic country.

Our churches have different histories and systems of belief and practice, although we acknowledge a common reference point in the person and in the gospel of Jesus Christ. It strikes me that, however different our historic journeys and creeds might be, our communities share a common experience of being a religious minority that was persecuted in different ways in mid-19th-century America. We know that religious conviction combined with America’s founding vision of religious liberty and justice for all was what sustained our people in a hostile environment and eventually enabled them to emerge from their enclaves to make a very great and significant contribution to the political and cultural life of our nation. It is, therefore, true, especially of our two groups, the Latter-day Saints and the Catholic Church, that the defense of religious liberty affirms what is deepest in our self-identity.

Dear sisters and brothers, years ago Mother Teresa of Calcutta, the saint who spent her life caring for the sick and the extremely destitute, was bringing supplies to a Palestinian orphanage in the Gaza region of the Holy Land. At one point her vehicle came up to a checkpoint, and a young Israeli soldier asked the diminutive nun whether she or her assistants were carrying any weapons. Mother Teresa replied, “Yes, my prayer books.”

Perhaps in the struggle to defend religious liberty for our churches and for all Americans, our greatest weapon is neither the voting booth nor the legal brief but the prayers that we and our worshipping communities lift up to Almighty God week after week on behalf of our nation.

My prayer for all of us here today is that we become true blessings to one another in the shared work of advocacy for human rights and dignity so that together we may become a true blessing for the world. I thank you for your kind attention.

© Francis E. George.

His Eminence Francis Cardinal George, OMI, was President of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and Archbishop of Chicago when he gave this forum address at Brigham Young University on 23 February 2010.