Thank you very much, Bob. I appreciate this great privilege each time that it is mine, my brothers and sisters. I am grateful to the choral group today for that last number, the lyrics of which I hope will linger with you somewhat, because I will turn to them as I close my speech.

I have chosen to speak today about a very pedestrian principle: patience, I hope that I do not empty the Marriott Center by that selection. Perhaps the topic was selfishly selected because of my clear and continuing need to develop further this very important attribute. But my interest in patience is not solely personal; for the necessity of having this intriguing attribute is cited several times in the scriptures, including once by King Benjamin who, when clustering the attributes of sainthood, named patience as a charter member of that cluster (Mosiah 3:19; see also Alma 7:23).

Patience is not indifference. Actually, it means caring very much but being willing, nevertheless, to submit to the Lord and to what the scriptures call the “process of time.”

Patience is tied very closely to faith in our Heavenly Father. Actually, when we are unduly impatient we are suggesting that we know what is best—better than does God. Or, at least, we are asserting that our timetable is better than His. Either way we are questioning the reality of God’s omniscience as if, as some seem to believe, God were on some sort of postdoctoral fellowship and were not quite in charge of everything.

Saint Teresa of Avila said that unless we come to know the reality of God, including his omniscience, our mortal existence “will be no more than a night in a second-class hotel” (quoted by Malcolm Muggeridge in “The Great Liberal Death Wish,” Imprimis [Hillsdale College, Michigan], May 1979.) Our second estate can be a first-class experience only if you and I develop a patient faith in God and in his unfolding purposes.

We read in Mosiah about how the Lord simultaneously tries the patience of His people even as He tries their faith (Mosiah 23:21). One is not only to endure, but to endure well and gracefully those things which the Lord “seeth fit to inflict upon [us]” (Mosiah 3:19), just as did a group of ancient American saints who were bearing unusual burdens but who submitted “cheerfully and with patience to all the will of the Lord” (Mosiah 24:15).

Paul, speaking to the Hebrews, brings us up short by writing that, even after faithful disciples had “done the will of God,” they “[had] need of patience” (Hebrews 10:36). How many times have good individuals done the right thing only to break or wear away under subsequent stress, canceling out much of the value of what they had already so painstakingly done? Sometimes that which we are doing is correct enough but simply needs to be persisted in patiently, not for a minute or a moment but sometimes for years. Paul speaks of the marathon of life and of how we must “run with patience the race that is set before us” (Hebrews 12:1). Paul did not select the hundred-meter dash for his analogy!

The Lord has twice said: “And seek the face of the Lord always, that in patience ye may possess your souls, and ye shall have eternal life” (D&C 101:38, emphasis added; see also Luke 21:19). Could it be, brothers and sisters, that only when our self-control becomes total do we come into the true possession of our souls?

Patience is not only a companion of faith but is also a friend to free agency. Inside our impatience there is sometimes an ugly reality: We are plainly irritated and inconvenienced by the need to make allowance for the free agency of others. In our impatience—which is not the same thing as divine discontent—we would override others, even though it is obvious that our individual differences and preferences are so irretrievably enmeshed with each other that the only resolution which preserves free agency is our patience and longsuffering with each other.

The passage of time is not, by itself, an automatic cure for bad choices; but often individuals like the prodigal son can “in process of time” come to their senses. The touching reunion of Jacob and Esau in the desert, so many years after their youthful rivalry, is a classic example of how generosity can replace animosity when truth is mixed with time. When we are unduly impatient, we are, in effect, trying to hasten an outcome when this kind of acceleration would be to abuse agency. Enoch—brilliant, submissive, and spiritual—knew what it meant to see a whole city-culture advance in “process of time.” He could tell us much about so many things, including patience. Patience makes possible a personal spiritual symmetry which arises only, brothers and sisters, from prolonged obedience within free agency.

There is also a dimension of patience which links it to a special reverence for life. Patience is a willingness, in a sense, to watch the unfolding purposes of God with a sense of wonder and awe, rather than pacing up and down within the cell of our circumstance. Put another way, too much anxious opening of the oven door and the cake falls instead of rising. So it is with us. If we are always selfishly taking our temperature to see if we are happy, we will not be.

When we are impatient, we are neither reverential nor reflective because we are too self-centered. Whereas faith and patience are companions, so are selfishness and impatience. It is so easy to be confrontive without being informative; so easy to be indignant without being intelligent; so easy to be impulsive without being insightful. It is so easy to command others when we are not in control of ourselves.

I remember as a child going eagerly to the corner store for what we then called an “all-day sucker.” It would not have lasted all day under the best usage, but it could last quite awhile. The trick was to resist the temptation to bite into it, to learn to savor rather than to crunch and chew. The same savoring was needed with a precious square of Hershey milk chocolate to make the treat last, especially in depression times.

In life, however, even patiently stretching out sweetness is sometimes not enough; in certain situations, enjoyment must actually be deferred. A patient willingness to defer dividends is a hallmark of individual maturity. It is, parenthetically, a hallmark of free nations that their citizens can discipline themselves today for a better tomorrow. Yet America is in trouble (as are other nations) precisely because a patient persistence in a wise course of public policy is so difficult to attain. Too many impatient politicians buy today‘s votes with tomorrow‘s inflation.

But back to the personal relevance of patience which, among many things, permits us to deal more effectively with the unevenness of life‘s experiences. I recorded the substance of this speech about three months ago while driving to a stake conference in Elko, Nevada, across that rather barren, but beautiful in its own way, stretch of desert. (Incidentally, as soon as most of this speech on patience was dictated my car threw two fan belts!) During that drive, it was brought forcibly to me that the seeming flat periods of life give us a blessed chance to reflect upon what is past as well as to be readied for some rather stirring climbs ahead. Instead of grumbling and murmuring, we should be consolidating and reflecting, which would not be possible if life were an uninterrupted sequence of fantastic scenery, confrontive events, and exhilarating conversation.

Patience helps us to use, rather than to protest, these seeming flat periods of life, becoming filled with quiet wonder over the past and with anticipation for that which may lie ahead, instead of demeaning the particular flatness through which we may be passing at the time. We should savor even the seemingly ordinary times, for life cannot be made up all of kettledrums and crashing cymbals. There must be some flutes and violins. Living cannot be all crescendo; there must be some dynamic contrast.

Clearly, without patience we will learn less in life. We will see less; we will feel less; we will hear less. Ironically, “rush” and “more” usually mean “less.” The pressure of “now,” time and time again, go against the grain of the gospel with its eternalism.

There is also in patience a greater opportunity for that discernment which sorts out the things that matter most from the things that matter least. The mealtime episode of the Savior in the home of Mary and Martha is an example. Anxious, impatient Martha focused on getting food on the table while Mary wisely chose “the good part”—companionship and conversation instead of calories—a good choice, the Savior said, which would not be taken from her.

In our approach to life, patience also helps us to realize that while we may be ready to move on, having had enough of a particular learning experience, our continued presence is often needed as a part of the learning environment of others. Patience is thus closely connected with two other central attributes of Christianity—love and humility. Paul said to the saints at Thessalonica, “Be patient toward all men”—clearly a part of keeping the second great commandment (1 Thessalonians 5:14).

The patient person assumes that what others have to say is worth listening to. A patient person is not so chronically eager to put forth his or her own ideas. In true humility, we do some waiting upon others. We value them for what they say and what they have to contribute. Patience and humility are special friends.

Since our competition in life, as Elder Boyd K. Packer has perceptively said, is solely with our old self, we ought to be free, you and I, as members of the Church, from the jealousies and anxieties of the world which go with interpersonal competition. Very importantly, it is patience, when combined with love, which permits us “in process of time” to detoxify our disappointments. Patience and love take the radioactivity out of our resentments. These are neither small nor occasional needs in most of our lives.

Further, the patient person can better understand how there are circumstances when, if our hearts are set too much upon the things of this world, they must be broken—but for our sakes, and not merely as a demonstration of divine power. But it takes real patience in such circumstances to wait for the later vindication of our trust in the Lord.

Therefore, if we use the process of time well, it can cradle us as we develop patient humility. Keats tenderly observed: “Time, that aged nurse, /Rock‘d me to patience” (John Bartlett, Familiar Quotations, 14th ed. [Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1968], p. 580). Clearly, patience so cradles us when we are in the midst of suffering. Paul, who suffered much, observed in his epistle to the Hebrews: “Now no chastening for the present seemeth to be joyous, but grievous: nevertheless afterward it yieldeth the peaceable fruit of righteousness unto them which are exercised thereby” (Hebrews 12:11).

Patience permits us to cling to our faith in the Lord when we are tossed about by suffering as if by surf. When the undertow grasps us, we will realize that even as we tumble we are somehow being carried forward; we are actually being helped even as we cry for help.

One of the functions of the tribulations of the righteous is that “tribulation worketh patience” (Romans 5:3). What a vital attribute patience is if tribulation is worth enduring to bring about its development! Patience in turn brings about the needed experience, as noted in the stunning insight the Lord gave to the Prophet Joseph Smith: “All these things shall give thee experience, and shall be for thy good” (D&C 122:7). Perhaps one can be forgiven if, in response to this sobering insight, his soul shivers just a bit. James also stressed the importance of patience when our faith is being tried, because those grueling experiences “[work] patience,” and said, in what was almost a sigh of the soul, “Let patience have her perfect work . . .” (James 1:3-4).

To Joseph Smith, the Lord described patience as having a special finishing and concluding quality, for “These things remain to overcome through patience, that such may receive a more exceeding and eternal weight of glory” (D&C 63:66). A patient disciple, for instance, will not be surprised nor undone when the Church is misrepresented. Peter, being toughminded as well as tender, made the test of our patience even more precise and demanding when he said, “For what glory is it, if, when ye be buffeted for your faults, ye shall take it patiently? but if, when ye do well, and suffer for it, ye take it patiently, this is acceptable with God” (1 Peter 2:20). The dues of discipleship are high indeed, and how much we can take so often determines how much we can then give. I believe it was George MacDonald who observed that, in the process of life, we are not always the already-tempered and helpful hammer which is shaping and pounding another. Sometimes we are merely the anvil.

Thus, as already indicated, patience is a vital mortal virtue in relation to our faith, our free agency, our attitude toward life, our humility, and our suffering. Moreover, patience will not be an obsolete attribute in the next world.

My brothers and sisters, the longer I examine the gospel of Jesus Christ, the more I understand that the Lord‘s commitment to free agency is very deep—indeed, much deeper than is our own. The more I live, the more I also sense how exquisite is His perfect love of us. It is, in fact, the very interplay of God’s everlasting commitment to free agency and His everlasting and perfect love for us which inevitably places a high premium upon the virtue of patience. There is simply no other way for true growth to occur.

God’s attributes of omniscience and omnipotence no doubt made the plan of salvation feasible. But it was His perfect love which made the plan inevitable. And it is His perfect patience which makes it sustainable. Do we not, again and again, get breathtaking glimpses of God’s perfect patience in the execution of the plan of salvation, concerning which He has said that his “course is one eternal round” (D&C 3:2)?

Thus it is that patience is to human nature what photosynthesis is to nature. Photosynthesis, the most important single chemical reaction we know, brings together water, light, chlorophyll, and carbon dioxide, processing annually the hundreds of trillions of tons of carbon dioxide and converting them to oxygen as part of the process of making food and fuel. The marvelous process of photosynthesis is crucial to life on this planet, and it is a very constant and patient process. So, too, is an individual‘s spiritual growth. Neither patience nor photosynthesis are conspicuous processes.

Patience is always involved in the spiritual chemistry of the soul, not only when we try to turn the trials and tribulations—the carbon dioxide, as it were—into joy and growth, but also when we use it to build upon the seemingly ordinary experiences to bring about happy and spiritual outcomes.

Patience is, therefore, clearly not fatalistic, shoulder-shrugging resignation. It is the acceptance of a divine rhythm to life; it is obedience prolonged. Patience stoutly resists pulling up the daisies to see how the roots are doing. Patience is never condescending or exclusive—it is never glad when others are left out. Patience never preens itself; it prefers keeping the window of the soul open.

I have struggled to find adequate words to express these concluding feelings and these thoughts about our need to be patient with ourselves and with our circumstances in this second estate.

Some of us have been momentarily wrenched by the sound of a train whistle spilling into the night air, and we have been inexplicably subdued by the mix of feelings that this evokes. Or perhaps we have been beckoned by a lighted cottage across a snow-covered meadow at dusk. Or we have heard the warm and drawing laughter of children at a nearby playground. Or we have been tugged at by the strains of congregational singing from a nearby church. Or we have encountered a particular fragrance which has awakened memories deep within us of things which once were. In such moments, we have felt a deep yearning, as if we were temporarily outside of something to which we actually belonged and of which we so much wanted again to be a part.

There are spiritual equivalents of these moments. Such seem to occur most often when time touches eternity. In these moments we feel a longing closeness—but we are still separate. The partition which produces this paradox is something we call the veil—a partition the presence of which requires our patience. We define the veil as the border between mortality and eternity; it is also a film of forgetting which covers the memories of earlier experiences. This forgetfulness will be lifted one day, and on that day we will see forever—rather than “through a glass, darkly” (1 Corinthians 13:12).

There are poignant and frequent reminders of the veil, adding to our sense of being close but still outside. In our deepest prayers, when the agency of man encounters the omniscience of God, we sometimes sense, if only momentarily, how very provincial our petitions are; we perceive that there are more good answers than we have good questions; and we realize that we have been taught more than we can tell, for the language used is not that which the tongue can transmit.

We experience this same close separateness when a baby is born, but also as we wait with those who are dying—for then we brush against the veil, as goodbyes and greetings are said almost within earshot of each other. In such moments, this resonance with realities on the other side of the veil is so obvious that it can be explained in only one way!

No wonder the Savior said that His doctrines would be recognized by His sheep, that we would know His voice, that we would follow Him (John 10:14). We do not, therefore, follow strangers. Deep within us, His doctrines do strike the promised chord of familiarity and underscore our true identity. Our sense of belonging grows in spite of our sense of separateness; for His teachings stir our souls, awakening feelings within us which have somehow survived underneath the encrusting experiences of mortality.

This inner serenity which the believer knows as he brushes against the veil is cousin to certitude. The peace it brings surpasses our understanding and certainly our capacity to explain. But it requires a patience which stands in stark contrast to the restlessness of the world in which, said Isaiah, the wicked are like the pounding and troubled sea which cannot rest (Isaiah 57:20).

But mercifully the veil is there. It is fixed by the wisdom of God for our good. It is no use being impatient with the Lord over that reality, for it is clearly a condition to which we agreed so long ago. Even when the veil is parted briefly, it will be on His terms, not ours. Without the veil, we would lose that precious insulation which would constantly interfere with our mortal probation and maturation. Without the veil, our brief mortal walk in a darkening world would lose its meaning—for one would scarcely carry the flashlight of faith at noonday and in the presence of the Light of the World. Without the veil, we could not experience the gospel of work and the sweat of our brow. If we had the security of having already entered into God‘s rest, certain things would be unneeded; Adam and Eve did not clutch social security cards in the Garden of Eden.

And how could we learn about obedience if we were shielded from the consequences of our disobedience? And how could we learn patience under pressure if we did not experience pressure and waiting? Nor could we choose for ourselves if we were already in His holy presence, for some alternatives do not there exist. Besides, God’s Court is filled with those who have patiently overcome—whose company we do not yet deserve.

Fortunately, the veil keeps the first, second, and third estates separate—hence our sense of separateness. The veil avoids having things “compound in one” to our everlasting detriment (2 Nephi 2:11). We are cocooned, as it were, in order that we might truly choose. Once, long ago, we chose to come to this very setting where we could choose. It was an irrevocable choice. And the veil is the guarantor that our ancient choice will be honored.

When the veil which encloses us is no more, time will also be no more (D&C 84:100). Even now, time is clearly not our natural dimension. Thus it is that we are never really at home in time. Alternately, we find ourselves impatiently wishing to hasten the passage of time or to hold back the dawn. We can do neither, of course. Whereas the bird is at home in the air, we are clearly not at home in time—because we belong to eternity. Time, as much as any one thing, whispers to us that we are strangers here. If time were natural to us, why is it that we have so many clocks and wear wristwatches?

Thus the veil stands—not to shut us out forever, but to remind us of God’s tutoring and patient love for us. Any brush against the veil produces a feeling of “not yet,” but also faint whispers of anticipation of that moment when, in the words of today‘s choral hymn, “Come, Let Us Anew,” those who have prevailed “by the patience and hope and the labor of love” will hear the glorious words,” ‘Well and faithfully done; / Enter into my joy and sit down on my throne’ “ (Hymns, number 17).

May each of us live for that special moment patiently and righteously, I pray in the name of Him who is so patient with me as I strive to be an “especial witness” for him in all the world, even Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

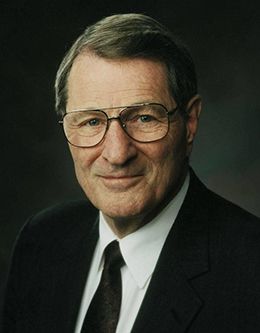

Neal A. Maxwell was a President of the First Quorum of the Seventy of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 27 November 1979.