From the time I started the first grade, the early fall season has always held a special fascination for me because it marks the beginning of a new school term. And now it’s here again, carrying the same set of pleasant reactions. With you, I look forward to this school year. For some of you this will be your first BYU experience, others are just returning from missions, and for many the next few months will be your last at BYU. But for all of us the year holds great promise, and, like you, I look forward to it.

I want to talk to you today about three words that begin with the letter e: education, environment, and etiquette.

The value of education is that, if properly done, it leads to learning, which is one of life’s most intriguing processes. Learning can happen in organized, systematic ways with carefully planned classes and curricula. And that’s what BYU is all about. I still remember my own experiences on this campus as a student years ago when I learned from inspiring teachers who opened my eyes, my mind, and my spirit to new corners of knowledge. Some of the information that I gained during those times I have continued to use over the years. But most interesting of all was the learning process, the acquisition of new information, and the gaining of new insights.

Learning can also happen in unexpected ways. Let me tell you of my own recent experience.

Last May Janet and I spent some time with the Young Ambassadors as they toured the Soviet Union. One morning in the town of Yaraslavl, when we went out for a morning jog, it occurred to me that we would be in real trouble if we got lost. On more than one occasion I have lost my way when I’ve jogged in a strange town. But it could be a serious problem in a place where we didn’t speak a word of the language. My solution, a very logical one, was to memorize the name of our hotel. So, as we left that morning, I saw in big letters across the entrance to our hotel the following letters: P-E-C-T-O-P-A-H.

Pectopah. I promptly committed the word to memory, and Janet and I left on our sojourn through Yaraslavl confident in the fact that we had an effective safety valve. If we got lost, I would just put on my best inquisitive demeanor, give the name of our hotel, and follow the hand signal directions we would be given.

Fortunately, we did not get lost, and so I had no need to ask anybody how to get to the Hotel Pectopah. But the next day, in Moscow, I began to notice that same word, again in very prominent letters, across the awnings in front of many of the buildings that I saw. At first I concluded that it must be a chain. Hotels have been named for people like Willard Marriott and Conrad Hilton. Maybe these were in honor of someone named Anatoly or Boris Pectopah. But further observation revealed that my now favorite Russian word (indeed, other than “spaciva,” which means thank you, my only word) appeared on establishments that quite clearly could not be hotels. So I asked President Gary Browning, who, when he is not serving as mission president in that part of the world teaches Russian at BYU, what my word really meant. His answer: “Restaurant.” The Cyrillic alphabet’s p sounds like our r. The c’s are always s’s, and the h’s aren’s. And so it isn’t Pectopah at all. It’s restoran.

I had several reactions to that simple little experience. First, I realized that if we had lost our way that morning, Janet and I would still be wandering around the city of Yaraslavl, where by now we would probably be famous as those crazy people who speak a language that consists of only two words: Hotel Pectopah. Second, I had come up with a rather nice English/Russian cognate: restoran, restaurant. But most important of all, the experience stirred my curiosity, and I started looking for some other words that perhaps I could recognize. The next one, frankly, was easy, because of the logo that appeared right underneath it. Here is the word that I saw: ПЕПСИ. Not so easy, you say? Well, let me show you the logo, and you will see why it was easy. Obviously, the word was Pepsi.

That one, for me, was the real break-through. Substantively, it added only two letters to my growing bundle of knowledge. The Greek letter pi, which is the first letter and the third, is a p, and the backwards n at the end is a vowel that sounds something like our double e. And I could figure that out from the fact that I knew it was Pepsi. But this gave me just enough—partly in information, but more important, in desire to know—to start me looking for all the cognates I could find. There are not, incidentally, very many; indeed, the count is minuscule if compared to Spanish, the one foreign language that I know something about. But my sense of satisfaction and accomplishment grew as I began recognizing words like Pravda, Kremlin, sport, and two very common ones,gastronome and product, both of which, I am told, are roughly equivalent to our word for groceries. Here is a nice one that you should now be able to figure out: РЕКС. That’s right, it’s my first name.

Interestingly enough, my greatest satisfaction came from this four-letter word: СТОП. You now have enough information (because I’m sure you’ve all been carefully following everything I’ve said) to pronounce that word. Moreover, it’s short and fairly easy. And the only place that I saw it was on traffic lights. But I said to myself, “That just can’t be. That would make it not just a cognate, but the identical English word.” And that, President Browning informed me, is exactly what it is. The word is stop, S-T-O-P, and it is the same in Russian as in English. Same meaning, same usage, and same four-letter spelling—I assume because they borrowed it from us as a total package.

At one level, what I have just recounted can be viewed as a trivial series of events—of passing interest to me at the time they occurred, but having no lasting value to you or me or anyone else. For the rest of my life, the stop signs with which I will deal will have markings other than the ones I saw in Moscow. But I wish I could tell you how enthused I became each time one of those seemingly inconsequential events unfolded. The reason was, I was learning something—something entirely new—and I believe that learning as a process has its rewards wholly aside from the substance of the thing learned. These occurrences were similar to other experiences that I have had at other times in my life as I have delved into new subjects or discovered new applications or significances to existing ones.

Some of these have involved the scriptures. I remember how excited I became when several years ago I saw for the first time evidence in the book of Alma that a rule of constitutional law, which represents fifty years of evolving United States Supreme Court jurisprudence and was finally settled in the late 1960s by a case called Brandenburg v. Ohio, had actually been set forth with rather astounding clarity over 2,000 years earlier in the thirtieth chapter of Alma, which gives an account that lawyers might characterize as City of Zarahemla v. Korihor. Another such experience occurred just last January, when I saw for the first time some implications of the Eleventh Amendment to the United States Constitution that I had never before perceived, notwithstanding years of teaching, reading, and arguing Supreme Court cases involving that particular provision of the Constitution. The same thing can happen when I read good books, when I help my daughter with her math, or in an almost endless variety of activities. Janet’s recounting of the satisfaction our son Tom felt when he finally learned to write his name so it didn’t say “MOT” is a classic example.

The opportunities for learning are all around us, and when those opportunities materialize, we always have a sense of accomplishment and joy. Two weeks ago, Bishop Eyring, in an address to our faculty, staff, and administrators, said of his father, Henry Eyring, who was a scientist of international repute: “He took delight in what he didn’t know, because he saw no limits to what he could learn.”

There are many other things that we could discuss about education, but I’m going to leave you with just that one and move on to my other two e’s,environment and etiquette. As applied to us, there is a strong tie between the two.

The physical environment at BYU is as pleasant and as conducive to living and learning as you will find anywhere. Visitors to our university uniformly comment on it. In part, the attractiveness of our physical surroundings is due to the outstanding work by the many people, including hundreds of students, who care so meticulously for our buildings and grounds.

But our BYU environment consists of more than green lawns and clean buildings. The people are also part of it, especially the students. Ours is a campus where cleanliness, modesty, orderliness, and general physical appearance count for something. They are important to all of us—important enough that we should put forth some effort to maintain them.

Our honor code and dress and grooming standards are an integral and essential part of this unique environment. They in fact involve more than just environmental considerations. They are anchored in principles of morality and good citizenship. Some of those moral principles are found in revealed truth, such as our sexual morality and Word of Wisdom standards. Others are based on considerations of cleanliness, modesty, and general appearance, but all are grounded in morals, because they are standards that we committed to keep as a condition of our being here, and keeping commitments is a moral issue of the highest order.

One of this coming year’s activities for which I have the highest hopes is the plan of your student leaders to provide opportunities for all of us to come to a fuller appreciation of why these honor code and dress and grooming standards are such an integral part of what makes BYU what it is. It is my fervent hope that we can all develop not only an understanding, but also a feeling of ownership—that is, a shared stake—in the success of our honor code.

My final e is etiquette, and it relates to how we treat other people. Every day on this campus there are literally tens of thousands of opportunities for someone to be nice to someone else, or to be not so nice—either to put into practice or to ignore our Savior’s most fundamental of all admonitions to be concerned about other people and their welfare and happiness and not just our own. Truly, that admonition is central not only to Christianity and restored truth, but also to human happiness. I am sure that its centrality to human happiness is the reason the Savior made it the cornerstone of his teachings.

Frankly, I think that with three times as many people on this campus as when I was here as a student, we may have to work at it three times as hard. But I believe it is worth doing. The etiquette to which I refer—a Christ-like niceness, concern—of course includes the maintenance of our environment, including keeping our campus clean and observing the Honor Code and dress and grooming standards. But it also includes elementary principles of Christian living. I can think of no better lesson that all of us could learn from our experience at BYU than the importance of genuinely caring for our neighbor. We have so many opportunities for that here—in the classroom, in our private learning efforts, and in preserving our BYU environment, which is unlike any other.

These three values that begin with e (education, environment, and etiquette) constitute the tissue of life at BYU. Education is our business, though our scope is broader than at other institutions, and is concerned with the total soul and not just the mind.

A headline in yesterday’s Universe said, “BYU is not so unique after all.” The support for this proposition w as that there are other universities that are also founded on religious values. Of course there are, but that fact is irrelevant to our uniqueness. We yield to no one in our respect and our admiration for the strong values, including religiously based values, held by many of our sister institutions. And we of course share many of those same values. Those religious schools help us, and we help them. But those similarities will never make us the same. BYU will always be different—and therefore unique—for the same reasons that the restored kingdom of Jesus Christ is different from other churches and religious endeavors. By definition, there is and can be only one restoration of all things in this dispensation. And only one four-year university is anchored to that restoration. Is it true then that BYU is “not so unique after all”? It is not. Absolutely, we are unique—not in the sense of having a value system or a religious value system, but the principles on which we are built are the principles of restored truth, and they are unique to us for the simple reason that the restored gospel itself is in a class alone. I am grateful that we share values with other universities. I am also grateful that our package has some elements of our own that set us apart from all others.

Finally, I want to tell you how proud I am of you and how honored I am to count myself among your number. Pride can be a serious defect, but not, I think, the kind that I feel for the overwhelming majority of our students. It thrills me to contemplate the great leadership and other strengths that you represent as part of the restored kingdom of Jesus Christ. We have so much to give, and we can give more abundantly. I look forward to joining hands with you in this endeavor, both over the coming school year as well as in the years ahead. That we may do it well is my prayer, in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

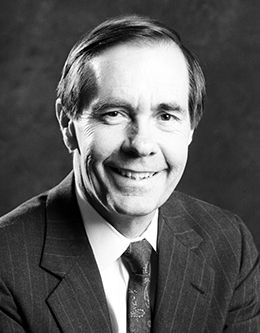

Rex E. Lee was president of Brigham Young University when this devotional address was given on 10 September 1991.