The Second Century of Brigham Young University

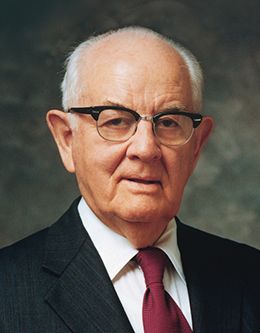

President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

October 10, 1975

President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

October 10, 1975

As previous First Presidencies have said, and we say again to you, we expect (we do not simply hope) that Brigham Young University will “become a leader among the great universities of the world.” To that expectation I would add, “Become a unique university in all of the world.”

My beloved brothers and sisters: It was almost eight years ago that I had the privilege of addressing an audience at the Brigham Young University about “Education for Eternity.”1 Some things were said then that I believe, then and now, about the destiny of this unique university. I shall refer to several of those ideas again, combining them with some fresh thoughts and impressions I have concerning Brigham Young University as it enters its second century.

I am grateful to all who made possible the Centennial Celebration for the Brigham Young University, including those who have developed the history of this university in depth. A centennial observance is appropriate, not only to renew our ties with the past but also to review and reaffirm our goals for the future. My task is to talk about BYU’s second century. Though my comments will focus on Brigham Young University, it is obvious to all of us here that the university is, in many ways, the center of the Church Educational System. President David O. McKay described the university as “the hub of the Church educational wheel.”2 Karl G. Maeser described Brigham Young Academy as “the parent trunk of a great educational banyan tree,”3 and recently it has been designated “the flagship.”4 However it is stated, the centrality of this university to the entire system is a very real fact of life. What I say to you, therefore, must take note of things beyond the borders of this campus but not beyond its influence. We must ever keep firmly in mind the needs of those ever-increasing numbers of Latter-day Saint youth in other places in North America and in other lands who cannot attend this university, whose needs are real, and who represent, in fact, the majority of Latter-day Saint college and university students.

In a speech I gave to many of the devoted alumni of this university in the Arizona area, I employed a phrase to describe the Brigham Young University as becoming an “educational Everest.” There are many ways in which BYU can tower above other universities—not simply because of the size of its student body or its beautiful campus but because of the unique light BYU can send forth into the educational world. Your light must have a special glow, for while you will do many things in the programs of this university that are done elsewhere, these same things can and must be done better here than others do them. You will also do some special things here that are left undone by other institutions.

First among these unique features is the fact that education on this campus deliberately and persistently concerns itself with “education for eternity,” not just for time. The faculty has a double heritage that they must pass along: the secular knowledge that history has washed to the feet of mankind along with the new knowledge brought by scholarly research, and also the vital and revealed truths that have been sent to us from heaven.

This university shares with other universities the hope and the labor involved in rolling back the frontiers of knowledge even further, but we also know that through the process of revelation there are yet “many great and important things”5 to be given to mankind that will have an intellectual and spiritual impact far beyond what mere men can imagine. Thus, at this university, among faculty, students, and administration, there is and must be an excitement and an expectation about the very nature and future of knowledge that underwrites the uniqueness of BYU.

Your double heritage and dual concerns with the secular and the spiritual require you to be “bilingual.” As scholars you must speak with authority and excellence to your professional colleagues in the language of scholarship, and you must also be literate in the language of spiritual things. We must be more bilingual, in that sense, to fulfill our promise in the second century of BYU.

BYU is being made even more unique, not because what we are doing is changing but because of the general abandonment by other universities of their efforts to lift the daily behavior and morality of their students.

From the administration of BYU in 1967 came this thought:

[Brigham Young] University has been established by the prophets of God and can be operated only on the highest standards of Christian morality. . . . Students who instigate or participate in riots or open rebellion against the policies of the university cannot expect to remain at the university.

. . . The standards of the Church are understood by students who have been taught these standards in the home and at church throughout their lives.

First and foremost, we expect BYU students to maintain a single standard of Christian morality. . . .

. . . Attendance at BYU is a privilege and not a right[,] and . . . students who attend must expect to live its standards or forfeit the privilege.6

We have no choice at BYU except to “hold the line” regarding gospel standards and values and to draw men and women from other campuses also—all we can—into this same posture, for people entangled in sin are not free. At this university (that may to some of our critics seem unfree) there will be real individual freedom. Freedom from worldly ideologies and concepts unshackles man far more than he knows. It is the truth that sets men free. BYU, in its second century, must become the last remaining bastion of resistance to the invading ideologies that seek control of curriculum as well as classroom. We do not resist such ideas because we fear them but because they are false. BYU, in its second century, must continue to resist false fashions in education, staying with those basic principles that have proved right and have guided good men and women and good universities over the centuries. This concept is not new, but in the second hundred years we must do it even better.

When the pressures mount for us to follow the false ways of the world, we hope in the years yet future that those who are part of this university and the Church Educational System will not attempt to counsel the board of trustees to follow false ways. We want, through your administration, to receive all your suggestions for making BYU even better. I hope none will presume on the prerogatives of the prophets of God to set the basic direction for this university. No man comes to the demanding position of the presidency of the Church except his heart and mind are constantly open to the impressions, insights, and revelations of God. No one is more anxious than the Brethren who stand at the head of this Church to receive such guidance as the Lord would give them for the benefit of mankind and for the people of the Church. Thus, it is important to remember what we have in the revelations of the Lord: “And thou shalt not command him who is at thy head, and at the head of the church.”7 If the governing board has as much loyalty from faculty and students, from administration and staff as we have had in the past, I do not fear for the future!

The Church Board of Education and the Brigham Young University Board of Trustees involve individuals who are committed to truth as well as to the order of the kingdom. I observed while I was here in 1967 that this institution and its leaders should be like the Twelve as they were left in a very difficult world by the Savior:

The world hath hated them, because they are not of the world, even as I am not of the world.

I pray not that thou shouldest take them out of the world, but that thou shouldest keep them from the evil.

They are not of the world, even as I am not of the world.8

This university is not of the world any more than the Church is of the world, and it must not be made over in the image of the world.

We hope that our friends, and even our critics, will understand why we must resist anything that would rob BYU of its basic uniqueness in its second century. As the Church’s commissioner of education said on the occasion of the inaugural of President Dallin H. Oaks:

Brigham Young University seeks to improve and “sanctify” itself for the sake of others—not for the praise of the world, but to serve the world better.9

That task will be persisted in. Members of the Church are willing to doubly tax themselves to support the Church Educational System, including this university, and we must not merely “ape the world.” We must do special things that would justify the special financial outpouring that supports this university.

As the late President Stephen L Richards once said, “Brigham Young University will never surrender its spiritual character to sole concern for scholarship.” BYU will be true to its charter and to such addenda to that charter as are made by living prophets.

I am both hopeful and expectant that out of this university and the Church Educational System there will rise brilliant stars in drama, literature, music, sculpture, painting, science, and in all the scholarly graces. This university can be the refining host for many such individuals who will touch men and women the world over long after they have left this campus.

We must be patient, however, in this effort, because just as the city of Enoch took decades to reach its pinnacle of performance in what the Lord described as occurring “in process of time,”10 so the quest for excellence at BYU must also occur “in process of time.”

Ideals are like stars; you will not succeed in touching them with your hands. But like the seafaring man on the desert of waters, you choose them as your guides, and following them you will reach your destiny.11

I see even more than was the case nearly a decade ago a widening gap between this university and other universities, both in terms of purposes and in terms of directions. Much has happened in the intervening eight years to make that statement justifiable. More and more is being done, as I hoped it would, to have here “the greatest collection of artifacts, records, writings . . . in the world.”12 BYU is moving toward preeminence in many fields, thanks to the generous support of the tithe payers of the Church and the excellent efforts of its faculty and students under the direction of a wise administration.

These changes do not happen free of pain, challenge, and adjustment. Again, harking back, I expressed the hope that the BYU vessel would be kept seaworthy by taking “out all old planks as they decay and put[ting] in new and stronger timber in their place,” because the Flagship BYU “must sail on and on and on.”13 The creative changes in your academic calendar, your willingness to manage your curriculum more wisely, your efforts to improve general education, your interaction of disciplines across traditional departmental lines, and the creation of new research institutes here on this campus—all are evidences that the captain and crew are doing much to keep the BYU vessel seaworthy and sailing. I refer to the centers of research that have been established on this campus, ranging from family and language research on through to research on food, agriculture, and ancient studies. Much more needs to be done, but you must “not run faster or labor more than you have strength and means provided.”14 While the discovery of new knowledge must increase, there must always be a heavy and primary emphasis on transmitting knowledge—on the quality of teaching at BYU. Quality teaching is a tradition never to be abandoned. It includes a quality relationship between faculty and students. Carry these over into BYU’s second century!

Brigham Young undoubtedly meant both teaching and learning when he said:

Learn everything that the children of men know, and be prepared for the most refined society upon the face of the earth, then improve upon this until we are prepared and permitted to enter the society of the blessed—the holy angels that dwell in the presence of God.15

We must be certain that the lessons are not only taught but are also absorbed and learned. We remember the directive that Karl G. Maeser made to President John Taylor “that no infidels will go from my school.”16

[To the founders of what is today known as Snow College, President Taylor said:] Whatever you do, be choice in your selection of teachers. We do not want infidels to mould the minds of our children. They are a precious charge bestowed upon us by the Lord, and we cannot be too careful in rearing and training them. I would rather have my children taught the simple rudiments of a common education by men of God, and have them under their influence, than have them taught in the most abstruse sciences by men who have not the fear of God in their hearts. . . . We need to pay more attention to educational matters, and do all we can to procure the services of competent teachers. Some people say, we cannot afford to pay them. You cannot afford not to pay them; you cannot afford not to employ them. We want our children to grow up intelligent, and to walk abreast with the peoples of any nation. God expects us to do it; and therefore I call attention to this matter. I have heard intelligent practical men say, it is quite as cheap to keep a good horse as a poor one, or to raise good stock as inferior animals. And is it not quite as cheap to raise good intelligent children as to rear children in ignorance.17

Thus, we can continue to do as the Prophet Joseph Smith implied that we should when he said, “Man was created to dress the earth, and to cultivate his mind, and glorify God.”18

We cannot do these things except we continue, in the second century, to be concerned about the spiritual qualities and abilities of those who teach here. In the book of Mosiah we read, “Trust no one to be your teacher nor your minister, except he be a man of God, walking in his ways and keeping his commandments.”19 William R. Inge said, “I have no fear that the candle lighted in Palestine . . . years ago will ever be put out.”20

We must be concerned with the spiritual worthiness, as well as the academic and professional competency, of all those who come here to teach. William Lyon Phelps said:

I thoroughly believe in a university education for both men and women; but I believe a knowledge of the Bible without a college course is more valuable than a college course without the Bible.21

Students in the second century must continue to come here to learn. We do not apologize for the importance of students searching for eternal companions at the same time that they search the scriptures and search the shelves of libraries for knowledge. President McKay observed on one occasion that

a university is not a dictionary, a dispensary, nor is it a department store. It is more than a storehouse of knowledge and more than a community of scholars. University life is essentially an exercise in thinking, preparing, and living.22

We do not want BYU ever to become an educational factory. It must concern itself with not only the dispensing of facts but with the preparation of its students to take their place in society as thinking, thoughtful, and sensitive individuals who, in paraphrasing the motto of your centennial, come here dedicated to love of God, pursuit of truth, and service to mankind.

There are yet other reasons why we must not lose either our moorings or our sense of direction in the second century. We still have before us the remarkable prophecy of John Taylor when he observed:

You will see the day that Zion will be as far ahead of the outside world in everything pertaining to learning of every kind as we are today in regard to religious matters. You mark my words, and write them down, and see if they do not come to pass.23

Surely we cannot refuse that rendezvous with history because so much of what is desperately needed by mankind is bound up in our being willing to contribute to the fulfillment of that prophecy. Others, at times, also seem to have a sensing of what might happen. Charles H. Malik, former president of the United Nations General Assembly, voiced a fervent hope when he said that

one day a great university will arise somewhere . . . I hope in America . . . to which Christ will return in His full glory and power, a university which will, in the promotion of scientific, intellectual, and artistic excellence, surpass by far even the best secular universities of the present, but which will at the same time enable Christ to bless it and act and feel perfectly at home in it.24

Surely BYU can help to respond to that call!

By dealing with basic issues and basic problems, we can be effective educationally. Otherwise, we will simply join the multitude who have so often lost their way in dark, sunless forests even while working hard. It was Thoreau who said, “There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root.”25 We should deal statistically and spiritually with root problems, root issues, and root causes in BYU’s second century. We seek to do so, not in arrogance or pride but in the spirit of service. We must do so with a sense of trembling and urgency because what Edmund Burke said is true: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.”26

Learning that includes familiarization with facts must not occur in isolation from concern over our fellowmen. It must occur in the context of a commitment to serve them and to reach out to them.

In many ways the dreams that were once generalized as American dreams have diminished and faded. Some of these dreams have now passed so far as institutional thrust is concerned to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its people for their fulfillment. It was Lord Acton who said on one occasion:

It was from America that the plain ideas that men ought to mind their own business, and that the nation is responsible to Heaven for the acts of the State—ideas long locked in the breast of solitary thinkers, and hidden among Latin folios—burst forth like a conqueror upon the world they were destined to transform, under the title of the Rights of Man. . . .

. . . And the principle gained ground, that a nation can never abandon its fate to an authority it cannot control.27

Too many universities have given themselves over to such massive federal funding that they should not wonder why they have submitted to an authority they can no longer control. Far too many no longer assume that nations are responsible to heaven for the acts of the state. Far too many now see the Rights of Man as merely access rights to the property and money of others, and not as the rights traditionally thought of as being crucial to our freedom.

It will take just as much sacrifice and dedication to preserve these principles in the second century of BYU—even more than that required to begin this institution in the first place, when it was once but a grade school and then an academy supported by a stake of the Church. If we were to abandon our ideals, would there be any left to take up the torch of some of the principles I have attempted to describe?

I am grateful, therefore, that, as President Oaks observed, “There is no anarchy of values at Brigham Young University.”28 There never has been. There never will be. But we also know, as President Joseph Fielding Smith observed in speaking on this campus, that “knowledge comes both by reason and by revelation.”29 We expect the natural unfolding of knowledge to occur as a result of scholarship, but there will always be that added dimension that the Lord can provide when we are qualified to receive and He chooses to speak:

A time to come in the which nothing shall be withheld, whether there be one God or many gods, they shall be manifest.

And further,

All thrones and dominions, principalities and powers, shall be revealed and set forth upon all who have endured valiantly for the gospel of Jesus Christ.30

As the pursuit of excellence continues on this campus and elsewhere in the Church Educational System, we must remember the great lesson taught to Oliver Cowdery, who desired a special outcome—just as we desire a remarkable blessing and outcome for BYU in the second century. Oliver Cowdery wished to be able to translate with ease and without real effort. He was reminded that he erred, in that he “took no thought save it was to ask.”31 We must do more than ask the Lord for excellence. Perspiration must precede inspiration; there must be effort before there is excellence. We must do more than pray for these outcomes at BYU, though we must surely pray. We must take thought. We must make effort. We must be patient. We must be professional. We must be spiritual. Then, in the process of time, this will become the fully anointed university of the Lord about which so much has been spoken in the past.

We can sometimes make concord with others, including scholars who have parallel purposes. By reaching out to the world of scholars, to thoughtful men and women everywhere who share our concerns and at least some of the items on our agenda of action, we can multiply our influence and give hope to others who may assume that they are alone.

In other instances, we must be willing to break with the educational establishment (not foolishly or cavalierly, but thoughtfully and for good reason) in order to find gospel ways to help mankind. Gospel methodology, concepts, and insights can help us to do what the world cannot do in its own frame of reference.

In some ways the Church Educational System, in order to be unique in the years that lie ahead, may have to break with certain patterns of the educational establishment. When the world has lost its way on matters of principle, we have an obligation to point the way. We can, as Brigham Young hoped we would, “be a people of profound learning pertaining to the things of the world,”32 but without being tainted by what he regarded as “the pernicious, atheistic influences”33 that flood in unless we are watchful. Our scholars, therefore, must be sentries as well as teachers!

We surely cannot give up our concerns with character and conduct without also giving up on mankind. Much misery results from flaws in character, not from failures in technology. We cannot give in to the ways of the world with regard to the realm of art. President Marion G. Romney brought to our attention not long ago a quotation in which Brigham Young said that “there is no music in hell.”34 Our art must be the kind that edifies man, that takes into account his immortal nature, and that prepares us for heaven, not hell.

One peak of educational excellence that is highly relevant to the needs of the Church is the realm of language. BYU should become the acknowledged language capital of the world in terms of our academic competency and through the marvelous “laboratory” that sends young men and women forth to service in the mission field. I refer, of course, to the Language Training Mission. There is no reason why this university could not become the place where, perhaps more than anywhere else, the concern for literacy and the teaching of English as a second language is firmly headquartered in terms of unarguable competency as well as deep concern.

I have mentioned only a few areas. There are many others of special concern, with special challenges and opportunities for accomplishment and service in the second century.

We can do much in excellence and, at the same time, emphasize the large-scale participation of our students, whether it be in athletics or in academic events. We can bless many and give many experience while, at the same time, we are developing the few select souls who can take us to new heights of attainment.

It ought to be obvious to you, as it is to me, that some of the things the Lord would have occur in the second century of BYU are hidden from our immediate view. Until we have climbed the hill just before us, we are not apt to be given a glimpse of what lies beyond. The hills ahead are higher than we think. This means that accomplishments and further direction must occur in proper order, after we have done our part. We will not be transported from point A to point Z without having to pass through the developmental and demanding experiences of all the points of achievement and all the milestone markers that lie between!

This university will go forward. Its students are idealists who have integrity, who love to work in good causes. These students will not only have a secular training but will have come to understand what Jesus meant when He said that the key of knowledge, which had been lost by society centuries before, was “the fulness of [the] scriptures.”35 We understand, as few people do, that education is a part of being about our Father’s business and that the scriptures contain the master concepts for mankind.

We know there are those of unrighteous purposes who boast that time is on their side. So it may seem to those of very limited vision. But of those engaged in the Lord’s work, it can be truly said, “Eternity is on our side! Those who fight that bright future fight in vain!”

I hasten to add that as the Church grows global and becomes more and more multicultural, a smaller and smaller percentage of all our Latter-day Saint college-age students will attend BYU or the Hawaii Campus or Ricks College or the LDS Business College. It is a privileged group who are able to come here. We do not intend to neglect the needs of the other Church members wherever they are, but those who do come here have an even greater follow-through responsibility to make certain that the Church’s investment in them provides dividends through service and dedication to others as they labor in the Church and in the world elsewhere.

To go to BYU is something special. There were Brethren who had dreams regarding the growth and maturity of Brigham Young University, even to the construction of a temple on the hill they had long called Temple Hill, yet “dreams and prophetic utterances are not self-executing. They are fulfilled only by righteous and devoted people making the prophecies come true.”36

So much of our counsel given to you here today as you begin your second century is the same counsel we give to others in the Church concerning other vital programs—you need to lengthen your stride, quicken your step, and (to use President N. Eldon Tanner’s phrase) continue your journey. You are headed in the right direction! Such academic adjustments as need to be made will be made out of the individual and collective wisdom we find when a dedicated faculty interacts with a wise administration, an inspired governing board, and an appreciative body of students.

I am grateful that the Church can draw upon the expertise that exists here. The pockets of competency that are here will be used by the Church increasingly and in various ways.

We want you to keep free as a university—free of government control, not only for the sake of the university and the Church but also for the sake of our government. Our government, state and federal, and our people are best served by free colleges and universities, not by institutions that are compliant out of fears over funding.

We look forward to developments in your computer-assisted translation projects and from the Ezra Taft Benson Agriculture and Food Institute. We look forward to more being done in the field of education, in the fine arts, in the J. Reuben Clark Law School, in the Graduate School of Management, and in the realm of human behavior.

We appreciate the effectiveness of the programs here, such as our Indian program with its high rate of completion for Indian students. But we must do better in order to be better, and we must be better for the sake of the world!

As previous First Presidencies have said, and we say again to you, we expect (we do not simply hope) that Brigham Young University will “become a leader among the great universities of the world.”37 To that expectation I would add, “Become a unique university in all of the world!”

May I thank now all those who have made this Centennial Celebration possible and express appreciation to the alumni, students, and friends of the university for the Centennial Carillon Tower that is being given to the university on its one hundredth birthday. Through these lovely bells will sound the great melodies that have motivated the people of the Lord’s church in the past and will lift our hearts and inspire us in the second century—with joy and even greater determination. This I pray in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

Our Father in Heaven, we are grateful for this, the gift of thy people, the alumni, the faculty, the staff, and the friends of Brigham Young University, for this collection of fifty-two bells in this carillon tower on the campus of this, Thy great university.

We are grateful for the faithfulness and craftsmanship of those who constructed the bells, those who have transported them, and those who have placed them into the tower.

Father, we are grateful for the diversity of the bells in their size, versatility, and music-giving tones, for the clavier and the clappers and the magnetic tape and the keyboard, and we ask Thee, O Father, to protect this tower, these bells, and all pertaining to them, and we pray that the carillonneur will have the preciseness and the ability to create beautiful music from the bells in this tower.

Father, we thank Thee for this institution and what it has meant in the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and their posterity, for the truths they have learned here, for the characters that have been built, for the families that have been strengthened here. Let Thy Spirit continue to be with the president of this institution and his associates, the faculty, the students, alumni, staff, and friends of this university and their successors that Thy Spirit may always abide here and that stalwarts may emerge from this institution to bring glory to Thee and blessings to the people of this world.

Just as these bells will lift the hearts of the hearers when they hear the hymns and anthems played to Thy glory, let the morality of the graduates of this university provide the music of hope for the inhabitants of this planet. We ask that all those everywhere who open their ears to hear the sounds of good music will also be more inclined to open their ears to hear the good tidings brought to us by Thy Son.

Now, dear Father, let these bells ring sweet music unto Thee. Let the everlasting hills take up the sound, let the mountains shout for joy and the valleys cry aloud, and let the seas and dry lands tell the wonders of the Eternal King.

Let the rivers and the brooks flow down with gladness; let the sun, the moon, and the stars sing together and let the whole creation sing the glory of our Redeemer forevermore.

Now, our Father, we dedicate this carillon tower, the bells, the mechanical effects and equipment, and all pertaining to this compound and ask Thee that Thou wouldst bless it and protect it against all destructive elements. Bless it that it may give us sweet music and that because of it we may love and serve Thee even more.

In the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

© by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Notes

1. See Spencer W. Kimball, “Education for Eternity,” pre-school address to BYU faculty and staff, 12 September 1967.

2. See also Ernest L. Wilkinson, ed., Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years, 4 vols. (Provo: BYU Press, 1975–76), 2:573.

3. Karl G. Maeser, in Alma P. Burton, Karl G. Maeser: Mormon Educator (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1953), 73.

4. Marion G. Romney, “Why the J. Reuben Clark Law School?” dedicatory address and prayer of the J. Reuben Clark Law School Building, 5 September 1975.

5. Articles of Faith 1:9.

6. Ernest L. Wilkinson, “A Letter to Parents,” July 1967, 2, 8; see also excerpt of letter in Wilkinson, “Welcome Address,” BYU devotional address, 21 September 1967.

7. Doctrine and Covenants 28:6.

8. John 17:14–16.

9. Neal A. Maxwell, “Greetings to the President,” Addresses Delivered at the Inauguration of Dallin Harris Oaks, 12 November 1971 (Provo: BYU Press, 1971), 1.

10. Moses 7:21.

11. Carl Schurz, address in Faneuil Hall, Boston, 18 April 1859.

12. Kimball, “Education for Eternity.”

13. Kimball, “Education for Eternity.”

14. Doctrine and Covenants 10:4.

15. Brigham Young, JD 16:77 (25 May 1873).

16. Karl G. Maeser, quoted in John Taylor, JD 20:48 (4 August 1878).

17. John Taylor, JD 24:168–69 (19 May 1883).

18. Joseph Smith, “Selections: Cultivate the Mind,” Evening and Morning Star 1, no. 1 (June 1832): 8.

19. Mosiah 23:14.

20. William R. Inge, Christian Ethics and Modern Problems (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1930), 394.

21. William Lyon Phelps, Human Nature in the Bible (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1922), ix.

22. David O. McKay, “A Message for LDS College Youth,” BYU address, 8 October 1952; also excerpted in McKay, Gospel Ideals (Salt Lake City: Improvement Era, 1953), 436.

23. John Taylor, JD 21:100 (13 April 1879).

24. Charles H. Malik, “Education in Upheaval: The Christian’s Responsibility,” Creative Help for Daily Living 21, no. 18 (September 1970): 10.

25. Henry David Thoreau, Walden (1854), I, “Economy.”

26. Attributed to Edmund Burke.

27. Lord Acton, The History of Freedom and Other Essays (1907), chapter 2.

28. Dallin H. Oaks, “Response,” Addresses Delivered at Inauguration, 12 November 1971, 21.

29. Joseph Fielding Smith, “Educating for a Golden Era of Continuing Righteousness,” BYU campus education week address, 8 June 1971, 2.

30. Doctrine and Covenants 121:28–29.

31. Doctrine and Covenants 9:7.

32. Brigham Young, “Remarks,” Deseret News Weekly, 6 June 1860, 97.

33. Brigham Young, in letter to his son Alfales Young, 20 October 1875.

34. Brigham Young, JD 9:244 (6 March 1862).

35. Doctrine and Covenants 42:15.

36. Ernest L. Wilkinson and W. Cleon Skousen, Brigham Young University: A School of Destiny (Provo: BYU Press, 1976), 876.

37. Harold B. Lee, “Be Loyal to the Royal Within You,” BYU devotional address, 11 September 1973.

Spencer W. Kimball was president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 10 October 1975.