May I begin with an incident from our history which, when I first read it, inflamed me and changed my life. In the 1830s there was a student at Oberlin College whose name was Lorenzo Snow. He was disillusioned with what he saw of religion in general and Christianity in particular. He wrote a letter to his sister who had become a Latter-day Saint, Eliza R. Snow, and confessed his difficulties. She wrote back and invited him to Kirtland. He came. Within a few moments, as I read the story, he was inside the temple, the building which at that time served, as many of you know, more than one purpose. It served all of the fundamental functions of the Church. As he entered, there was a meeting in progress, a small one. Patriarchal blessings were being given by the Prophet’s father, Joseph Smith, Sr. He listened, first incredulous, then open, and toward the end inspired. He kept saying to himself, “Can this be simply a man or is there something divine involved?” He came more and more to feel that the Spirit was in it.

At the end of that, the Prophet’s father took his hand (there had been no introduction as I read it) and, still filled with the light of his calling, said two things to him. “You will become one of us.” Lorenzo Snow understood that but didn’t believe it. But now the blockbuster. “And you will become great—even as great as God is. And you could not wish to become greater.” That, young Lorenzo Snow did not understand. Shortly the first prediction was fulfilled. The story of his conversion, of his baptism, of the overwhelming later experience after a confirmation which he felt left him somewhat stillborn, when he was so immersed by the influences of God that for several nights he could hardly sleep, burning, he says, with a “tangible awareness” of God in a way that changed him—that story there isn’t time for.

Lorenzo Snow’s Revelation About Perfection

But I now move you to a later period in his life. He had served; he had become one of our great and dedicated missionaries. He was sitting discussing the scriptures with a brother in Nauvoo. At that moment something happened to him which in later life he called an impression; sometimes he spoke of it as a vision, sometimes as an overwhelming revelation. He came to glimpse the meaning of what had been said to him. And he formed it in a couplet which we hesitate, all of us, and I think wisely, to cite in discussion or conversation but which is a sacred, glorious insight. It’s a couplet; he put it in faultless rhythm: “As man now is God once was. As God now is man may become.” He says he saw a conduit, as it were, down through which, in fact, by our very nature, by our being begotten of our eternal parents, we descend and up through which we may ascend. It struck him with power that if a prince born to a king will one day inherit his throne, so a son of an eternal father will one day inherit the fullness of his father’s kingdom.

Suddenly he recovered the verses, repeated but without depth, of the New Testament that we are commanded to become perfect; then, lest we should relativize that, the Master had added, “even as your Father.” The verses in 1 John vibrate with his comprehension of love: “Behold, what manner of love the Father hath bestowed upon us, that we should be called the sons of God. . . . Beloved, now are we the sons of God, and it doth not yet appear what we shall be: but we know that, when he shall appear, we shall be like him; for we shall see him as he is” (1 John 3:1–2; emphasis added).

That became a guiding star to young Lorenzo Snow. It went with him through other callings and sacrifices. He hardly dared breathe it—even to his intimates—except to his sister, Eliza, and later during a close missionary discussion with Brother Brigham Young. Not a word had been spoken by the Prophet Joseph specifically giving that principle. But Lorenzo knew it. And you can imagine how he felt when, sitting in the Nauvoo Grove, April 1844, the Prophet Joseph Smith arose and said with power, “God was once a man as we are now.”

Sectarian Concepts of Deity

Now may I take you elsewhere to sympathize for a moment with the outlook others have on this and to understand why it is so sacred and must be kept so. In a discussion at a widely known theological seminary in the East, I was asked, “What is the Mormon understanding of God?” I struggled to testify. Then three of the most learned of their teachers, not with acrimony but with candor, said, “Let us explain why we cannot accept this. First of all, you people talk of God in terms that are human—all too human.” (That’s a phrase, incidentally, from Nietzsche.) “But the second problem is worse. You dare to say that man can become like God.” And they held up a hand and said, “Blasphemy.” Well, that hurts a little. I was led to ask two series of questions. (Mind you, I’m telling you the story. I’m not sure they would tell it the same way. I’ve had a chance to improve it in the interim.)

The first was a series of questions about the nature of Christ. “Was he a person?”

“Yes.”

“Did he live in a certain place and time?”

“Yes.”

“Was he embodied?”

“Yes.”

“Was he somewhere between five and seven feet in height?”

“Well, we hadn’t thought of it, but, yes, we suppose he was.”

“Was he resurrected with his physical body?”

“He was.”

“Does he now have that body?”

“Yes.”

“Will he always?”

“Yes.”

“Is there any reason we should not adore and honor and worship him for what he has now become?”

“No,” they said, “he is very God.”

“Yes,” I said, “what then of the Father?”

“Oh no, oh no.” And then they issued a kind of Platonic manifesto—the statement out of the traditional creeds which are, all due honor to them, more Greek than they are Hebrew. “No, no, the Father is ‘immaterial, incorporeal, beyond space, beyond time, unchanging, unembodied, etc.’”

Now, earlier they had berated me because Mormons, as you know, are credited—or blamed—for teaching, not trinitarianism, but tritheism—the idea of three distinct personages. And I couldn’t resist at that point saying, “Who has two Gods? You are the ones who are saying that there are two utterly unlike persons. The religious dilemma is how can I honor the Father and seek to become like him (for even the pronoun ‘him’ is not appropriate) without become unlike the Christ whom you say we can properly adore and worship and honor.” Well, the attack at that point was that I didn’t understand the Trinity. And I acknowledged that was true.

But now the second set of questions: “Why,” I dared to ask—and it’s a question any child can ask—“did God make us at all?” There’s an answer to that in their catechism. Basically, it is that God did so for his own pleasure and by his inscrutable will. Sometimes it is suggested that he did so that he might have creatures to honor and worship him—which, if we are stark in response, is not the most unselfish motive one could conceive. Sometimes it is said that he did so for our happiness. But because of the creeds it is impossible to say that God needed to do so, for God, in their view, is beyond need. And then the bold question I put was “You hold, don’t you, that God has and had all power, all knowledge, all anticipatory wisdom, and that he knew, therefore, exactly what he was about and could have done otherwise?”

“Yes,” they allowed, “he could.”

“Why then, since God could have created cocreators, did he choose to make us creatures? Why did God choose to make us his everlasting inferiors?”

At that point one of them said, “God’s very nature forbids that he should have peers.”

I replied, “That’s interesting. For us God’s very nature requires that he should have peers. Which God is more worthy of our love?”

Bearing Witness of a Living God

Now, brothers and sisters, prophets have lived and died to reestablish in the world in our generation that glorious truth—that what the Eternal Father wants for you and with you is the fullness of your possibilities. And those possibilities are infinite. And he did not simply make you from nothing into a worm; he adopted and begat you into his likeness in order to share his nature. And he sent his Firstborn Son to exemplify just how glorious that nature can be—even in mortality. That is our witness.

Again and again in recent months I’ve been in circumstances sometimes trying and sometimes inspiring. People want me to answer the question “Are Mormons Christians?” I’ve occasionally reversed it: “Are Christians Mormon?” I have evidence, more and more of it, that there are major spokesmen in all the wings of Christianity and in Judaism who are saying unwittingly today what only the Prophet Joseph Smith was saying 150 years ago.

But one of the discomforts of belonging to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is that occasionally one wonders, “Can I witness to an unbelieving world that I am committed to Jesus Christ in the fullest, richest, highest sense?” Part of my message tonight is to tell you that you can, that you belong to a heritage that testifies that Jesus, the Christ, known for what he was on the morning of his resurrection, is in exact similitude of the highest kind of being in the universe. There is nothing more, nothing higher to be achieved. It is a blasphemy on the part of many beyond the pales of this Church to hold that we are to respect him as simply a kind of man or even a special and endowed and divinely inspired man, but to hold that the nature of God, the highest God, if you will, is something else. I repeat, their concept is not higher; it is always and everywhere lower. To worship “Being” in a static form, to worship an “Unconditioned” without intelligence and will and embodiment, to worship principle, to worship any aspect of the universe or all of it together in preference to the glorified personality who was Jesus Christ is blasphemy. “They seek not the Lord,” said the Lord in his preface to modern revelation, “to establish his righteousness, but every man walketh in his own way, and after the image of his own God, whose image is in the likeness of the world, and whose substance is that of an idol” (D&C 1:16; emphasis added). Is there in the world such an idea of God “in the likeness of the world, and whose substance is that of an idol”? Yes. And we must go on witnessing to a living God—even, paradoxically, if it costs us our lives.

A Sense of Humor and Divine Potential

Now, let me return to two or three implications of this insight for our own nature. I dared to say once to one of our great leaders, “Do you believe God has a sense of humor?”

And without a hesitation he snapped his fingers and said, “Of course. He made you, didn’t he?”

There is something terribly cruel about that. With it I match the psychiatric story of a man who said, “Doctor, I think I have an inferiority complex.”

After some days of psychoanalysis the verdict came out: “No, you’re simply inferior.”

I know, and, having made you laugh, I wish this could go all the way to your marrow, I know that there are on this campus hundreds, thousands, who carry that kind of anchor on their shoulders: “I don’t amount to much. I’m not really one of those good ones.” Or, as a student said to me not too long ago, “I think I’m just basically telestial material.”

What is truth? The truth is, and I bear it humbly, that even the person you think the worst off—and in some cases that may be yourself—even that personality that it has been most difficult for you to forgive will be, in a century or two, in such a condition that if you saw him or her your first impulse would be to kneel in reverence. The truth is that the embryo within the worst of us is divine. The truth is that there is nothing you can do to really destroy that fact. The potential is there.

The Challenges of Church Service and Growth

Now, that leads to a second and more realistic comment in some ways. We live in a church that places tremendous burdens on the laity. We go on asking our nineteen-year-olds to do the impossible. I had a colleague at Harvard who said, “Admit, Madsen, you don’t really seriously send out these boys expecting to make converts, do you? Level with me. Your real purpose is to help them develop a cultural affinity and get some language skill; now isn’t that it? You can’t expect a mere boy to go out in the wild world and make converts.”

I said, “No, I can’t! But the Lord does. And they’re succeeding at the rate of a hundred thousand a year.” Yes.

I’ve noticed that teachers are told (talking about teachers in the Aaronic Priesthood) to see that there is no iniquity in the Church. Strange burden to put on a teenager. We do; the Lord does. And how many of the parents of those of you sitting here tonight are today faithful and alive in the Church because of you and your example? How many parents have been converted by the conversions of their children? How many inactives have been reactivated by the services and faith of their missionary children? How, we don’t know. We don’t realize our own power or the divine burden placed upon us.

Constantly I am astonished to reread the statement made by the Prophet in a setting which I contrast tonight to what we see here. Maybe there were a hundred members of the church then. There were only eight or ten in this particular meeting in a log cabin. Now, the names are names to conjure with. But they weren’t all that great then: Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, Wilford Woodruff, the two Pratts, Orson Hyde. The Prophet said to them, “Please, brethren, bear your witness as to the future of this Church.” It’s 1834. Well, they did so. In my imagination I picture a kind of “Can You Top This?” session. Maybe somebody was daring enough to say that he could foresee the time when there would be fifty thousand Latter-day Saints. When they were all through and had done their best, the Prophet arose and said, “Brethren, I’ve appreciated what you’ve said, but you no more comprehend the destinies of this Church than a little child on its mother’s lap.” That’s strong language to a Brigham Young. And then he said, “Brethren, this Church will fill North and South America. Brethren, this Church will fill the earth.” We don’t read that anyone topped that. That’s true! It is happening under our noses. And when you’re in your prime—let’s just suppose that’s 1990—do you know how many missionaries there will be if we call just the present proportion we’re calling (2 to 3 percent of our membership)? We’ll have seventy-five thousand missionaries! We’ll just be getting started then.

Look, the burden has been placed upon us, and the Lord trusts us even when we don’t fully trust ourselves. The embryo within this student body often keeps me awake at nights. I marvel, I wonder, and I say, “Why can’t we have twenty thousand cheering their hearts out for other things than the last five seconds of a basketball game?” (But I was here shouting last night. I don’t want to suggest that you shouldn’t shout then.) There is a power in unity. And the ultimate unity that the Lord promised and prayed for is again a oneness with him and with the Father, and that requires that we become like them in nature. In very nature. That requires processes which the Lord again and again has compared most constantly to the process of birth and begetting. We are his children; he is our Father. Locked in us, hidden from our present view, are glorious insights and memories, which to know would, for many of us, lead to the neglect of the purposes of this world. We couldn’t stand to stay here, I suspect, if we knew all. I’ve read recently an account, I hope trustworthy, of a brother who says that the Prophet Joseph implied just that—that were it not for the strong biological urge in us to survive, to hold on to the slipping rope even when we’re in pain and suffering, and, in addition to that, were it not for the drawing, the dropping as it were, of the curtain which prevents our gathering from the vineyards of an infinite memory—were it not, in short, for our mortal amnesia, we couldn’t stand it. The shock of leaving that condition and entering this one would be unbearable. We have to stay to work out the possibilities, to undergo the stress and distress that lead to perfection.

Communication with the Living God

Another implication. These brethren and sisters who caught hold in the first generation of the concept of bearing within themselves the very image, the literal image in its entirety, of the living God prayed differently. They did not pray to a God afar off. They did not make amends in some verbal way to a principle. They walked “with Father”—not even saying, “the Father,” but “Father.” All intimacy. All warmth. All trust. And how I have marveled to read the accounts. I’m afraid they’re in contrast to some of the prayers that I myself and perhaps you utter today. My great-grandfather, for example, used to say, “Stay there. Stay on your knees and talk with him [that’s different from talking to him] until you prevail with the Spirit.” He used the image “break the ice”; tear it off and stay on your knees until you’re warm.

Or again, there is the Wilford Woodruff description of the Prophet’s prayers: “Always,” he says, “conversational.” No forced tone of voice, no ostentation, plain, open—the way a trusting child would say his inmost thoughts to a father or mother.

And then there is the description of Heber C. Kimball, the grandfather of our present leader. His biographer, Orson F. Whitney, says of him that “prayers are rarely heard as were heard to issue from the heart and lips of this man.” I was curious why. What did he do differently? Well, I found out. There was first of all a sense of dedication in his home. The home is the second most sacred place in the Church—the first being the temple. (President Lee recently instructed that if you’re not going to be married in the temple, the next best place is home.) They understood that. They dedicated their homes; they dedicated, at times, a room—he did—a special room for prayer. He knew what it was to kneel in silence for a time, to ruminate, to meditate, to recover something of the light in the scriptures and in himself. And then to pray.

He constantly taught his family, and by example demonstrated, that the way to pray is to let out what is really in. For example, he says in a discourse, “When I am angry, the first thing I do is pray. And I am never so angry but what I can’t.” Well, I was taught the exact opposite. If you’re angry you straighten things out, you count to ten, soak your head in a bucket, and when things are all even and you’re composed, then you pray. No. The first thing he did was pray. What, you might ask me, would he say? I don’t know. I can only imagine. But he let it out honestly, openly, in the words that were appropriate. “I’m so angry,” he might have said, “I could spit.” If that’s the way it was, then that’s the way to say it. And there came a return wave, for the Lord honors you when you level, when you stop praying from the neck up and begin praying from way inside, trusting the Spirit to take even the ineptitudes and translate them perfectly, trusting the Lord to know and daring even to voice those particular feelings about which you are most anxious and even guilty, including the prayer which he occasionally offered: “Father in heaven, I just don’t feel like praying.” That’s an honest and powerful prayer. I recommend it.

And then there is the example, lest you suppose there are certain things out of bounds entirely, when he in fact was praying with the family and laughed in the middle. Having named a brother, he burst out laughing. As I have told my wife, I can picture three solutions to that: He might have arisen, left the room with his hand over his mouth, and let his wife pick up the pieces. That’s what I would have done. He could have delivered a very solemn 21/2-minute talk on why we never ever permit a smile in prayer. Or he could have done what he did do. There was a slight pause, and then he said, “I’m sorry, Lord, but I just can’t help laughing when I think about Brother Brown.” And then he went on with his prayer.

Friends not of our faith would say of this, “Blasphemy.” I testify to you, “Beautiful.” Do you think it is a secret to the Lord that you have a funny bone? Do you think that there is wisdom in hiding? And brothers and sisters, be honest. When you testify that the Lord knows your thoughts and feelings, do you believe it? If you were speaking to a loved earthly father and you were in serious trouble, really serious—maybe tragic trouble—but in the middle of the recital if you burst into laughter, maybe a little half-hysterical, would he not understand? Yes, we’re warned against lightmindedness. But what is that? The betrayal, I suggest to you, of sacred things—making light of, ridiculing. That, always and everywhere will deny you the privileges of the Spirit of the Lord. You will be left to yourself if you indulge that kind of lightmindedness. But the Lord nowhere condemns lightheartedness. He commands it. He says that we’re to have “a glad heart and a cheerful countenance” (D&C 59:15) even on fast Sunday when our heads ache and we’re hungry. And he wants us, both in sorrow and in joy, to have the resilient kind of response that humor makes possible. Sometimes life is so ridiculous there is nothing else to do—except laugh.

Thank God we have examples of this in our midst. I wish there were time to mention several, but I’ll just name one. Dear President Brown was walking down an aisle recently in a chapel. Up came a little white-haired sister who burst out, “Oh, President Brown, I’ve always wanted you to speak at my funeral.”

With his eyes twinkling, he said, “Sister, if you want me to speak at your funeral, you’d better hurry.” The children of God are lighthearted. Don’t take yourself so seriously, a friend said to me, that when you walk down the street people look at you and say, “Three cheers for sin.”

Man Is Not Depraved, but Divine

But now, I bring all this, which has been rather circular, to what I pray may be a worthy and fitting end. I, brothers and sisters, have known men who were not too worthy of admiration. I have visited on occasion in prison and heard a guard say, “The more I see of men, the more I admire dogs.” I myself in honest introspection can find within me things I am not proud of—snakes and spiders, all the things Freud said, and worse. But I bear you witness tonight that the solution to that is not the one that even many religionists have come upon—the solution of saying, “All right, let’s admit it, man is absolutely no good. Man is depraved; man is indeed a worm. And if there is to be anything salvaged, it will be done purely at the initiative and solely by the causation of God. And our destiny will be to be counted with those who, likewise unworthily, were put in a place.”

My testimony to you is that you have come literally “trailing clouds of glory.” If you only knew who you are and what you did and how you earned the privileges of mortality, and not just mortality but of this time, this place, this dispensation, and the associates that have been meant to cross and intertwine with your lives; if you knew now the vision you had then of what this trial, this probation, what in my bitter moments I call this spook alley of mortality, could produce, would produce; if you knew the latent infinite power that is locked up and hidden for your own good now—you would never again yield to any of the putdowns that are a dime a dozen in our culture today. Everywhere pessimism, everywhere suspicion, everywhere the denial of the worth and dignity of man.

I have faith that if only twenty thousand caught hold of God’s living candle on that truth and went out into the world—I don’t care if the vocations are sensational, spectacular, or brilliant—just out in the world being true to the vision, we would not need to defend the cause of Jesus Christ. People would come and ask, “Where have you found such peace? Where have you found the radiance that I sense in your eyes and in your face? How come you don’t get carried away with the world?” And we could answer that the work of salvation is the glorious work of Jesus Christ. But it is also the glorious work of the uncovering and recovering of your own latent divinity. I know that idea is offensive to persons whom I would not wish to offend. I know that it goes against the grain of much that is built into our secular culture. I know that there are those who say there is no proof. But I bear witness that Jesus Christ, if there were none else, is the living proof and that, as you walk in the pattern he has ordained, you will be living proof. I bear that witness in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

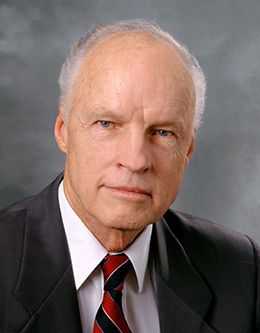

Truman G. Madsen held the Richard L. Evans Chair of Christian Understanding at Brigham Young University when this fireside address was given on 3 March 1974.