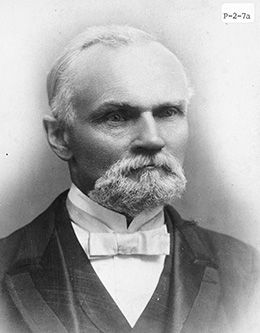

Karl G. Maeser

Karl G. Maeser was born on January 16, 1828, in Meissen, Saxony, Germany. His father was a china painter in the local porcelain shop and the Maeser family was well-known in their hometown. From a young age, Maeser had a passion for learning and education. At fourteen, he enrolled in the Kreuzchule, one of Germany’s oldest schools located in Dresden. Although graduating from the institution would have given Maeser the opportunity to catapult into the German upper class, he instead chose to study at the Fridrichstadt Schullehrerseminar, a school that trained future teachers.

After his graduation in 1848, Maeser became a schoolteacher. He tutored Protestant children in Bohemia, taught at the First District School in Dresden, and was made headmaster at the Budich Institute. While teaching at the First District School, he became acquainted with the daughter of the school’s director, Anna Mieth. The two eventually fell in love and were married on June 11, 1854. They would become the parents of eight children.

While teaching at the Budich Institute, Maeser came across an anti-Mormon book called Die Mormonen. Ever inquisitive, he decided to investigate these beliefs for himself. Maeser and his brother-in-law Edward Schoenfield called upon the Mormon missionaries and soon were being taught by missionary William Budge. Both Maeser and Schoenfield were baptized at night, due to Germany’s ban of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Anna was baptized five days later, and a small branch was opened in Dresden. Its first president was Karl G. Maeser, the new convert. This would be the first of many callings accepted by Maeser, callings that would later require him to travel the globe to build the Lord’s kingdom.

Because of their involvement with the Church, the Maeser family was forced to leave Germany in 1856. They fled to London, where Maeser was called to serve a German-speaking mission. He served in that capacity for a year until his family immigrated to the United States, landing in Philadelphia in July 1857. There he was commissioned to develop pamphlets containing basic Church doctrines and was again called to serve a mission, proselyting to the German-speaking community in Philadelphia. After three years on the East Coast, the Maeser family was uprooted again in 1860, this time to the Salt Lake Valley.

Maeser was quickly proving himself to be a strong and capable leader and the need for German-speaking Saints was great. Upon arriving in Salt Lake City, Maeser was called to preside over Church meetings in German until he was called to serve his third mission, returning to proselyte in Switzerland and Germany and eventually being appointed as the mission president. Once he completed his mission, he again presided over the German-speaking congregation in Salt Lake City.

Although he was on a new continent with a host of new Church responsibilities, Maeser’s love for teaching never diminished. In Utah, he taught at the Deseret Lyceum, the Union Academy, the University of Deseret, and the Twentieth Ward Seminary.

In 1876, Brigham Young appointed Maeser to become the founding principal of the Brigham Young Academy. The Academy was in its second experimental term and was operating poorly. However, Maeser was able to transform the Academy into a well-oiled machine as he focused on Brigham Young’s admonition that “you must not attempt to teach even the alphabet or the multiplication table without the Spirit of God.” Maeser emphasized a strong tradition of honor and implemented educational philosophies and religious ideology. The Maeser Building on campus is named in his honor.

In the BYU Speeches archives, you can find Maeser’s final address as president of the Brigham Young Academy, and his contributions to the university have inspired many devotional addresses throughout the years.

Karl G. Maeser passed away in his home on February 15, 1901, but the university still upholds Maeser’s legacy. Many students past and present are familiar with Maeser’s stalwart defense of honor: “I have been asked what I mean by word of honor. I will tell you. Place me behind prison walls—walls of stone ever so high, ever so thick, reaching ever so far into the ground—there is a possibility that in some way or another I may escape; but place me on the floor and draw a chalk line around me and have me give my word of honor never to cross it. Can I get out of the circle? No. Never! I’d die first!”