What seem to be only small deviations in direction or small detours from the straight and narrow path can result in huge differences in position down the road of life.

My dear brothers and sisters—students, teachers, and friends—I am glad to be here today. I love BYU and its people. Provo is the city of my birth. Many of the best years of my life have been spent on this campus—15 years, counting my two years at B.Y. High School on what was then the lower campus. I graduated from BYU 50 years ago this last June. It is obvious why it always thrills me to return to this campus.

Today I will speak about some lessons of life, hoping to help each of us—especially young people—with some choices we all make along the road of life.

A good news/bad news story introduces my subject. A pilot on the intercom gave his passengers this in-flight message: “I have good news and bad news. The good news is that we’re making good time. The bad news is that we’ve had an equipment failure, and we’re not sure we’re headed in the right direction.”

The direction in which we are headed is critically important, especially at the beginning of our journey. I have a friend who concluded his career as a pilot flying long routes across the Pacific for a major airline. He told me that an error of only two degrees in the course set on the 4,500-mile, direct-line flight from Chicago to Hilo, Hawaii, would cause the plane to miss that island by more than 145 miles to the south. If it were not a clear day, the pilot could not even see the island, and there would be nothing but ocean until you got to Australia. But of course you wouldn’t get to Australia, because you wouldn’t have that much fuel. Small errors in direction can cause large tragedies in destination.

All of us—and especially young people—need to be very careful about the paths we choose and the directions in which we set our lives. What seem to be only small deviations in direction or small detours from the straight and narrow path can result in huge differences in position down the road of life.

In the general priesthood meeting last month, I told about a friend of many years who told me that her husband, always a “good kid” in high school, took a few drinks he thought would help him forget some problems. Before he knew what was happening, he was addicted. Now he is not able to support his family, and he is ineffective at almost everything he tries to do. Alcohol governs his life, and he cannot seem to break free of its grip. The way to avoid being addicted is to avoid even the first step—totally refraining from all addictive substances and practices.

Potentially destructive deviations often seem so small that some find it easy to justify “just this once.” When that temptation arises—as it will—I urge you to ask yourself, “Where will it lead?” I have chosen that question as the title of my message today. I will give some illustrations that teach the value of asking that question. I will also share some personal experiences that illustrate the long-term importance of some seemingly small differences in present choices.

Here is a hypothetical. You are home with your children. A person you don’t want to talk to is calling on the phone or coming to the door. You are tempted to have the children tell them you are not home. “Where will it lead?” If you do this, you are showing your children that you will lie to gain an advantage, and you are teaching them how to do the same. You are weakening their faith that they can trust you to tell the truth. You are also casting doubt on the validity of the commandment not to lie and on the prophets who taught that commandment. You are even diminishing faith in the existence of the God whose commandment it is. Where will this lead? It will set in motion a succession of consequences that can be severely destructive of efforts to achieve eternal blessings.

In our last general conference, Bishop H. David Burton reminded us that in raising children and providing for their needs and desires, more is not always better. Parents who overindulge their children with material goods and privileges run the risk of not teaching them “important values like hard work, delayed gratification, honesty, and compassion.” Where will this lead? It will deprive children of important opportunities for learning and growth. “Children devoid of responsibilities risk never learning that . . . life has meaning beyond their own happiness,” Bishop Burton said. He then concluded that parents need to help their children build “the qualities that come from waiting, sharing, saving, working hard, and making do with what we have” (“More Holiness Give Me,” Ensign, November 2004, 98, 100).

The wrong course is also set with another kind of parental indulgence. Some parents seem to have the attitude that their children can do no wrong. They defend them against any criticism, correction, or painful experience from anyone outside the family circle. A low grade in school or a correction from a leader calls forth a storm of public or private criticism from a parent who will defend a child at all costs. Where will this lead? It will undercut a child’s respect for authority—any authority—and it will diminish the respect necessary for the student to learn from the teacher. Parents who consider where such actions will lead will support authority and back up their child’s teachers in all but the most exceptional circumstances.

There are positive examples of the same principle. I recall a story told by Elder Harold B. Lee in a devotional address here at BYU 52 years ago last month. (Incidentally, I was a student at BYU that year—1952.) His story has had a significant impact on me for several reasons. I quote Elder Lee:

I was around ten or eleven years of age. I was with my father out on a farm away from our home, trying to spend the day busying myself until my father was ready to go home. Over the fence from our place were some tumbledown sheds that would attract a curious boy, and I was adventurous. I started to climb through the fence, and I heard a voice as clearly as you are hearing mine, calling me by name and saying, “Don’t go over there!” I turned to look at my father to see if he were talking to me, but he was way up at the other end of the field. There was no person in sight. I realized then, as a child, that there were persons beyond my sight, for I had definitely heard a voice. Since then, when I hear or read stories of the Prophet Joseph Smith, I too have known what it means to hear a voice, because I’ve had the experience. [In Harold B. Lee, Stand Ye in Holy Places (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1975), 139]

Consider some of the effects of that experience. First, it taught the reality of revelation to a young boy who was to become a prophet. Second, it may have protected young Harold from some hidden danger in those old sheds. That was the way I interpreted the story for many years, and perhaps that is true. We will never know. But perhaps the warning he heard was not to protect him from danger. Perhaps it was to test his willingness to be obedient to heavenly guidance. Surely he passed the test, and where did that lead? It kept the channel of revelation open for further guidance, and it was a formative experience in the life of one of our greatest teachers. Following an impression may seem a small thing now, but where it leads can be immensely important.

Following an impression saved my life in the mountains about 10 miles from here. I had been hunting deer, just this time of year about 25 years ago. In the late afternoon I shot a large buck. I cleaned the animal and secured the carcass where it would be preserved until I returned to carry it out with helpers the next day. By this time it was dark, I was alone, and I was still high in the mountains several miles from the nearest road.

Though I had never been on this particular mountainside, I was not lost. I knew the general location, and I knew that all I had to do was keep walking down and eventually this would lead me to a familiar road. The problem was the pitch darkness of the moonless night.

I chose a gully and started to feel my way down through the brush and deadfall. It was slow going, so I was relieved when the gully flattened out to a sandy bottom beneath my feet. I picked up my pace for about 10 steps and suddenly had a strong impression to stop. I did. Reaching down, I took a rock and tossed it out into the darkness ahead of me. I heard no sound for a few seconds, and then there was a clatter on the rocks a long distance away. I knew immediately that I was standing on the lip of a sheer drop-off.

I retraced my steps and eventually got down the mountain by another gully. I phoned my worried family close to midnight, just before they called for a search party. The next day I revisited that spot in daylight and saw my tracks, which stopped just two or three feet from a drop-off of at least 50 feet. I was glad I had heard and heeded a warning. Where did that lead? It saved my life.

Now I invite you to think about some seemingly small decisions you are making in your life that would benefit from your asking “Where will it lead?”

As an example of things to avoid, consider the terrible consequences of partaking of anything that can be addictive. This includes not only tobacco and the alcohol that enslaved my friend’s husband but also the avalanche of pornographic material that assaults our senses on the Internet and in the popular entertainment, including movies and videos. Where does sampling this garbage lead? Church leaders and professionals alike affirm that it leads to the destruction of earthly and eternal family relationships—and sometimes even to prison sentences for abusive behavior. Get mixed up with this garbage and it will lead you to the landfill—the dumping ground of temporal dreams and eternal destinies.

Here is something else to avoid, a suggestion aimed especially at those of us who are married. When disagreements occur—as they will—and you are tempted to run away from your spouse for a short or longer time, ask yourself, “Where will it lead?” An angry departure is the first step toward something you don’t want to pursue. So retrace your steps and heal the wounds before they become infected and lead to serious injuries or worse.

As an example of things we encourage and where they will lead, consider the daily scripture study we have been taught to incorporate into our lives. Where does that lead? How about twice-daily personal prayers and a kneeling family prayer? There is enormous spiritual and temporal protection in each of these practices because they are essential to the companionship of the Holy Ghost, who guides us and strengthens us spiritually. I can assure you that faithful observance of these guidelines will lead us closer to the Lord, and their omission will lead us away from Him.

The same is true of holding weekly family home evenings. These are vital for the children some of you now have and most of you will have in time to come. Such basic endeavors may seem small things now, but they sow the seeds that will bring a good harvest in the future.

This reminds me of a verse composed by Douglas MacArthur when he was superintendent of West Point almost a century ago. MacArthur, a great believer in the importance of athletic competition in preparing future military officers for their professional duties, authored these words and ordered them carved on the stone portals of the Military Academy’s athletic facility:

Upon the fields of friendly strife

Are sown the seeds

That, upon other fields, on other days

Will bear the fruits of victory.

[Quoted in William Manchester, American Caesar (Boston: Little, Brown, 1978), 123]

After hearing that verse, some of you are probably thinking that MacArthur was a better general than he was a poet. Yes, but his point is sound. The same qualities of integrity, training, preparation, obedience, and reliability that produce victory in friendly athletic competition will see us on to victory and success when the stakes are larger.

To cite another example, how about the effects of failure to conform to the BYU Code of Honor and the BYU Dress and Grooming Standards after promising to observe them? It is not a small thing to break a promise, deliberately or carelessly. And where will it lead? It will drag down the appearance and standards and reputation of the Church’s university; it will encourage others to do likewise; and it will weaken the offender’s own moral fiber needed for the future, larger challenges he or she will face.

We often hear about the choice between good and evil. For example, most students will have to choose sometime between plagiarism or cheating to get a higher grade or relying on honest personal efforts to get what we deserve from our own preparation and qualifications.

Other choices are not between good and evil. The most familiar choices we face are between two goods, and here, too, it is desirable to ask where it will lead. We make many such choices in what we will do on the Sabbath, which television programs we will watch, which job offer to accept, what to read, and—on a very broad front—how to spend our time. All of these will profit from thoughtful and habitual measurement against the standard of “Where will it lead?”

Sometimes the choice is not between two different actions but between action and inaction. Should I speak up or remain silent? Should I allow my loved one to pursue a course I know to be injurious and let them learn by experience or should I intervene to save him or her from that experience? Again, it is useful to ask ourselves, “Where will it lead?”

Here I recall an event described by a man I met at a stake conference in the Midwest more than a decade ago. The setting was a beautiful campus in central Illinois. My informant, a participant in a summer workshop, saw a crowd of young students seated on the grass in a large semicircle about 20 feet from one of the large hardwood trees that are so common and so beautiful there. They were watching something at the base of the tree. He turned aside from his walk to see what it was.

There was a handsome tree squirrel with a large, bushy tail playing around the base of the tree—now on the ground, now up and down and around the trunk. But why would that beautiful but familiar sight attract a crowd of students?

Stretched out prone on the grass nearby was an Irish setter. He was the object of the students’ interest, and, though he pretended otherwise, the squirrel was the object of his. Each time the squirrel was momentarily out of sight circling the tree or looking in another direction, the setter would quickly creep forward a few inches and then resume his apparent indifferent posture. Each minute or two he crept closer to the squirrel, and the squirrel apparently did not notice. This was the scene that held the students’ interest. They were silent and immobile, attention riveted on the drama—the probable outcome of which was becoming increasingly obvious.

Finally the setter was close enough to bound at the squirrel and catch it in his mouth. A gasp of horror arose, and the crowd of students surged forward and wrested the beautiful little animal away from the hound, but it was too late. The squirrel was dead.

Anyone in that crowd of students could have warned the squirrel at any time by waving their arms or crying out, but none had done so. They just watched while the inevitable consequence got closer and closer. No one asked “Where will this lead?” and no one wished to interfere. When the predicable outcome occurred, they rushed to the defense, but it was too late. Tearful and regretful expressions were all they could offer.

That true story is a parable of sorts. It has a lesson for things we see in our own lives, in the lives of those around us, and in the events occurring in our cities, states, and nations. In all these areas we can see threats creeping up on things we love, and we cannot afford to be indifferent or quiet. We must be ever vigilant to ask “Where will it lead?” and to sound appropriate warnings or join appropriate preventive efforts while there is still time. Often we cannot prevent the outcome, but we can remove ourselves from the crowd who, by failing to try to intervene, has complicity in the outcome.

Four other subjects have occurred to me as I have pondered the application of asking “Where will it lead?” All of these concern public policy rather than private morality. However, each is a subject where our private choices and influence can contribute to the public good. Each is important to the public environment in which we live.

First, I am concerned about the current overemphasis on rights and underemphasis on responsibilities. Where will this lead in our public life? No society is so strong that it can support continued increases in citizen rights while neglecting to foster comparable increases in citizen responsibilities or obligations. Yet our legal system continues to recognize new rights even as we increasingly ignore old responsibilities. For example, so-called no-fault divorces—which give either spouse the right to dissolve a marriage at will—have obscured the vital importance of responsibilities in marriage. Similarly, I believe it is a delusion to think that we help children by defining and enforcing their rights. We do more for children by trying to reinforce the responsibilities of parents—natural and adoptive—even when those responsibilities are not legally enforceable.

The same principles apply in public life. We cannot raise our public well-being by adding to our inventory of individual rights. Civic responsibilities like honesty, self-reliance, participation in the democratic process, and devotion to the common good are essential to the governance and preservation of our country. Currently we are increasing rights and weakening responsibilities, and it is leading our nation down the road toward moral and civic bankruptcy. If we are to raise our general welfare, we must strengthen our sense of individual responsibility for the welfare of others and the good of society at large. (See Dallin H. Oaks, “Rights and Responsibilities,” Mercer Law Review, 36 [1984–85], no. 1 [fall 1984]: 427–42.)

Second is the matter of diminished readership of newspapers and books. The circulation and readership of daily newspapers in the United States is declining significantly, even while our population is increasing. Specifically, the per capita circulation of newspapers in the U.S. in the last 30 years has declined from 300 to 190 per 1,000 population. To cite another measure, in the four years ended in 2002 the percent of those ages 25 to 34 who have read a newspaper during the past week (either in hand or on the Internet) fell by almost 10 percentage points—from more than 86 percent in 1988 to less than 77 percent by 2002 (U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1989 [109th ed.], table no. 901; and Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2003 [123rd ed.], table no. 1127). The proportion of adults who read books has also declined significantly in recent years (see National Endowment for the Arts, Reading at Risk: A Survey of Literary Reading in America, Research Division Report #46, June 2004, Washington, D.C. [www.nea.gov/pub/ReadingAtRisk.pdf]; and Christina McCarroll, “New on the Endangered Species List: The Bookworm,” Christian Science Monitor, 12 July 2004, 1–3).

Why are these trends of concern? More and more people are not reading the news of the world around them or about the important issues of the day. They apparently rely on what others tell them or on the sound bites of television news, where even the most significant subjects rarely get more than 60 seconds. Where will this lead? It is leading us to a less concerned, less thoughtful, and less informed citizenry, and that results in less responsive and less responsible government.

A third concern is with what is being taught or not being taught in the schools that shapes the thinking and values of those who will be our future leaders. I refer to public schools, private schools, and ministerial schools. I fear that some of the values being taught or not being taught to the young people who will be speaking for us from the public and religious pulpits of our nation in a few years are significantly different from the values that have shaped this nation and its people. I have the same fear about what is being taught by TV programs, which command so much of our youth’s time.

After the recent election I read that one in five voters in nationwide exit polls said that moral issues were the most important consideration in casting their votes. Many of us vote on the basis of our concerns with the position of our public officials on moral issues, but what are we doing to register similar concerns with the values of some of those who are teaching our future leaders? Failure to give attention to this concern will lead us away from civic virtue, civic responsibility, and overall prosperity.

My fourth concern is with the destruction of trust in public figures and public officials. This is fresh on our minds after the recent ugliness of many election campaigns, but it is also a familiar feature of current television programming. So much of public discourse and media coverage and entertainment seems to consist of content that will destroy trust in those persons and offices that should function as moral guides for young and old in our society. Many of the messages of some recent candidates seem intended to discredit the character of another candidate rather than to promote a serious discussion of the important issues on which the electorate should register their choices. Similarly, in so-called entertainment shows we often see the authority figure portrayed as scheming, dishonest, and unworthy of trust.

Discredit authority figures—whether public officials, teachers, ministers, or others—and where will it lead? It will encourage doubts about the laws and rules and principles they administer, and it will lead to skepticism about or withdrawal from the ties that bind us together as a society, a family, or a private organization. I pray that this will not be so, and I pray for a return to public discourse that is less divisive and more supportive and respectful of authority figures and the values that have built our nation.

Where will it lead? I’ve suggested this as a valuable question against which we can measure many personal and private decisions. It is also a way of bearing testimony. Where does faith in the Lord Jesus Christ lead? Where does the gospel lead? I quote from the Doctrine and Covenants the word of the Lord to His people in this dispensation:

Seek to bring forth and establish my Zion. Keep my commandments in all things.

And, if you keep my commandments and endure to the end you shall have eternal life, which gift is the greatest of all the gifts of God. [D&C 14:6–7]

I testify of Jesus Christ who is our Savior. I testify of the truth of the gospel of Jesus Christ, which will lead us to eternal life. I testify that we are led by a prophet. This is the Lord’s church and His gospel in which we can place trust that it will lead us to eternal life. And I say this in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

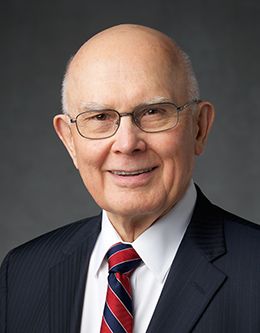

Dallin H. Oaks is a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. This devotional address was given on 9 November 2004.