Inaction carries intense inertia, and it is often difficult to do more than simply study and comment on the problems that surround us.

At nine o’clock on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday mornings, in a plain room on the bottom floor of the Jesse Knight Humanities Building, I attended my first English class at Brigham Young University—a class about writing for the social sciences in which the first 10 minutes of discussion was only rarely related to the syllabus. The professor was passionate and inspiring, and he got a thrill out of bantering with us about art, politics, and the idiosyncrasies of life on campus. He would show us ragged torn-out pages from his favorite art books, inspire us by reading aloud fantastic examples of voice-filled prose, and joke, for example, about how you could practically brush your teeth with the frosting from the BYU Creamery’s mint brownies. I always viewed this portion of his class as somewhat of a respite. Not only did I perceive the world of technical writing as inherently stale, I also simply appreciated his honesty and verve.

It is from this professor, in the opening moments of one day in this class, that I was most forcefully reminded of the responsibility that accompanies knowledge and the effort required to make a college experience worthwhile in the fullest sense. It happened about six weeks into the course. I remember being a southpaw sitting in a desk designed for a right-handed student, rubbing my hands together after walking in from an early autumn chill and wondering what our class would cover in the next hour. Soon the professor, too, walked in, sat down, and slowly started as usual into random but meaningful conversations with his students. I don’t remember what the initial topic was, but somehow we got into a discussion about what it takes to turn belief into action, and he made one pithy statement that often occupies my mind. This is what he said: “Apathy is your passion.” As you might imagine, it came across as a pointed accusation. My classmates and I were from a variety of majors—some sociology, some international relations, some political science—but, in the professor’s mind, we were all apparently passionately apathetic toward the suffering of others and toward social and political problems. Personally, I was at first turned off by the remark, thinking it impossible that students majoring in the social sciences, physics, biology, or even the arts could be entirely apathetic about the well-being of others and the state of the world. “After all,” I thought, “aren’t pain and dysfunction phenomena that all of our studies at least obliquely address, attempt to better understand, and even reduce?” It seemed counterintuitive that students so consumed in efforts to learn about the world could be indifferent toward what is probably one of its most ubiquitous conditions: human suffering.

My professor didn’t extrapolate, and the class discussion soon shifted to technical writing, but I kept thinking about that one statement—“apathy is your passion.” It seemed that he was making an accusation of apathy based on what he had observed of human behavior in general. In retrospect, I don’t think he meant to specifically question the character of his students. Knowing myself, however, his comment fell on at least one set of deserving ears. It’s probably not too difficult, moreover, to find people—both on campus and off—who would rank highly in terms of intellectual passion for the study of foreign policy, medicine, anthropology, and other topics and at the same time rank poorly in terms of out-of-class efforts to produce change. I’m certain now that this is what my professor meant. He was talking about an apathy that is physical in its demonstration, not intellectual.

On the occasion I have described, there were probably no more that 15 students present, but I imagine that this professor has made a similar statement to many of his classes since. Indeed, I imagine that he would make a similar statement to most college students if he had the chance. I also imagine that he even accuses himself of passionate apathy at times. This is because although maybe only an enticement for the best of us, the reality is that a habit of inaction can be a passion for everyone—whether we study politics or physics, whether we are students or salaried corporate executives. Inaction carries intense inertia, and it is often difficult to do more than simply study and comment on the problems that surround us.

I briefly mention this story about my English professor because I think his insight is important for new graduates. We all have a great new opportunity to make use of the knowledge and skills we have acquired, to make sure that apathy is not our passion. I also mention the story because I have admired my professor as a person who effectively combines spirited involvement in the community with study. Others, however, also deserve compliments for their varying efforts to combine intellectual pursuits with real action. Apathy is a difficult passion to discard, but I have been deeply impressed on numerous occasions by the ability of both faculty members and my peers to make precisely this move. A friend of mine, for example, recently set up a nongovernmental organization to facilitate microlending to the suffering citizens of Mozambique. He did this entirely on his own, and only a couple of months after graduating. A friend who graduates today will soon be joining AmeriCorps in an effort to provide support for underprivileged inner-city youth. And several other peers have impressed me simply with their ability to creatively influence public perception regarding issues of social concern.

I feel lucky to have had the chance to interact with these and many other amazing, unassuming activists during the past four years. Observing their passionate interest—proven through action—in the state of the community, nation, and world has been among the most valuable experiences I have had at BYU. It has motivated me and probably others to overcome the natural human tendency for inaction. It has further validated the important lesson I learned on an early autumn morning from an inspiring English professor. It has reminded me that true passion is a vital component of achievement, success, and greatness. As we reflect today on our undergraduate experience, I hope we can view what’s next as a tremendous opportunity to be passionate actors. We have all entered to learn, and we are now on the verge of exit. I hope that as we go forth to serve, we can do so in a way that shuns apathy and exudes intense, passionate energy.

Thank you.

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

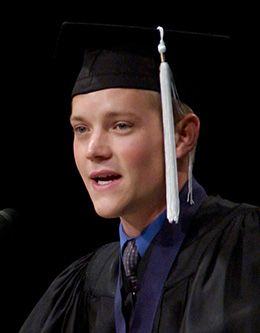

Ryan Matthew Scoville spoke as the representative of his graduating class at BYU commencement on 14 August 2003.