I was invited during the week by the Universe to name a subject about which I might speak, and I was hard put to it; so, finally, I recalled reading somewhere a statement by a French philosopher, a one-sentence statement. I have never read the works of this philosopher—I do not even know his name—but I liked what he said as the subject about which I wish to speak this morning: “From the living flames of our campfires of the past rather than the dead ashes.” That is the subject.

Ashes have no life. Flames are constantly moving, changing, and challenging. Anybody who sits at a campfire can watch but never tire of the variety of the flames that arise from the burning wood. And after the fire has died down and he has gone through the action of killing it with water or whatever, running his hands through the dead ashes, he finds that the ashes are not very much once they are dead. I debated for some time as to whether or not I should come to you with a doctrinal subject, but you get a lot of that—nearly all of the Brethren who come here to speak to you talk about the doctrines or variations of the doctrines—and I thought perhaps I could tell you young folks what is really in my own heart, as if I were speaking to my own. And I can take advantage because I am old enough now to be able to do it and not have people think that I am eccentric. One debates whether to hide his earphone and his contact lenses and his teeth, which are extractable (he cannot do anything about his hair so he does nothing about that), and stands before you in the latter part of the life trying to tell what he has learned. So here is what I have learned from the living flame.

In righteousness, one may be guided by the spirit of the Holy Ghost in his personal affairs if he seeks such guidance and if these affairs are honorable and honest. I want to call your attention to the fact that there is a place in the 89th section of the Doctrine and Covenants which says something like this: “All [those] who . . . keep and do these sayings” (the Lord has been speaking of tobacco and liquor and other noxious substances, as well as wheat and corn and rye and barley—and there might be one added: “Retire to thy bed early” [D&C 88:124], which is not a part of this particular section—but says this:) “walking in obedience to the commandments, shall . . . run and not be weary” (D&C 89:18, 20). I have talked to several athletes of my acquaintance who wonder why they are running weary; but they do not seem to realize that they are not walking in obedience to the commandments. It is told us in the 93rd section of the Doctrine and Covenants that if we will do all the things we ought to do, we may see the face of our Savior (see verse 1). On the same basis you may be guided by the Spirit of the Lord, the Holy Ghost, in your personal affairs if you are honorable and honest and keep the commandments.

I have discovered that one is guided sometimes even if he does not ask for it. Nearly all of the occasions in my life when I have had great events foretold my by the Spirit, I have never invited them myself or asked about them. They have just come. I can see why that is: because every person who joins the Church and is a member of it in good standing has a right to receive the constant companionship of the Holy Ghost. He is given the right at baptism and he keeps that right as long as he is righteous. I have come to the conclusion that this Spirit and whatever influence he uses to reach us is more anxious to help us than we are anxious to be helped. I found that out quite early. So you may be sure that if you are doing your normal things in righteousness, there will come to you intuitions, feelings, revelations which will guide you if you can understand that Spirit and how you’re having it. It takes a little work to understand when it is there, but you can learn it.

I found that it is true in that very important thing called marriage. In one case (I have been married twice, as you might know) it came without asking. I did not ask for it, but the guidance came anyhow. In the other case it came after asking, but just as clearly as in the previous case. So I know that if you need guidance, whether or not you seek it, if you are righteous and have not made previous decisions, you will receive guidance. Of course, if you have already made up your mind, you will not; but if you have not made up your mind and are wondering, you will.

I have found that it is true in Church assignments. I knew in 1945, two months before I was called, that I would be a member of the First Council of the Seventy. I can remember my feeling at the time. I was standing near the grave of my mission president, who was a member of that council, paying my respects to his family, and it came to me that I would succeed him. I gave my head a shake and said to myself, “Don’t be a fool. No such thing can happen.” I fought it, but it didn’t do me any good to fight it because the more I fought it the more strongly the impression came. On the day it occurred I could have told you the exact language which would be used in the call, and it proved to be so.

I received a call to preside over the New England Mission and the method by which I found out had nothing to do with that mission—it was so far removed from it that I could hardly believe it—but a month before I received the call, right out of the clear sky, when I was thinking of something else entirely, I had a very distinct revelation that that would happen.

I name these two incidents not because I am exceptional; I think it is also true of men who become bishops. A woman told me a few days ago that she had a premonition—not a premonition but a warning—that she was going to be made teacher of a certain Sunday School class, and she was. It does not matter what the calling is; you can receive knowledge ahead of time that you are to receive it if you have the Spirit of the Lord in your hearts.

I found that it is true in civic affairs, the most noteworthy of which was an occasion when I was to serve on a grand jury. I had every excuse in the world not to serve. If I served, my Boy Scout camp would not open. It could not, because in the days of the Second World War we could not hire a man to help get it ready, for there were no men to hire. So I had to get it ready personally. There were seven or eight hundred boys expecting to come to that camp. When I saw my name in the newspaper among forty others who might serve on the jury, I said to myself, “Well, I won’t serve”; but as I said it to myself I knew perfectly well that I would and that no matter what I said to that judge I would not be able to escape it, and that proved true.

I found many times in my life when these things have come to me, with and without asking. But I found out also that if I was not righteous or was not doing righteous things at the moment, it never happened. Whether one asks or not, one must live so the Spirit can dwell in him. That is the key to the whole thing—living so the Spirit can dwell within you. And, of course, you know what that means: that means, in plain, common English, behave yourselves.

As I look back upon my life I see that I have been protected or helped in danger and crisis. I look back and at the time I did not see it, but now I look and see that I could not have made it without. For example, as a boy eight or nine years old I was standing with some other boys—my brother and two others—in a semicircle, and the boy at the other end of the crescent had a Sears and Roebuck twenty-two caliber single-shot pistol, two dollars and fifty cents with tax, and he was showing us how Buffalo Bill used to shoot. Buffalo Bill was supposed to pull his pistol and fire in this manner [illustrates]; but the spring on this pistol was broken, and my friend had an elastic band around the hammer and around the trigger guard. The way he did it was to pull it back and let it go with his thumb. He was firing this pistol down into City Creek Canyon when all of a sudden I felt my arm go numb. I looked down and saw a red spot forming on my arm right there [pointing to left bicep]. Then my hand went numb, and I realized that I had been shot. That is what I said as I ran for home; but afterward I thought, had that pistol turned one sixteenth of an inch farther I would have had it. Now I do not say that the Lord kept that pistol from turning, but something did.

I climbed Long’s Peak one time with a group of men. Long’s Peak is 14,256 feet high, and as one gets above the thirteen-thousand-foot level, he finds, unless he is used to it, that his legs go numb about every fifth step. One can go four or five steps and then his legs go numb, and he has to wait for them to come alive before he can go farther. It took us about an hour and a half or two hours to go the last thousand feet.

Up on top I noticed that there was a ridge apparently running down in a direction which, if I could get on it, would save me the hours of going around the way we had come. Against the advice of my companions, I decided that I would take that shortcut. So I dropped down off the peak into a series of ledges which were waist high, just like a giant staircase, and before very long I was a thousand feet down. Then I ran into ice. During the evening before there had been an ice-storm up there. It was clear ice; one could not see it on the rocks, and the first thing I knew I slipped. I caught myself and then began to worry; for I could see when I got there that I could not make that ridge. There were glacial cirques on both sides thousands of feet deep, and I was caught. I cannot tell you how panicked I was. I was terribly frightened. I realized that the only way I could escape was to work my way, somehow, back to the top. Every so often I could hear a whistle blow up on top; that meant that one of the men was still up there. I will not describe the things I went through to start back upward to get out of the particular danger I was in, but finally I got to where I could move. I went up that thousand feet in twenty minutes without even losing my breath. You will say, perhaps, that it was adrenaline, but it was not; and when I got to the top there was Golden Kilburn, a man who was with us, waiting. He said, “I couldn’t leave. I knew you were in trouble, so I decided I would not go down this mountain till I found out where you were.” And I found out there the value of friendship, too, and of the loyalty and devotion of those who care for you.

One time, on the way to Mexico to attend the funeral of my brother-in-law, we were driving along from Cortez, Colorado, south toward Gallup, New Mexico. It was January, and the thermometer was by the actual count ten below zero. We had a Chevrolet with no heater in it. We were so bundled up in blankets that we could hardly move. There was a ground blizzard, and the snow was drifting across the road so that one could hardly see it. I was going along about fifty miles an hour, the lights penetrating not more than seventy-five or eighty feet in front, when all of a sudden there loomed up in front of me on my side of the highway, a horse, with another horse directly behind him, starting across the road.

There was no time to stop. To this day I do not know what happened. All I know is that that horse jerked his head back as I went by on the left side of the road, then I was back into the right-hand side again. My life was spared, and so was that of my wife. I did not do it. There was no time to do it. There was no time to think; but some guiding hand had forced me to turn that car into the left-hand lane and back again, and some guiding hand had kept it from skidding as it went around. By all the laws it should have skidded off into the borrow pit or I should have struck the horse. At ten below zero, we would never have survived.

Sister Young had a stroke two days after we got home from a trip we took to Mexico. It incapacitated her for the rest of her life, and I had the honor and the great pleasure of nursing her for the five or six more years she lived. Had she had the stroke two or three days before in Quetzalcoalcos, Mexico, in the southwest corner of the Gulf of Mexico, we never should have gotten her out alive, but mercifully it waited till she got home.

When I was young, I came home from a mission and needed a job. I got married and was working for a hundred and twenty-five dollars a month when I heard there was a job in Scouting in Ogden. An old friend, Howard McDonald, past president of your University here, met me on the street and wanted to know if I wanted that job.

“What is it?” I asked.

He said, “You get paid for being a Boy Scout leader. Lots of fun. You direct the Scout work in a community.”

The only thing I had ever done in Scouting was to help my little brother in a fire-by-friction situation. I showed him how to make fire by friction in our kitchen, and all I succeeded in doing was boring a hole through our kitchen linoleum. So I said that I was not interested; but all the way home that night I thought, “Well, why not? Maybe I could do it. I don’t know what it’s about.” So I applied to the president of the local council in such a manner that he was not impressed—anything but impressed. I was frightened, I was stuttering, I was hesitating, I did not know what to say, I could not give him any reason for wanting the job, I did not know what the job was, but I said, “I want it.”

He looked at me casually, and finally he said, “Well, we are going to receive written applications, so if you want to write an application we’ll read it.”

So I wrote the application, and to my surprise I was invited to come to a meeting where I could be interviewed. There were eight candidates, all of whom had had years of experience in volunteer Scouting. I had had none. At that time, however, I suddenly became very calm, very sure of myself. I did not have the least fear. When my turn came to speak—each of the others had taken at least thirty minutes each, so it took nearly all day to hear them, and I was the last one—the president reminded me that they were all tired. So I said, “I don’t know a thing about this job, but I know that I can learn to do it rapidly,” and then I sat down. To my surprise, I was one of two picked out of that crowd to appear before the board; and with that much of a statement before the executive board, against a man who had had fifteen years of experience, they chose me.

Looking back upon it, I can see the steps by which I was inspired to say the things I said and not say the things I should not have said to get that job. It proved to be good. I had it for twenty-three years before I became a member of the First Council of the Seventy. I am certain as I stand here that the Lord directed me to that job through Howard McDonald and others, and that I was given it, not because of any qualification—not at all—but because somehow I was supposed to have it. I can bear you my witness that you yourselves (only in your case get prepared; this is not 1923) will find the opportunity that will take you to your life’s work so that you can have the joy.

Well, the campfire flames mount. I have learned some guideposts in that period of time, and I would like to pass them on to you. The first one is: “One must always tell the truth.” Dr. Jeremiah Jenks, a great psychologist of his day, let me have that one time. I was at a big meeting and he was speaking about honor and dignity and truth-telling. Incidentally, you might be interested in knowing that he was the man who was instrumental in seeing to it that the Boy Scout Law contained, “A scout is reverent,” and also that the oath had, “I will do my duty to God.” Otherwise we would have been kind of pagan in our Boy Scout business. He was a great Christian. But he was speaking, and a man in the audience raised his hand and interrupted him and said, “Dr. Jenks, should one always tell the truth?” thinking about the little white lies one tells about how good the dinner was when it wasn’t, or “I’ve to go somewhere; I’ve got to quit talking on the phone,” or all those other things we do.

Dr. Jenks, aged then about seventy-five, looked out at that man and smiled and said, “Young man, if the truth is told in a courteous manner, the truth may always be told.”

I give you a quick illustration that I have told before many times. Many years ago I was driving home late one night from Provo to take care of my sick wife. I was very nervous because I had prepared things for her to last until six o’clock at night, and I was starting home from Provo at eleven o’clock at night, so she had already been without help for five hours. I was fit to be tied. I passed through Salt Lake City (I had not been arrested so far between there and Provo), and started up the highway toward Ogden, got as far as Farmington junction, and turned off on to the hill road, newly paved at that time though not straightened out. With that I stepped on that accelerator and got the car going seventy miles an hour. I passed the road where Hill Field takes off going seventy-two or -three; it was downhill a bit, and going down the hill I think I increased to seventy-eight or eighty. And then I noticed through my rear-view mirror the flashing light of the patrol car. I pulled to a stop and got out and walked back fifteen or twenty feet, extending my hands so he could see I was not armed, and he came up and stopped a few feet away and got out. “I guess you’re arresting me for speeding,” I said.

“Yes, you were doing better than sixty miles an hour when you passed the Hill Field road.”

“I was doing better than seventy miles an hour when I passed the Hill Field road,” I corrected him. “But give me a ticket; I’ve got to go. My wife’s sick, I’m in a hurry, and I’ll pay the fine gladly, but let me get out of here. I’ve got to go home quickly, so just give me the ticket.”

He said, “Don’t get your shirt off. Stand still a minute. I’m not going to give you a ticket.” He had not asked for my name. He just stood there.

I said, “Well, thanks for that.”

He continued, “I’m going to give you a warning ticket. That means you don’t have to go to court unless you do it again. On one condition.”

“What’s the condition?” I asked.

“That you drive within the speed limit the rest of the way home, so you will get to your wife.”

I said, “I’ll do it.”

So he gave me the ticket and when he handed it to me it had my name on it. He smiled, stuck out his hand, and said, “My name’s Bybee. I used to be one of your Scouts at Camp Kiesel.”

All the way home I said to myself, with each turn of the wheels on my car, “What if I’d lied to him? He knew I was doing seventy. Policemen do. He knew I was going too fast, and he knew I was his Scout executive years before, too.” I did not know that he knew any of this, but if I had not told him the exact truth or tried to hedge at all he would have lost respect. He would have given me a ticket, and I would have had no influence on that man ever again.

And so it is with you. You are always doing seventy, no matter where you go or what you are doing, and you had better admit it. Then you will get a reputation for honesty and honor and it is so great that it will save your life many times. If you get in crises—your word against someone else’s word—and if you have a reputation for being truthful, it will save you. That has been my experience.

You must be absolutely honest, of course; that goes along with truth-telling. You cannot afford to do one thing that is not absolutely honest. I commend to you the one thing that many people are not honest in and that is truth-telling in examinations. I do not think that any teacher is ever fooled by a boy who cheats. The boy fools himself. But if he tells the truth, his fifty-percent grade is more honored by the teacher than the ninety percent he might have gotten if he had lied; and what he doesn’t know he doesn’t know anyhow. That is part of truth-telling.

There are many other phases, of course. You must set your ideals so high . . . well, you have to set your ideals as high as the Lord said to set them: “Be ye . . . perfect, even as your Father . . . in heaven is perfect (Matthew 5:48). And then, if you do that and live up to some of them, you will be able to live up to many of them. Some of them you will compromise in spite of yourselves, but you will not compromise enough of them to jeopardize yourselves if you have them high enough. But if you only have them half-high and start compromising you do not have much, and you are left desolate and barren. So set your ideals as high as you possibly can set them in conduct and handling yourselves and doing what you ought to be doing. If you do that you will find things happening to you that will surprise you.

I can say, now that I am getting to the stage where I am old enough to testify to it, that the greatest thing next to heaven itself is a clear conscience, as far as your personal life is concerned. When one is my age, he looks back upon the things he has done wrong and says to himself over and over again—or I say to myself over again—“Why did I do that? Why did I do that?” and there never is an answer. And I suppose that is what hell is like. You never get the answer—and that is futility. But if your conscience is clear, how happy your old age is! It is a time of such rejoicing that you cannot possibly imagine how wonderful it is. You know what things you have to do and what you get if you do them without my naming them over one by one—these become the pearls you count. A man never needs to apologize to any woman for the way in which he treats her or has treated her in the past. He knows his mind is clean, and therefore his speech is clean.

Vulgar talk is a great temptation. Little half-swear words, the damns and the hells, come easy, I guess. They have done so to me. I punched cattle once and discovered the cattle did not know any of my language, so I tried the language they knew. I wish I had tried my cleaner language on the cattle a little longer. They might have learned something, and I would certainly have saved myself trouble. It is a temptation. Once one of my present associates got irritated and, in saying something over the phone about getting us to move faster, he used a little word with it that made us want to move faster; but to my surprise one of my colleagues, listening on a collective phone, said, “I don’t like that. I don’t think he ought to use that word. We don’t need that here. We’ll move without it.” And that was just a very simple word. I learned the lesson that there are men in this world and women in this world who want to have clean minds, and want to have clean thoughts, and are insulted if you violate their ideal. You can find them; you don’t have to look very far for them. Just be that way and they will gravitate to you.

Live in such a way that you can pray. Most people pray, but I am talking about being able to pray with the assurance that you can be heard. We say our prayers, but are you praying and am I praying with the assurance way down deep that what we are saying is heard where it ought to be heard? That only comes with clean living, with what we call repentance. We must truly repent of our sins, and start to make ourselves better, and try to live cleanly, and then we are heard. The Lord can hear us and he will hear us and he does hear us, and then what I said in the beginning takes place: the Holy Ghost works on you, whether you want him to or not.

When you do these things, you will have another great compensation come to you. Your life will be such that when you listen to leaders speak—leaders such as the President of the Church or the apostles or the bishop of your ward or your class teachers—you can discern whether that person speaks by the Spirit or not, and that is vital in your life and in mine. We Latter-day Saints can have no other standard than this, that we live in such a way that we will be able to discern when people are speaking by the Spirit. If you have that you have a pearl of great price, and you will understand and know the way by which you may become perfect. Brigham Young is reported to have said once, “The important thing is not whether I am speaking by the Spirit of the Holy Ghost in conference, but whether or not the congregation can detect the spirit by which I’m speaking.” He was more worried that the audience would not have enough spirituality to hear what he was saying by the Spirit than he was that he speak by the Spirit, and I am worried about the same thing right this minute. I hope that I am speaking by the Spirit; and if I am not I hope that you in this congregation will all have enough discernment to know whether I am or am not, or what I am and am not. Anybody who speaks from the pulpit in this University ought to stand that test, and you ought to be testers and be able to do it.

Brigham Young had a dream once, and I think it is the epitome of what I have been trying to tell you:

Joseph stepped toward me and looking very earnestly, yet pleasantly said, “Tell the people to be humble and faithful and to be sure to keep the Spirit of the Lord and it will lead them right. Be careful not to turn away the still small voice. It will teach them what to do and where to go. It will yield the fruits of the kingdom.” Then he repeated, “Tell the brethren to keep their hearts open to convictions so that when the Holy Ghost comes to them their hearts will be ready to receive it. They can tell the Spirit of the Lord from all spirits. [Now, here’s how you can do it, too.] It will whisper peace and joy to their souls. It will take malice, hatred, strife, and all the evil from their hearts, and their whole desire will be to do good, bring forth righteousness, and build up the kingdom of God. [That’s how you can know whether or not you have the Spirit.] Tell the brethren if they will follow the Spirit of the Lord, they will go right. Be sure to tell the people to keep the Spirit of the Lord and if they will they will find themselves just as they were organized by our Father in Heaven before they came into the world. Our Father in Heaven organized the human family, but they are all disorganized and in great confusion now. [And then, finally,] Tell the people to be sure to keep the Spirit of the Lord and follow it, and it will lead them just right.” [Manuscript History of the Church]

Just imagine; the President of the Church has a dream or a vision in which the Prophet Joseph comes to him, and he spends all that time telling him one thing over and over again. That is what it is, brethren and sisters, young folks.

One last thing: I shall tell you how you can measure your spiritual discernment. Nephi became ecstatic one time, and he prayed to the Lord and praised the Lord and sang paeans, psalms, and kept becoming more spiritual and more spiritual, and finally he made a great statement, a great prayer: he said something about “wilt thou do this for me,” “wilt thou keep my soul,” “wilt thou feed me,” and went on like that, “wilt thou do this”; then finally said, “Wilt thou make me that I may shake at the appearance of sin?” (2 Nephi 4:31). He was so spiritual that the least deviation from having the Spirit, which is sin, he could discern, and that is what he wanted most of all.

And so with you and me. Let us learn to shake at the very appearance of sin, and we can measure our spirituality by how much we do that. If we do not shake, we are not very spiritual, and if we shake, we are. And the more we shake at the appearance of sin, the more we are spiritual.

After all, the final thing is that the Father and the Son do live and guide us, and the Church established by Joseph Smith is the Church of Christ, the only Church of Christ. That is the great testimony, to know that President Kimball is the real prophet of God our Heavenly Father and his Son, and to follow after and keep the commandments of the Lord which our prophet teaches us and to know when he speaks by the Spirit. I know that he does and I know these things are true, and so do most of you, I suspect. May we all unite together and go forward and earn our place in the kingdom of our God by keeping the Spirit and understanding, I pray in the name of Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

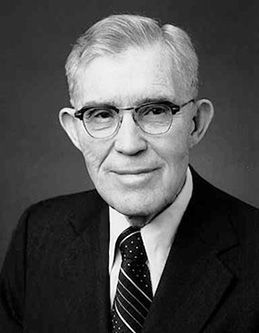

S. Dilworth Young was a member of the First Quorum of the Seventy of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 17 May 1977.