This is the eighth time I have addressed the student body of Brigham Young University at the beginning of the Fall Semester. It is always a humbling experience for me. You have a right to expect a significant and useful message, and that poses a great challenge for the President of the University. In trying to meet that challenge I usually reemphasize some things I have said before. I do this because each year I face a new group; only about half of you were here last year, and less than that the year before. Part of my responsibility is, therefore, to stress the same ideals, to reaffirm the same truths, and to give the same advice. Hopefully, my message will be enriched by new experience and new insights that will offer an element of interest to the faculty and others who have heard it before. But my most important objective is to encourage you to do your part to keep BYU and its students on the same steady course we have pursued for over a century, reaffirming the unchanging ideals and truths and the advice that has proven its worth for generations.

Each of us knows the law of the harvest: “Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap” (Galatians 6:7), and “He which soweth sparingly shall reap also sparingly; and he which soweth bountifully shall reap also bountifully” (2 Corinthians 9:6). There are a few areas of human activity where the law of the harvest applies more directly than in the pursuit of the knowledge. Those of you who sow sparingly will reap sparingly in the acquisition of knowledge and intellectual accomplishment. The same is true of spirituality. Oh, there will be examples where a person who has sown sparingly may reap a higher grade or be called to a more significant and apparently more desirable church position than one who has sown diligently. But there are things more important than grades or positions; those are only means to an end. In terms of real progress toward our final goals, which are knowledge and eternal life, the law of the harvest is inexorable.

There is another aspect of the law of the harvest, also of eternal significance. It is expressed in the familiar saying, “Where much is given, much is expected.” When the Lord of the harvest has lavished great attention on a particular portion of his vineyard, he expects it to bear fruit, at least in proportion to the attention he has lavished. The prophet Isaiah illustrated this expectation when he described the Lord of the vineyard who “fenced it, and gathered out the stones thereof, and planted it with the choicest vine,” and “looked that it should bring forth grapes. . . .” When it brought forth wild grapes instead, the Lord of the vineyard cried out in anguish, “What could have been done more to my vineyard, that I have not done in it?” Why, he asked, when he looked for it to bring forth good fruit, did it fail? Then he called his servants to take away the hedge, break down the wall, and lay waste to the vineyard. “The vineyard of the Lord of hosts is the house of Israel,” Isaiah explains, and when the Lord, considering all the advantages he had bestowed upon this chosen people, “looked for judgment, but [beheld] oppression; [looked] for righteousness, but [beheld] a cry,” he decreed that the vineyard should be made desolate (Isaiah 5:1–7). Where much is given, much is expected.

The Savior reemphasized the same thought in the parable of the barren fig tree:

A certain man had a fig tree planted in his vineyard; and he came and sought fruit thereon, and found none.

Then he said unto the dresser of his vineyard, Behold, these three years I come seeking fruit on this fig tree, and find none: cut it down; why cumbereth it the ground? [Luke 13:6–7]

Where much is given, much is expected.

How does all of this apply to students of BYU? What have you been given? You have recently paid your tuition, $420 for one semester if you are an LDS undergraduate, and more than that for others. It is a large sum, and you and your parents probably sacrificed to pay it. But notwithstanding that sacrifice, do you really think you are paying your own way at Brigham Young University?

For every dollar you pay in tuition, the leadership of the Church appropriates more than two dollars additional, which is provided by the tithepayers of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. And beyond that, generous donors contribute other important dollars to increase the facilities of this campus, to support its work, and to provide scholarship and loan funds so that some of your number with very special qualifications do not even have to pay all of the $420 tuition.

Every dollar given to support this institution is given as a freewill offering, often at great sacrifice. I suppose I do not need to tell all of you, though some of you may need to be reminded, that there are sacrifices entailed in paying ten percent of your salary or wages before taxes. That is the practice of the full tithepayers of this Church. For the most part, tithing is not paid out of abundance. Many who pay tithing around the world would look on your housing, food, and clothing—to say nothing of your automobiles—as luxuries beyond what they and their children could ever expect in this life. Many have had no opportunities for higher education in their lives and little more for their children. But they pay tithing, for the Lord has commanded it; and a large proportion of the money they pay is appropriated by the Lord’s servants to pay for your education.

Is it any wonder that every tithepayer in the Church looks on Brigham Young University as his or her university, supported by his or her own sacrifices? Is it any wonder that the leadership and membership of our Church have a very special interest in how BYU students and faculty and other workers accomplish their work and how the University and its students look to the world?

There is another group whose existence reminds you of something you have been given. They are students who wanted to study at BYU whom we have not been able to admit, and the parents of these applicants. Every year there are more applicants on the outside looking in. Some are not yet qualified for study at BYU, but many of them are. They are forced to wait or go elsewhere because we do not have room to admit them. The completion of your studies will make space for them, and many wait. In a very real sense they are also contributing to the opportunities you now enjoy.

If any student at Brigham Young University, man or woman, is ever inclined to think that what he does in his studies or with his life while at BYU is of no concern to anyone but himself—that “it’s my life and I am not hurting anyone but myself,” as we sometimes hear—I hope that student will remember the tithepayers and other donors who are paying for his education, and the eager and worthy students who are praying for the opportunity to take his place. Where much is given, much is expected.

And now I move to a second theme, closely related to the first. As I do so I invite you to participate in an informal quiz—surely an appropriate exercise on the first day of school. Unlike the quizzes on the last day of school, this one will not be graded; but like every other quiz, it should be interesting and challenging and should serve an educational purpose.

I invite you to look through my eyes at six events I have observed on campus or things I have read or heard on campus. Each has something in common. Your challenge is to visualize the circumstances and identify the common element. Then we will relate it back to our first theme, “Where much is given, much is expected.”

1. A week ago this morning I stepped out of the Smoot Building at 8:30 in the morning to walk to the Wilkinson Center. It was a glorious day. The rays of the sun bathed the campus in early-morning splendor. The dew glistened on the neatly groomed lawns. The flowers along the west side of the Harris Fine Arts Center provided a rich color contrast. The flag stood out proudly against a blue sky. And someone had put detergent in the fountain. The suds foamed, and some members of our maintenance staff—called away from other needed tasks—were preparing a cleanup operation.

2. We have an extraordinarily beautiful campus at BYU. It is beautiful because we spend a great deal of time and money on landscaping and cleaning—caring for lawns, shrubs, flowers, and floors. We do this to provide an atmosphere of beauty for our students. We think that learning, which we believe is promoted by the Spirit of the Lord, goes forward most effectively in an atmosphere of order and beauty. We are also concerned with the appearance of the campus, since thousands of visitors come here to see the University of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. These visitors are tithepayers, persons investigating the Church, and prominent people who wish to see Mormonism in action. In order to keep the campus beautiful, we ask that persons dispose of litter in waste containers and not walk across the grass. Sit on it, stand on it, use it for lounging, but do not put feet on it to cut corners and make a path. We have concrete walkways for that. Ever year I make that request at this opening assembly. And every year, when we leave the Marriott Center, scores of students walk across the grass on their way back to class. Most of our students—thousands in number—watch them from the sidewalks.

3. A student is in academic trouble. Parents who have sent him to BYU with great sacrifice are heartbroken because he is not succeeding. Academic probation has been imposed, and academic suspension is the next step unless there is a speedy change. He is remorseful. His teachers regret the circumstances. Everyone wishes it were otherwise. “What went wrong?” I ask.

“Well,” he says, “I have a hard time studying in the dorm. It’s noisy. The fellows there are always horsing around, and I just have to be involved with them. I can’t study in the dorm. I guess I could go to the library, but . . . well, I just like to study in my dorm room, but I can’t because of my roommate and what’s going on in the hall outside.”

4. Every day my office gets hundreds of letters. After they have been examined to remove the routine and the matters that can be handled by others, I still have from fifteen to fifty pieces of mail for my personal attention. Here is one that came a few months ago from Donald K. Nelson, the director of the Harold B. Lee Library. He suggested two library problems I might mention in this talk; they fit in well with my theme. I quote:

Two problems exist; one is total theft where a patron will take either an entire book or entire magazine from the library without checking it out through the proper procedures. The second problem, more difficult to curtail, involves mutilation. Patrons will cut a picture or an entire article out of a magazine or an art print from a book, or even sections from microfilm. Once the book or magazine has been mutilated, we try to replace the item or secure Xerox copies from another library and have them reinserted into the magazine or book. When these efforts fail, the University permanently loses the use of these materials.

5. Here is another example of a letter from my mail. Try to read it through my eyes. It comes again and again, primarily from BYU students, but also from parents, from visitors to the campus, from tithepayers. Aside from letters praising the University, which comprise the largest single category in my mail, this kind of letter is probably the most frequent. It says something like this: “In our class there is a fellow who wears his hair so long that it is clearly in violation of BYU Dress and Grooming Standards. It isn’t that he is just a little too late in getting a haircut. He isn’t anywhere near the standard.” Or the other version tells of the young woman who comes to class in blue jeans. I am not speaking here of nicely tailored denim pantsuits; I am describing jeans that are men’s trousers or women’s trousers suitable for hiking or slopping the pigs, perhaps modish for some high school somewhere, but not acceptable at Brigham Young University. “Why can’t they keep the dress and grooming standards?” the letters ask. “They have promised! Please do something, President Oaks!” Another letter of this type reads like this:

I brought some friends of ours who were investigating the Church to see Brigham Young University, where my husband and I graduated ten years ago. We brought them to the campus because we are so proud of it. We had told them about the standards of the University. But when we walked through the Wilkinson Center and across the campus we saw someone walking in bare feet, and some girls in blue jeans, and some fellows with long hair, and some couples necking on the lawn, and we were just humiliated. Doesn’t BYU have its standards any more?

6. Last example: Every day I read the Universe. It is an excellent campus paper, and I hope you read it too. You need to know what is there. Read it now for a moment through my eyes.

It does not happen often, but sometimes I see something in the Universe that I know to be untrue or at least seriously misleading. It may be in a headline, in an article, or in an editorial; but, more likely, it is in a letter to the editor. One of the stated justifications for letters to the editor is that they give campus people a place to let off steam. Here we read every variety of communication, from brilliant constructive criticism to the most inane and juvenile prattlings. My usual reaction on reading these letters is to marvel at the diversity of opinion we have on the campus. This diversity is valuable—even essential—in a university community, since we learn and grow as we confront a variety of ideas and points of view. But some letters are seriously misleading. One may undertake to describe a University policy, but do so incorrectly. Another may state as a fact something that is not a fact. I am not referring to personal perceptions, ideas, or experiences; I speak of published material that describes policy or makes other representations of fact on matters where the truth is readily available to the writer but was not obtained or used. The erroneous impression created by such a letter to the editor is either careless or malicious—usually just careless, probably nothing more than the exaggeration we are all inclined to employ at times. Most readers laugh and shrug it off, and so do I. But not always.

Sometimes these careless misrepresentations concern something newsworthy, an important matter in which the public is interested. The results are predictable. We have reporters for each of the major wire services on campus, and one of their primary sources is news copy from the Universe. Whatever appears there, if it has general public interest, is almost certain to appear on the following day in a wire service story to satisfy the curiosity of a coast-to-coast readership. For example, last year one flamboyant letter to the editor in theUniverse was immediately seized and used as the sole basis for a wire service story about a “dissenting movement on campus,” representing the campus as being divided on an important issue where I judge that the campus—perhaps including even the writer of the letter—was remarkably united. It is sad but true that Brigham Young University is often represented to a national audience by a third-hand process which begins with an individual student’s representation of facts in the Universe, and which is then filtered through the always selective and sometimes sensational intake of a wire service stringer and editor. I sigh.

And so I have spoken of suds in the fountain, paths on the lawn, noise in the dorm, mutilation in the library, jeans on the women, long hair on the men, and distortions in the paper. What do they have in common? And what do they have to do with my theme?

We find the answer in a letter the apostle Paul wrote to the saints in Corinth over nineteen hundred years ago. Professor C. Terry Warner made the point in a devotional talk over eight years ago on this campus. With his help I now enlarge on the insight he offered.

Paul wrote to answer some members’ questions about whether it was wicked to eat the meat of an animal that had been sacrificed to an idol. I have been in Corinth and seen the sites of those ancient pagan temples. With the aid of the scriptures I can visualize the circumstance. As part of the service of worship of a pagan god, an animal is killed and sacrificed to the idol. Afterwards there is a feast, and the flesh that had been part of the sacrifice is served to those who come to eat. The meal is relatively open. Some who are there are devout idol worshippers. Others are Christians, some accompanying their pagan friends—just there to observe—and others perhaps wavering in their Christian faith, wondering whether they should resume the idol worship from which they had been converted. One Christian partakes of the meat, and another criticizes him. A controversy arises in the church in Corinth, and Paul is asked if it is sin to partake of meat that has been sacrificed to an idol.

Paul’s response is a mixture of reason, faith, and Christian charity, a suitable model for us in every respect. First he reasons with the congregation. “We know,” he tells them, “that an idol is nothing”—a lump of brass or a mound of clay (1 Corinthians 8:4). Consequently, the fact that an animal was slaughtered in connection with a ceremony involving an idol does not affect the meat in any way. Nor is the eating of meat of any special significance to God. Consequently, Paul writes, “neither, if we eat, are we the better; neither, if we eat not, are we the worse” (1 Corinthians 8:8). Knowledge of gospel principles liberates us. We are not bound to honor superstition or to revere inanimate objects. That was the reasonable answer, and if Paul had been solely concerned with reason or knowledge in their narrowest sense, that would have been the end of the matter.

But there is more to the gospel than just knowing the truth and by that means being liberated from the chains of false beliefs. We are also responsible to conduct ourselves so that we edify and help others and do them no harm. Paul had alerted his readers to that fact when he began his letter with these words:

Now as touching things offered unto idols, we know that we all have knowledge. Knowledge puffeth up, but charity edifieth.

And if any man think that he knoweth any thing, he knoweth nothing yet as he ought to know. [1 Corinthians 8:1–2]

So “knowledge puffeth up, but charity edifieth.” And when we are puffed up and think we understand something by our superior knowledge—so called—we should not act before we pause and ponder the possibility of an additional, spiritual insight and gospel obligation. Was there one in this case?

Paul reminded the saints at Corinth that not every brother who took meat in the house of the idol knew that the idol was nothing, that the ritual of sacrifice was empty and the meat unaffected. Some wavering Christians may have thought that they would show respect to the idol by partaking, thus making their act of eating a form of idolatry. To others, former idolators, the eating of meat in an idol’s temple may have been looked upon as a temptation to return to their old ways. Thus, there were those who, though mistaken, felt in their hearts that eating this meat was wrong, because if they were to eat it they would “eat it as a thing offered unto an idol; and their conscience being weak [would be] defiled” (1 Corinthians 8:7).

Paul was reminding the Corinthian saints that the knowledge they had about the harmlessness of the meat should not be their only consideration in deciding whether to eat it. They should also consider the impact they would have on others. Listen to the way he explains it:

For if any man see thee which hast knowledge sit at meat in the idol’s temple, shall not the conscience of him which is weak be emboldened to eat those things which are offered to idols;

And through thy knowledge shall the weak brother perish, for whom Christ died? [1 Corinthians 8:10–11]

Take heed lest by any means this liberty of yours became a stumblingblock to them that are weak. [1 Corinthians 8:9]

The gospel requires us to act with concern for others, whom we love. And what if we do not? Paul concluded with this sobering reminder: “But when ye sin so against the brethren, and wound their weak conscience, ye sin against Christ.” His resolve, then, was to be the model for the Corinthians, and for all of us: “Wherefore, if meat make my brother to offend, I will eat no flesh while the world standeth, lest I make my brother to offend” (1 Corinthians 8:12–13).

The gospel obviously provides a loftier vision of our responsibilities than is suggested by the comment that “it’s my life and I don’t care what others think.” “Knowledge puffeth up, but charity edifieth.” Because of all that we have been given, we at Brigham Young University need to be especially concerned about how things look to others—about our effect on others—lest our behavior become a stumbling block to our weak brother. When we sin against our weak brother—for whom Christ also died—and weaken his conscience, we sin against Christ. Therefore, if any of our actions offend our brother we should avoid them. Can you see the bearing of that principle on suds and distraction, on jeans and long hair, on vandalism in the library and distortions in the media? Surely you can relate that to the principle, “Where much is given, much is expected”? Paul’s charge to young Timothy will serve as an appropriate summary and conclusion of this point: “Be thou an example of the believers in words, in conversation [i.e., in conduct], in charity, in spirit, in faith, in purity” (1 Timothy 4:12).

Having given some negative examples, I will close with a positive one, of BYU students to whom much was given, from whom much was expected, and who were a worthy “example of the believers.” This group met the challenge and represented BYU and our Church and nation in a way that can make us all proud. I refer to the Young Ambassadors who performed this summer in Poland and the Soviet Union. Three other great BYU groups were performing abroad this summer, the A Cappella Choir, the Lamanite Generation, and the American Folk Dancers. All made us proud. I describe the Young Ambassadors because theirs was the special challenge of being the first organized group ever to represent the Church or the University in the Soviet Union. My wife, June, and I were blessed to travel with them.

The group consisted of twenty-eight BYU students, including five dancers, ten singers, nine orchestra members, and four technicians for sound and lights. The tour director and spiritual leader was Professor Gray Browning of our Russian faculty. The creative director was Randy Boothe of the Entertainment Division. Our objective in sending the group was to provide a living example of Americanism and Mormonism to the people of the Soviet Union.

The Soviet agency responsible for the tour had agreed to four performances. When they saw the quality of the BYU group, they kept adding performances until the Young Ambassadors finally had nine full shows in Rostov Veliky, north of Moscow, in Kiev (the capital of the Ukraine), and in Moscow itself.

The Russian people were extremely curious about Americans and Mormons, and very warm and loving in their response to our students’ performances. The applause was usually tentative at first, but progressively warmer until the last three or four numbers, when the audience clapped in unison and kept the group for several encores and several of those choice occasions when the performers came down into the audience to distribute BYU buttons, postcards, and autographs, to grasp the outstretched hands, and to exchange words of friendship. By then, the look in the eyes of the people in the audience, which I saw clearly because I always seated myself among them, could only be described as shining. During some of the numbers I saw tears in their eyes and a positive look of rapture. You could see their growing understanding of the message of friendliness and love communicated by our BYU students.

Before leaving on this trip, most of the twenty-eight students had taken a semester-long course in Russian language and culture from Dr. Gary Browning, so each had enough phrases to carry on a simple conversation with the people they met. After the performances many of the people would remain in the hall, embracing our students and telling them how much they loved the program and how good it had made them feel. After one show in Kiev, a handsome young man of about thirty-five, accompanied by his six-year-old son, introduced himself to us as the Communist Party secretary in charge of culture in that district of the city. He told us through Dr. Browning how impressed he was with the program and especially commented “on how good it made him feel—what a beautiful feeling it communicated.” That comment told us we were accomplishing our objective in the Soviet Union.

Our students were responsible, as the Psalmist said, to “sing the Lord’s song in a strange land” (Psalms 137:4). But that could only be accomplished—that beautiful feeling could only be communicated—by those who had spent many months of grueling work to bring their program to a professional level, and who were then willing, unselfishly and cheerfully, to give many, many days in the exhausting routine of performance after performance. More than that, they had to work together harmoniously and live in tune with the Spirit so that they could be instruments in the hands of our Heavenly Father in communicating his Spirit. In all this they succeeded, and the results were beautiful to behold.

My wife and I also witnessed what I have called “The Miracle of Montana.” Early this summer, during a mini-tour to Montana, the Young Ambassadors appeared on the Montana Television Network on the program Today in Montana. While they were working with the producer of this program, Norma Ashby, a tourist who had just returned from the Soviet Union came into the studio. She brought a gift to Norma Ashby from a Soviet television executive whom Norma had hosted in Montana during the executive’s tour of the United States several months earlier. When the Soviet executive, Svetlana Starodomskaya, chanced to meet this American tourist in Moscow some time later and learned that the American would be traveling through Montana, Svetlana asked her to take a gift to her friend in Montana. The gift arrived during the forty-five minutes our students were in her studio. This was the beginning of the “Miracle of Montana.”

When Norma Ashby received the gift, she promptly asked our group to take a return gift to Svetlana. So it was that when the Young Ambassadors arrived in Moscow their leaders sought out Svetlana Starodomskaya, who turned out to be a senior executive of Soviet Central TV. This great state network, housed in an immense building in Moscow, programs for thirteen time zones in the Soviet Union. After seeing one of the group’s performances in Moscow, Svetlana invited the Young Ambassadors to come to the studio and tape their show for Soviet Central TV.

June and I were present for the videotaping, and we felt that we were present at history in the making. In that giant Soviet studio, with every modern electronic advantage in cameras, scenery, lighting, and sound, the Young Ambassadors videotaped an hour-and-a-half program. Through their diligence and faithfulness, and through the very evident help of our Heavenly Father, a schedule that originally contemplated a scant four performances had miraculously escalated to a nation-wide television program, which has now been telecast to a viewing audience of approximately 150 million people in the Soviet Union. That is the audience to which the Young Ambassadors were blessed to extend the message of brotherhood and friendliness in the American songs, “You Gotta Have Friends,” and “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother,” and in the popular Russian folk song, “Let There Always Be Sunshine.” The quality of their show was so high that Svetlana told us as we left the studio, “Whenever you return to Moscow, we want you back on Soviet Central TV.” BYU has more standing with the media in Moscow today than it has in New York City.

I call all of this “The Miracle of Montana.” Imagine, taking a small group of students for four performances in Russia, and winding up with a performance before a television audience of 150 million! Can that be a coincidence? It is a testimony to me that when we are ready the Lord will use us for his purposes.

I could tell you much more about this trip, including the church services we held, the testimonies borne, the rapt attention of the Russian women who slipped into the meeting to feel its spirit, our experiences performing on the street in Kiev, passing out literature in an unprecedented informal tracting exercise, and much more. But I must close by sharing only one more experience, which relates directly to the examples with which I began, the question of how we appear to others.

After the Young Ambassadors had taped the television show, Svetlana told how much she admired our students, especially the young women. “Your students are not sexual like most young people nowadays,” she said. “They are modest in all of their gestures, even when they are expressing very deep feelings.” Then she asked: “What does it mean to be a Mormon; how are Mormons different?” At that point it was easy to share what we wanted to share, and we made a friend.

I was proud as I felt the impact of our students’ appearance and performance and as I felt what they had been able to communicate, spirit to spirit. They had been scrupulous in observing BYU standards, and they had been willing to make the effort and the sacrifices necessary to qualify themselves to present the kind of entertainment we wished to have representing the University and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I hope every student in this University will remember the impact that group had on the Soviet audiences and a Soviet television executive. “It made me feel good,” he said. “Modest,” she said. And then she asked, “What does it mean to be a Mormon?”

And so we come to a new year. Many of you are new at BYU. This is the first day of classes. You can write on a clean slate in the records of this school year, for good or for ill. The same is true of your personal lives, in the important matters covered in the BYU Code of Honor, which you have promised to observe.

As you confront the inevitable temptations in your personal lives and the pressures toward mediocrity in your studies, I hope you will remember the responsibilities I have reviewed with you today. Remember also that where much is given much is expected. That our Heavenly Father may help each of us to measure up to this challenge is my prayer in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

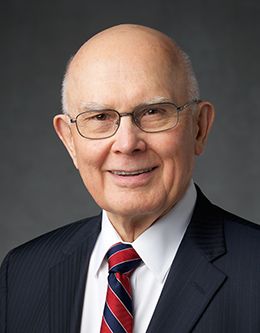

Dallin H. Oaks was president of Brigham Young University when this devotional address was given on 5 September 1978.