The Sword of the Lord and of Gideon

Assistant to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles

September 26, 1972

Assistant to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles

September 26, 1972

Comparisons are not appropriate, and I make none, but that choir is certainly unexcelled.

I was kind of hoping I could say the same with reference to football, as I mention to you what I heard from Jerry Kramer, the professional football player. He was talking about the man glued to his television set, whose wife said, being able to bear it no more, “Henry, you love football more than you love me.”

And he said, “Yes, but I love you better than I love basketball.”

I should make an explanation to a couple of puzzled young men that I met on my way in here. Things are not always as they seem. For instance, I read from the Fayetteville, Arkansas, Courier the other day the interesting little news item that Thomas Brown, while fishing at Lee’s Point some time ago, lost his gold wedding ring. Last week, while he was fishing again at Lee’s Point and cleaning a fish he caught there, his knife struck something solid. It was his thumb.

The two young men who were on their way in here saw me getting into my car. I said, “You’re too late, men; your watch must have stopped. It’s over.” They watched me as I drove out and then came to a closer parking spot, because I have, unfortunately to depart these premises immediately after this assembly is through, and we’ll have to forbear shaking hands, which I like to do more than speak to you. I’m going, I should say—almost nothing else would be important enough—to keep an appointment with that one son President Oaks mentioned. He and I for a long time have had a date at noon today, and so I must go and be there.

I had a recent experience with Richard that was important. He was ordained a deacon by his father a few weeks ago. His mother and I were privileged to go to the Sunday morning priesthood session, the general session, where he was presented to the brethren. He walked steadily to the front, this fine-looking, fine young man, and stood by the bishop as his name was presented for receiving the Aaronic Priesthood and ordination to the office of deacon. We had a chance to vote. Later, as he reported this incident to his sisters, who were not at the meeting, he said, “I was kind of frightened walking up that aisle all alone and standing up there by the bishop, until I looked down and saw Dad’s hand higher than all the rest.” And he’s right. It was as high as I could put it. And in all earnestness and sincerity, that’s how high I’d put it for you, because I think you and what you can do are of great and grave importance. Not what you will do, necessarily—what you can do.

I had the great experience this morning of driving down Provo Canyon after a few hours yesterday of hard physical labor, and of enjoyment of the beauty of that place. I thought of many things, including one story I must share with you, which suffused my soul. I saw a picture of a young man on a weekly newspaper magazine a while ago. He had long hair, a typical mod outfit. He was standing by a motorbike, and I suppose some might have indulged the thought that here’s one of them, or another one. I read the article, it’s a story of a young man, twenty, who has leukemia and has had it for years. Every Monday morning he drives twenty miles or more on that motorbike to a great medical center, where for two and a half or three or more hours they subject him to the medication and the treatment which have prolonged his life beyond expectation. It’s such a traumatic, terrible shock to his emotional and physical self that, as he rides those twenty miles back on his motorbike, he understands that for several days—two, maybe three—he’s going to be so ill that he can hardly bear it. During those days he repeatedly assures himself that he will never make that trip again. It isn’t worth it. And then he has a day or two, or maybe three, to sit across the table from his mom, and to work with his dad a little bit in his construction business, and to ride his motorbike and look at the sky and the trees and the beauty of this world. He said a very vital thing: he said, “It seems to me that I’m kind of sitting on a plateau overlooking the rest of humankind, watching them assail each other in hostility over a missed appointment, or an improper word, or an unkind thought, while I sit there thanking God for one more day to be alive.”

I pray the Lord to bless you and me with sense enough to be appreciative of that wonderful blessing.

At midnight I had a well-prepared—whether appropriate or not—talk to present to you, and then the idea came that I worked on just a few minutes this morning and which appeals to me as the one I must express to you. A few weeks ago in Salt Lake City a twenty-six-year-old man was buried. He had fallen off a mountain peak while climbing. He was an expert climber, but there was an accident and he was killed. He was going to enter medical school the next week; he’s a graduate of a great university in the West. He and his sister are the only members of the Church in their wonderful family, and he’s special.

What I have to say today is not in eulogy or memoriam of Bob Allen but is inspired by a remark passed on to me by the mother of a lovely young lady who, in a family home evening when the members of the family were invited by a wise father to tell what they had learned this summer, referred to Bob Allen’s funeral as one of the most marvelous experiences of her whole life. Sad as it was to lose this kind of a young man, excellent in every way, she said, it was a day of rejoicing and uplift—a sublime day. She said—and she was so sincere—“I wonder what they would say about me.”

They who spoke at the funeral were the former bishop of this young man, now a president of a university, and Bob’s roommate over many years—his dear friend for more than eight years in school, on missions, where they corresponded, and back in school and through graduation. The bishop is a marvelous man of great spiritual depth. His sermon couldn’t be excelled. The young man was unsure and heartsick. He said he’d been laughing and crying all week long intermittently, as he read the letters from Bob, and as he thought over what this young man had meant to him. He gave an estimate of Bob Allen’s effects on him and others. Today I’d like to talk about the four gifts he said Bob gave him, and invite you seriously to consider the value and virtue of a life when it can give such gifts.

Bob, he said, gave him the great blessing of seeing one who really served. For Bob believed in service. He believed in sharing, and that was the word that seemed to get the emphasis, the sharing that had characterized this young man as he reached out to so many others in so many ways. He mentioned the little car Bob had owned. He said, “We spoke of it as ‘our car,’ because that’s how he made it to me. I tried not to take advantage of that.” Because he was so gracious, he shared—he shared his time, his talent, his concern.

I sat thinking my own thoughts on the stand that day, and I’ve thought them since, and I’ve had a great blessing this morning thinking about what Bob did and what each of us can do. God loves every one of his children—of that we are absolutely assured, and we know it in our hearts—but God needs an instrument of his love. He needs those who can take his love and make it meaningful and personal in the lives of others.

I think with delight of a great story I learned as a boy and came across again last week, almost afresh, after years of intermittently referring to it. It’s the story of Gideon—Gideon, who faced armies described as like grasshoppers, with camels as numerous as the stars in the heavens; Gideon, who had a big army, but some of them were excused, then others were sent home, and then, with three hundred, he undertook the job of facing the Midianites. Do you remember how he divided his three hundred into three groups? He taught them what to do because he was creative and God was helping him. Each had a lamp in a pitcher, and a trumpet, and at that critical moment, as the watch had just changed, Gideon gave the signal. They broke the pitchers, the lights showed, the trumpets sounded, and the great war cry went out: “The sword of the Lord, and of Gideon!” (Judges 7:18). The enemy was routed in confusion, slaughtering each other.

That’s a great, marvelous theme: the sword of the Lord and of Gideon.

I was in Nha Trang once, in a meeting where the sword of the Lord and Gideon was talked about by some of our troops who were doing marvelous work, sharing and teaching and giving beautiful representation to the principles they believe in. And then I went up to a place called Da Nang and met with another group of troops that same day. A man stood in marine major uniform—he’d been a bishop; he’s been one since. It isn’t he as it is not Bob Allen that I particularly praise today, though I have great love and respect in my heart for them and many others. What I praise is a principle, a principle application to every one of us. He stood, this man, and told humbly how he felt about being where he was, in the miserable business in which he was engaged, bore his witness, sat down, and was followed by other young men, one of whom said something the midst of a simple, beautiful testimony that keeps ringing in my ear. He was nineteen years old, a stalwart, wonderful young man. He looked down at the major in the marine uniform who’d spoken before and he said, “Thank God for Major Elliott. Since I met him, I’ve been trying to keep my life clean and sweet. And I can look you in the eye and tell you that my life will stand inspection.”

The sword of the Lord and of Gideon. To share our energies, our gifts, our skills, our faith, our love, dependent as we do it upon Almighty God, whose arm we are, whose tongue we are, when we, with authority, represent him; whose hand we are as we perform the work of his ministry. To share and serve.

The second point was discipline. The speaker at the funeral told about Bob’s discipline—physically and in terms of cultural, educational, and Church activity and attainment. They used to go over to the football stadium, he said, at 4:00 everyday, because Bob loved being fit. They’d run up and down the stairs until they were so exhausted they couldn’t do it anymore, and then Bob would say, “Let’s try a few windsprints.” He had a little motto: When things get tough, fight back.

Well, I’ve been thinking about discipline. I read the words of Mahatma Gandhi again the other day. (We stood at his tomb in India not many years ago and thought our thankful thoughts.) “Even for life itself,” he wrote, “we may not do certain things. There is only one course open to me: to die, but never to break my pledge. How can I control others, if I cannot control myself?”

There are many forms of discipline, many expressions and applications. Some of us are waiting until we graduate to begin to care about other people, until we get the degree to begin to live. Some of us even wait until morning, or until it’s warmer, to pray. Discipline suggests a course and a determined effort to keep to that course.

Sometimes discipline is great courage. Years ago I cut from the newspaper and saved a statement from Charles Edison, governor of New Jersey, about his father, who on December 9, 1914, was all but wiped out by a roaring inferno that destroyed the building where his life’s labor were stored, including the old red brick laboratory in which his current and future inventive efforts were concentrated. Damage exceeded two million dollars, insurance coverage not a tithe of it. Charles, then a young man, stood watching this inflammable material explode, the freight cars burn, the lifework of his dad go up in smoke, and then turned to see his father, sixty-seven years old, standing by the laboratory doorway, disheveled by the strenuous exertion of helping to fight the fire, his white hair tossed by the December wind. Thomas Edison turned to his son. “‘Where’s Mom?’ he wanted to know. I couldn’t tell him. ‘Go find her. Tell her to get her friends down here right away. They’ll never see anything like this again as long as they live.’” Charles Edison said, “On that grim December night I was 24. My father was 67.” Before the ashes were cold, Thomas Edison turned to his discouraged associates with these words: “You can always make capital out of disaster. Now we are rid of our past mistakes. Let’s go to work.”

The discipline that comes close to all of us may be expressed by something appearing in the newspaper the other day about Gary Player, this great golfer from overseas. He lost a tournament by failing to sign the scorecard, which is automatic disqualification. When he violated the rule, he was asked if someone in the scoring tent couldn’t have reminded him to sign the card. Listen to what Gary Player said—it cost him that day the winner’s prize, which was much more than the runner-up. “My friend,” Player replied, “there are responsibilities in life. You cannot shove your responsibilities on the shoulders of someone else. It was my responsibility to sign the card. I failed to meet it; so I must suffer the consequences.” There is so much to say about discipline—that measure of self-control, that quality of character—that knowing a way moves us to follow that way, to keep the rules.

The third point of that wonderful young man in the sermon was to comment on Bob’s excellence. He mentioned the piano which Bob played so well, and that he went over every morning to the institute to practice the piano because he was going into medical school and felt he wouldn’t have enough time to keep really sharp, and he wanted to be good. One of his friends played some magnificent Brahms that day on the piano, and the young man who spoke said, “I wouldn’t have known Brahms from anybody else till I lived with Bob. But while we spent some time listening to rock, which he did with good nature, he also taught me to love Brahms and the other greats, and he would explain to me the different ways in which Brahms could be played. He helped me to want to be what he was.”

Well, excellence can mean many things. There can be excellence of performance, creatively. I heard the story once—and love to repeat it—of the two thousand Pennsylvania high school seniors gathered at the University of Pittsburgh to be feted for their excellence. There had been many speakers, many programs, banquets, and they were jaded a bit with it all. That last day, though, their speaker was a man who, when he was introduced as one of those chiefly responsible for the development of the Salk polio vaccine, stood and snapped the braces which reached past his waist, took the two hand crutches, and laboriously made his way to the podium. Seeing their faces, sensing what had happened, and, with great wisdom and inspiration, I think, he said, “We didn’t perfect the vaccine in time to save some of us. Thank God we developed it in time to save you. What will you do for the next generation?” And then he made his way laboriously back to his chair.

Well, excellence can be in behavior, manners, courtesy; and that’s available to anyone. Prime Minister Nehru, in his last public utterance, said: “People have become more brutal in thought, speech, and action. The process of coarsening is going on apace all over the world. We are becoming coarsened and vulgarized because of many things.” And then he made a plea to stop the process of vulgarization. There can be excellence of character, of choice, of quality of our life-style. There can be excellence of manners and of courtesy. And then I thought, as perhaps some of you have, of the two statements made in these two books about a more excellent way, one by Paul the apostle, as he finished the story comparing the Church to the body of a man and then emphasized for us all that each member is of vital importance and that the head can’t say to the foot or to the eye to the hand, “I have no need of thee.” There can be excellence in home teaching, excellence in teaching in a classroom. Do you remember how he used the words? Let me read to you from Ether, the twelfth chapter, how Moroni referred to the more excellent way. It’s in this chapter that he reaches into the past for illustrations of great faith.

Wherefore by faith was the law of Moses given. But in the gift of his Son hath God prepared a more excellent way; and it is by faith that it hath been fulfilled. [Ether 12:11]

The gift of his Son made available the more excellent way, and in that all of us cannot only be accommodated but can achieve.

So much more of importance to say. Let me make the last point made by the young man, emphasized and testified to, and it may be one you’d expect to hear. He said, “Bob Allen gave me the gift of love. He taught me what it means to love. He loved his family; he loved them in a way I had not understood. We had a landlady,” this boy said, “who was more than ninety years old and who, in the natural course of events, didn’t get much attention from the energetic young students rushing back and forth. But one night, not long before his death,” he said, “Bob spent three hours, three hours he had much use for, sitting down in the living room, listening to her tell the story of her own son, who’d been named Bob, and of her life.”

Bob became a volunteer worker with the foreign students on his campus. He loved people, and many times, said his young friend, he would say, “I think I’d better go see Kioshi or Kevin, or someone else. I think maybe they need to talk.” He’d come back much later and tell of a pleasant visit.

Do you recall a scene from Ecuador in the newspaper which related to the Bible several years ago? A group of Christian Missionary Alliance workers in Ecuador were killed by the Indian tribe they were helping to learn Christianity. The people never had a chance to learn, and their alphabet was obscure. These young missionaries were learning the alphabet and trying to teach them when they were all killed. They were marched away to die, and they went singing a wonderful old Protestant hymn, its text taken from the book of 2 Chronicles: “We rest on thee, and in thy name we go” (2 Chronicles 14:11). Their wives and families are back in Ecuador now, teaching that tribe.

A week ago Sunday, in the stake conference I was attending, a young man was called to the pulpit without notice—he had had a few minutes only that morning. I wish there were a way, somehow, to pass on to you what he said and how he said it. I can try. He said he’d been away to school and came home to find a very dear friend, a beautiful young lady with whom he’d had a long acquaintance and a very respectful one, now way out from where she had been before. She’d started on the drug habit and had become so dissolute and tragically destroyed a figure that he couldn’t believe it. He said he went home—and this is a young man with two college degrees, on his way to a third—he went home that night and got on his knees and began to talk to the Lord. He said it was as if he had had, for the first time in his whole life, his own private revelation on prayer. “I cried out to the Lord for her,” he said. “I didn’t just say words. I wept. My whole heart was concerned for her. I cried to God for help. I wanted his strength in helping me to help her. And while I prayed,” he said, “I came to a consciousness I have never before enjoyed. My concern for her was intense and all-consuming and very sincere. And I knew, as I prayed, that the concern of Almighty God for me was just that kind, but of godly quality.” He talked about his own life, which had not always been exemplary, and he finished, as I’d like to today, with reference to a revelation given to Joseph Smith at a time of terrible trial, unbelievable trial for him.

You remember he was young and vigorous. He had had magnificent experiences. He had, in vision, enjoyed the ministrations of angels; in his own lifetime he had seen and conversed with Almighty God and his holy Son. He had a great people, a great mission, and he found himself incarcerated in a filthy dungeon, not fit for animals. In section 121, in those first marvelous words, he cried out to the Lord in understandable anguish, “O God, where art thou?” He was answered. In section 122 is part of that answer. I’ll say nothing after I read these words. Listen to them carefully, please.

If thou art called to pass through tribulation; if thou art in perils among false brethren; if thou art in perils among robbers; if thou art in perils by land of by sea;

If thou art accused with all manners of false accusations; if thine enemies fall upon thee; if they tear thee from the society of thy father and mother and brethren and sisters; and if with a drawn sword thine enemies tear thee from the bosom of thy wife, and of thine offspring, and thine elder son, although but six years of age, shall cling to thy garments, and shall say, My father, my father, why can’t you stay with us? O, my father, what are the men going to do with you? and if then he shall be thrust from thee by the sword, and thou be dragged to prison, and thine enemies prowl around thee like wolves for the blood of the lamb;

And if thou shouldst be cast into the pit, or into the hands of murderers, and the sentence of death passed upon thee; if thou be cast into the deep; if the billowing surge conspire against thee; if fierce winds become thine enemy; if the heavens gather blackness, and all the elements combine to hedge up the way; and above all, if the very jaws of hell shall gape open the mouth wide after thee, know thou, my son, that all these things shall give thee experience, and shall be for they good.

The Son of Man hath descended below them all. Art thou greater than he? [D&C 122:5–8]

In the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

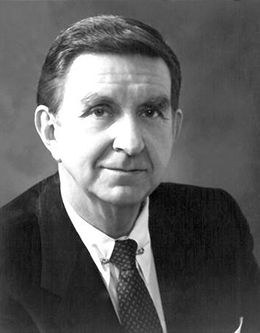

Marion D. Hanks was an Assistant to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this address was given at Brigham Young University on 26 September 1972.