Reconciliation with God is at the core of the gospel. Reconciliation is, after all, the object of the Atonement wrought by the Son of God.

Reconciliation is not an uncommon word. We hear it used in reference to reconciling one’s bank account, to bringing one’s own records into harmony with the bank’s records. We hear it used in reference to a husband and wife who, after going their separate ways, have come back together, as one, becoming reconciled. The basic meaning of reconciliation is resolving differences and returning to peace and harmony. Until we make good on our resolves, covenants, pledges, and promises, we are out of balance, not reconciled, and we suffer the consequences. When we substitute self-interest values for true, eternal values, we only deceive ourselves.

Stories help bring home the meaning of reconciliation. There once lived a young king whose wife died, leaving him an only daughter. The king’s name was Midas. His daughter was sweet and loving, and Midas loved her very much. In his treasure chamber Midas kept tons of gold: gold dust, gold bars, gold coins, gold platters, gold goblets, gold statues, even gold cooking pots. Every day he would go down into his treasure chamber, locking the door behind him, and there he would play with his riches, gloating in the power and influence he thought these would bring to him.

For hours he would sit on the floor and count his money. He would toss it into the air and laugh as it rained gold on his head. He would wallow in the gold dust, and he would dance on it. “Except for my daughter, my little Merigold, it is gold that is my treasure. Merigold’s beauty, like that of a flower, will fade. Only gold is forever beautiful. How I love to touch it. If I can only get enough gold, I’ll be happy forever.”

One day as he was gloating over his treasure, he suddenly became aware there was someone standing beside him. It was an immortal visitor come down from heaven.

“Well, Midas, you have a lot of gold, I see.”

“Oh, it’s not so much. Really, it’s only a little.”

“You are not satisfied then?”

“No. I want more, much more.”

“How much more would it take to satisfy you?”

“Oh, I wish I could create gold by the touch of my hand.”

“Create gold by the touch of your hand? Are you sure that with such power you would then be satisfied?”

“Oh, yes. Nothing else in the world would bring me such happiness.”

“Are you sure you would never regret it if everything you touched with your hand turned to gold?”

“Never.”

“The temptation would not be more than you could handle?”

“Oh, believe me, I could handle it.”

“Then it shall be as you wish. From tomorrow at sunrise, whatever your hand touches, it will turn immediately into gold.”

The next morning Midas began to experiment with his marvelous new power. Just as the immortal visitor had promised, everything he touched turned to gold.

He took a walk in his flower garden, touching the flowers one by one to test his magic gift. Sure enough, no sooner did he touch a flower than it turned into gold.

“Isn’t that marvelous!” he laughed as he danced about, touching one flower after another. He would have turned all the flowers into gold, but seeing that it was breakfast time he went inside.

Just then his servant brought in his breakfast. The king reached out to take a piece of fruit. Putting it into his mouth without looking, he found that it, too, had turned to gold. He almost broke his teeth trying to bite into it. He took a cup of tea, but before he could bring it to his lips, the cup and the tea turned to gold. The thought struck him: “If I can’t eat or drink, I’ll soon starve to death.” But looking at the fruit and the cup of tea, he only shook his head and marveled at their shining beauty.

At that moment little Merigold came running in, laughing joyously. Looking at her, the king thought: “She is as radiant as the sun.” He reached out his arms to her, but as he touched her hand she instantly turned into a lifeless statue of gold. In a panic, Midas fell to his knees and cried out, “No! No! Oh, what have I done? God, forgive me! In my lust for gold I have destroyed my own daughter.”

Just then the immortal visitor appeared again before him.

“Midas, you are weeping. What has happened?”

“Oh, immortal visitor, I am of all men most miserable.”

“Is it that I did not keep the promise I made you?”

“No, you granted me my wish. Whatever I touch turns to gold.”

“You told me that that power would bring you happiness, but now you tell me you are of all men most miserable. How can this be?”

“Oh, I didn’t realize how evil my selfish wish was. My lust for gold has robbed me forever of happiness.”

“But, Midas, is not gold the most beautiful thing in all the world?”

“I detest the very sight of it.”

“Tell me, is not gold the most valuable thing in all the world?”

“Immortal visitor, tell me wherein gold has its value.”

“Well, surely it is more valuable than a cup of tea, is it not?”

“No. A cup of tea is of more worth than all the gold I possess.”

“Surely gold is more valuable than a piece of fruit, do you not agree?”

“No. A piece of fruit is of more worth than all the gold I possess.”

“Is gold not more valuable than a daughter’s love?”

“Oh, immortal stranger, you don’t understand. I have come to see that the common things of life: our children, our friends, even the ordinary things we see and touch every day, these are our real treasures.”

Seeing that the king’s sorrow was genuine, the immortal visitor took pity on him and said, “Would you have me remove the power I gave you, and let you restore your daughter’s life?”

“Oh, noble stranger, do this and I will give you all my gold.”

“Then, Midas, go and wash your hands in the river. And bring back a pail of water. With the water from the river, sprinkle whatever you have touched and it will return to its normal state. Then use your gold to help your people.”

King Midas took a pail and ran to the river, washed his hands, and ran back to his palace with the pail of water. He splashed water on the gold statue of his daughter, and she was at once restored to life. Then he fell to his knees, took his daughter in his arms, and sobbed: “Oh, Merigold, forgive me! God, forgive me!”

After that, King Midas lived a happy life, for he found true value in his family, his friends, and even the ordinary things of life that all of us see and touch every day.

Among the scriptures that have profoundly moved me since I first read it in my youth is one given by the Lord to Joseph Smith in these words: ”Lift up the hands which hang down, and strengthen the feeble knees” (D&C 81:5).

Truly, Joseph Smith’s life was characterized by extraordinary charity—lifting up hands that hung down and strengthening feeble knees. William W. Phelps, a member of the First Presidency and Joseph’s intimate friend and confidant, left the Church and became a traitor to the cause of Zion, an enemy who brought enormous injury and irreparable damage to the Saints and to the Church. Robbed of peace in the Lord, he wrote a letter to Joseph Smith, humbly seeking reconciliation. Here is part of that letter:

I . . . ask my old brethren to forgive me, and though they chasten me to death, yet I will die with them, for their God is my God. The least place with them is enough for me. . . .

. . . I ask forgiveness . . . of all the Saints, for I will do right, God helping me. I want your fellowship; if you cannot grant that, grant me your peace and friendship, for we are brethren, and our communion used to be sweet. [HC 4:142]

Here is part of Joseph Smith’s letter in answer:

Dear Brother Phelps: . . .

. . . We have suffered much in consequence of your behavior—the cup of gall, already full enough for mortals to drink, was indeed filled to overflowing when you turned against us. . . .

However, the cup has been drunk, the will of our Father has been done, and we are yet alive, for which we thank the Lord. And having been delivered from the hands of wicked men by the mercy of our God, we say it is your privilege to be delivered from the powers of the adversary, be brought into the liberty of God’s dear children, and again take your stand among the Saints of the Most High, and by diligence, humility, and love unfeigned, commend yourself to our God, and your God, and to the Church of Jesus Christ.

Believing your confession to be real, and your repentance genuine, I shall be happy once again to give you the right hand of fellowship, and rejoice over the returning prodigal. . . .

”Come on, dear brother, since the war is past,

For friends at first, are friends again at last.”

Yours as ever,

Joseph Smith, Jun.

[HC 4:162–64]

Reconciliation. How marvelous its power. How sweet its blessing.

On the eve of his betrayal, Jesus told his apostles: “All ye shall be offended because of me this night.”

Peter said: “Although all shall be offended, yet will not I.”

Jesus answered prophetically: “Even in this night, before the cock crow twice, thou shalt deny me thrice.”

Peter responded the more vehemently: “If I should die with thee, I will not deny thee in any wise” (Mark 14:27, 29–31).

As you know, that night Judas the traitor led a mob to the Garden of Gethsemane to betray his master, who he knew was there with Peter, James, and John. Peter at first boldly resisted the mob. But once Jesus was arrested, Peter and the others fled. As Jesus was led away, Peter followed at a safe distance. He did not enter the hall where Jesus was accused by false witnesses, buffeted by his accusers, and unjustly condemned to death.

Peter was in a room below, warming himself by the fire, hoping not to be recognized as a follower of Jesus. A woman noticed him and said: “Thou also wast with Jesus of Nazareth.”

Peter denied it and went out on the porch. Hearing a cock’s crow, Peter was no doubt stricken with shame but summoned new resolve. Another woman accused him of being one of the followers of Jesus: “This is one of them.”

Peter’s resolve melted. He denied it again. Now several who had noticed his Galilean accent came over and accused him: “Surely thou art one of them.” This time Peter cursed and swore by an oath: “I know not this man of whom you speak.” The cock’s crow was heard a second time. Realization of what he had done swept over Peter, and he wept. Was not abandoning his master, even denying him, equal to Judas’ betrayal? (See Mark 14:66–72.)

No written records describe Peter’s agony over the next days. Did he stand by helpless as Jesus bore his cross through the streets to Calvary? Was he there as the Roman soldiers drove nails into his master’s hands and feet?

Peter’s story continues after the Resurrection, when the Lord appeared to the apostles, and to Peter in particular gave a sacred trust: “Feed my sheep” (John 21:17). Reconciliation? Oh my! Blessed reconciliation.

For me the message of reconciliation sank deep when my beloved teacher, Manuel Tun, told the parable of the prodigal son in his own words in the Maya language of Yucatán. Allow me to retell it, with adaptations, as he gave it to me.

A father had two sons. I’ll call the younger son Johnny. Johnny’s father was rich. He had hired hands who worked in his fields. Johnny and his brother and father worked hard alongside the hirelings.

To each son the father gave a gold ring to symbolize fidelity to God and to family. Working and talking with his father and brother, Johnny felt contented. His eyes shone, and there was a peaceful expression on his face. He was twelve years old. He was responsible. He was obedient. He was polite and respectful.

Three years passed. He was fifteen now and had new friends. But these boys didn’t like to work. They only liked to play. They teased him: “Johnny, your father takes advantage of you.” And Johnny began to believe them. Often he played all night with them, and in the morning he was too tired to get up and work. He thought: “Why should I work? Why should my father exploit me? I have my own life.”

Quarrels erupted between him and his brother, and unkind feelings developed between Johnny and his father. Now Johnny no longer prayed. He no longer read the word of God. He didn’t like to spend time with his family. At home he felt bored. He didn’t want to work with his father and brother, or even talk with them. He only wanted to play with his friends. He didn’t notice that the warm feeling that was in his heart had disappeared, together with the light that formerly shone in his eyes.

One day his friends said to him: “Your father is rich. Why should you work? Let your father’s hirelings do the work. Go to your father and demand your inheritance. Then you can leave home and be your own boss.”

And Johnny thought: “That’s right! I’ll leave, and I’ll never come back. With my inheritance I can live like a king. I don’t need my family. I’ll live with friends.”

The decision made, Johnny went to his father and said:

“I want my inheritance now! Here’s your ring, your ‘symbol of family unity.’ It has no meaning for me anymore. I’m leaving, and I don’t plan to come back.”

“Your inheritance? You want it now? Johnny, have you thought this over thoroughly?”

“I won’t discuss it, Dad. Just give me my money now!”

Johnny took his inheritance money and left. He made his way to a far city, feeling immensely rich and totally free. Where he went we don’t know, but we can imagine that he went to a place where he was sure no one would recognize him. In the city he found friends, and with them he squandered his inheritance, leading a debauched life. One day he woke up to find that the money that he figured would last forever was all spent. And soon he found that his friends were no friends at all. There was no one who cared for him. He was alone and frightened.

Shortly after the money was all spent, there came a famine, and Johnny began to suffer from hunger. I can just see him standing on a street corner. A cold wind is blowing, and he is clutching a tattered blanket about him. He is hungry, but more than that, he is ashamed. People look on him with pity for the misery he has brought on himself, and children mock him for his wretchedness.

I note the painful expression on his face as he shouts out: “You make fun of me, but my father is richer than you all. Don’t you know who I am?” But no one pays any attention. No one helps.

Now he had lost everything. He had no home, no family, no dignity. He had thrown away everything. In his desperation he thought of sending a letter to his father, asking for money. He still thought money could solve his problems. He did not yet see that the void in his heart could only be filled by reconciliation with his father.

One day a neighbor traveling abroad saw him in this sad state. “So, Johnny, this is where you are. I see you’re in dire straits. Listen, lad, before setting out, I told your father I was coming here. He said: ‘Please, if you happen to see my Johnny, tell him I still love him and want him to come home.’”

“What? Does my father speak of me?”

“Does he speak of you? Every day he speaks of you. Johnny, his heart aches for you.”

“Tell my father I’m okay. I’ll manage.”

But Johnny couldn’t manage. He begged a citizen: “Sir, help me, I am hungry. Give me something to eat.” The man looked on him with pity and gave him work. He sent him into his fields to feed swine.

Emaciated and weak, Johnny ate pig fodder and swill. Soon sick, and with no one there to attend to his desperate need, he cried out in agony: “Oh, God, what have I done? Help me, God. Help me return to my father. I’ll say to him: ‘Father, I am no longer worthy to be called thy son. Make me only as one of thy hired servants.’”

Now Johnny got up and set out for home. I can imagine him walking along dusty roads, climbing hills, descending into valleys, passing through fields and wilderness. He is aching within. Sweat mixed with tears streams down his face, but his every step is quickened by hope.

Nearing his father’s lands, he wondered, “What if Father’s heart has turned against me?” (Oh, but how little he knew of his father’s heart!) How he longed to see his father’s fields. He remembered the happy days of his childhood, pleasant hours spent at play with his brother, times that he was working, playing, singing, and chatting with his dad and mom.

Now Johnny came within sight of his father’s house. His father was standing on a hill from where he could look down on the road. Every day he had stood there, hoping to see if by chance his lost son might be coming up the road. And that day, as always, he was there hoping and praying. Suddenly he saw the figure of a young man approaching. His heart jumped. The boy’s clothes weren’t recognizeable. They were tattered and dirty. The boy was limping. His hair was long and disheveled. But the father recognized his son, and his heart filled with compassion. Johnny had come home! He ran joyously to meet his son and threw himself on his neck and kissed him. “Johnny, my son, you’ve come back!”

But the son said to his father, “Father, I have sinned against God.”

“Yes, Johnny, I know.”

“I have sinned before you, Father.”

“Yes, my son, I know.”

“Oh, I am ashamed, Father. I am no longer worthy to be called your son.”

“Johnny, my son, my son. How terribly you must have suffered.”

The father called to his servants: “Bring clean clothes and dress my son. Put shoes on his feet. Put this ring back on his finger. Come, let us celebrate. For this my son was lost but now is found. This my son was dead but has returned to life.”

There is more to the parable, but I’ll leave it there, adding only a quote from a talk by Elder Bruce D. Porter in general conference.

Like the errant son of the Savior’s parable, we have come to “a far country” (Luke 15:13) separated from our premortal home. Like the prodigal, we share in a divine inheritance, but by our sins we squander a portion thereof and experience a “mighty famine” (v. 14) of spirit. Like him, we learn through painful experience that worldly pleasures and pursuits are of no more worth than the husks of corn that swine eat. We yearn to be reconciled with our Father and return to his home.

How long we have wandered

As strangers in sin,

And cried in the desert for thee!

(”Redeemer of Israel,” Hymns, 1995, no. 6) [Bruce D. Porter, “Redeemer of Israel,” Ensign, November 1995, p. 15]

Another story of the marvel of reconciliation begins in Canaan, which I will paraphrase from Genesis 37–46. Joseph, Jacob’s 11th son, is destined to become a great prophet, and his preparation for that begins early in life when he finds it difficult to get along with his 10 older brothers. Much like Laman and Lemuel with Nephi, they are offended by Joseph and cruelly torment him.

One night 17-year-old Joseph has a prophetic dream. In it he sees a symbolic representation of his brothers bowing down before him. Joseph tells his dream to his brothers. They are infuriated and vow to punish him.

Soon after, Joseph’s 10 older brothers take their father’s flocks to distant fields to feed. Sent by his father to find them, Joseph sets out on a journey of no return. His brothers see him coming, and Simeon, the meanest of them, says: “Here comes the dreamer of dreams. Let’s slay him. We’ll see what will become of his dreams.”

But Reuben, the eldest, says, “Let not our hands shed his blood. Let’s strip him and cast him into a pit here in the wilderness. Then we will be rid of him.” They grab him, strip him, and throw him into a deep pit, intending to leave him there to die.

Joseph has no doubts about their murderous intentions. When they sit down to eat at the top of the pit, he cries out in anguish. But so intense is their hatred that their hearts are unmoved by his desperate cries.

As they are about to abandon him, they see a camel caravan passing nearby. The fourth brother, Judah, says: “What profit is it if we leave our brother to die in the pit? Let not our hand be upon him, for he is our brother and our flesh. Let us sell him.” So they haul the bruised and shaken lad out of the pit and sell him to the caravan merchants for a few pieces of silver.

I can see their dark faces as Joseph stands the last time before them. His eyes move searchingly from face to face as he appeals to them: Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, and the rest—but there is no softening, no mercy. Their faces are resolute, their hearts untouched. They are rid of Joseph forever—or so they think. Little do they realize that this vicious crime against their younger brother will fester in their hearts and rob them of peace until the day of reconciliation.

The terrible deed done, the brothers kill a goat and spatter its blood on Joseph’s coat to take to their father as evidence of his death. Then they take an oath never to even speak of their crime again.

You remember what follows: Taken to Egypt, Joseph is sold as a slave. He finds grace in the house of Potiphar, even becoming overseer over his master’s property. But then, falsely accused, he is cast into a dungeon, where he is doomed to spend many years of his life.

In prison, Joseph’s prophetic powers are made known when he interprets the strange dreams of two fellow prisoners. Later the great pharaoh has troubling dreams that no one can interpret. Learning that a Hebrew prisoner in the dungeon has interpreted dreams, he commands that the prisoner be brought to him. Pharaoh reveals his dreams to Joseph, and God gives Joseph the interpretation thereof: “There shall come seven years of abundant harvest in all the land of Egypt. Then will come seven years of drought that will consume the land.”

Pharaoh sets Joseph as lord over all the land of Egypt. “According to your word shall my people be ruled,” he says. “I only will be greater than you.” Joseph is 30 years old. Thirteen years have passed since he was betrayed by his brothers.

For seven years Egypt is blessed with abundant harvests. Each year grain is stored up against the coming drought. In the eighth year the drought begins, and its suffocating grip begins to be felt in all the land of Egypt. Joseph has storage bins opened up, and grain is dispensed to the people. In the land of Canaan to the north, the drought brings severe hardship. Jacob calls his sons to him and says: “There is grain in Egypt. Go down and buy grain, and bring it here so that we may live and not die.” Joseph’s 10 older brothers go with their donkeys to Egypt to bring grain. Only Benjamin, Joseph’s younger brother, is not allowed to go, because of his father’s fear that some accident might befall him.

Picture in your minds the sight of the 10 brothers leading their donkeys into the hot, dusty square in Egypt. Joseph is there and recognizes his brothers. But they fail to recognize him. He gives orders to have them brought to him privately. Coming before his face, the brothers bow to him with their faces to the earth, not realizing they are fulfilling part of Joseph’s prophetic dream from many years before.

Joseph puts the unsuspecting brothers through a series of trials that humble them. To begin with, after having them confined in a room for three days—figuratively cast into a pit—he has them brought before him. Through an interpreter he commands: “Go, take grain to your families. But until you bring your youngest brother who you say stayed with his father in Canaan, one of you remains here as hostage.” It is Simeon, the most abusive of Joseph’s brothers, whom the guards seize and place in confinement.

Thinking that this great man cannot understand Hebrew, the brothers break their vow of silence: “It is because of our sin against Joseph that God has brought this punishment upon us. When he called out to us from the pit, we saw the anguish of his soul but would not listen. Now his blood will be required of us.” Hearing this, Joseph hurriedly leaves the room to hide his weeping.

Returning to Canaan, they are sustained for a time with the grain brought from Egypt, but when the grain is nearly consumed, Jacob calls his sons to him and says: “You must go again to Egypt and buy grain, lest we perish.” Judah is spokesman for his brothers: “Father, the lord of Egypt said with an oath: ‘If your brother come not with you, you will not be allowed to see my face.’ You must send Benjamin with us. With my own life I guarantee his safe return. If I bring him not back, let me bear the blame forever.”

“Then go, and take Benjamin, that we might live. And may God give you mercy before the great man of Egypt so that he will release Simeon and you will all return home again.”

Now the brothers, including Benjamin, go down to Egypt. As they enter the dusty square, Joseph sees them, and he sees Benjamin is with them. He commands his servants: “Bring these men to my house, release their brother locked in confinement, and make ready a feast for us all.” The startled brothers are ushered to Joseph’s own mansion, Simeon is brought out to them, and they are told that the governor invites them to feast with him. They find no explanation for this. At noon Joseph comes in. His brothers again bow down before him.

Looking at Benjamin, Joseph asks: “Is this your brother of whom you spoke?”

“Yes, it is he.”

“God be gracious to you, my son,” Joseph says, choking up. Again, Joseph hurries out of the room and retires to his chamber to weep where he cannot be heard. After gaining control of his emotions and washing his face, he returns to his brothers, and they feast together.

Before they depart, Joseph gives secret commands to his servants: “Fill their sacks with grain, and put my silver cup in the mouth of the youngest brother’s sack.” When they had gone a short distance with their sacks of grain, Joseph commands his guards: “Go after them, and when you overtake them, say to them: ‘Our master’s silver cup is missing. One of you must have stolen it.’ You will find the cup in the youngest one’s sack.”

The guards catch up to the brothers. To their accusation Judah answers: “We are not thieves. We have stolen nothing. Search our sacks. If you find the cup, let him in whose sack it is found be killed, and the rest of us will be your slaves.” Then, in the order of age from the eldest to the youngest, each takes down his sack to be searched. Alas, there in Benjamin’s sack the silver cup is found.

They are brought back under arrest to Joseph’s mansion. Seeing him, the 11 brothers fall down before him. Through an interpreter Joseph says: “What deed is this that you have done?”

And Judah replies: “What can we say to my lord? How can we clear ourselves? Benjamin and all of us, we are your slaves.”

Joseph says: “Only he in whose sack the cup was found shall remain with me as my slave. The rest of you will return to your father.”

Desperate, Judah speaks: “My lord asked us if we had a father or brother. We answered that we had a father who was old and a child of his old age. One brother is dead, so he alone was left with his father. My lord said: ‘Bring him down to Egypt; if he does not come, you will not see my face.’ When we returned to our father, we said: ‘We cannot go back to Egypt without our brother.’ Our father said: ‘If you take my last son also from me, you will bring my gray hairs with sorrow down to the grave.’ Oh, Great Ruler, when my father sees that our brother is not with us, he will go down in sorrow to the grave. Before setting out on our way here, I said to my father: ‘If I do not bring our brother back to you, then shall I personally bear the blame forever.’ Oh, Great One, how can I go back to my father if I do not bring Benjamin with me? I beg thee, let me stay in his stead as a slave to my lord, and let him return to his father.”

Joseph can hold back no longer. “Let everyone leave. I will speak alone with these men.” All go out—even the interpreter, leaving Joseph alone with his brothers. Now Joseph stands up from his chair before his brothers to speak, but his words will not come out. His voice bursts forth in uncontrolled weeping. Finally he gains control over his emotions and addresses his brothers in Hebrew: “Do you not know who I am?”

There is a long pause as the brothers look at each other in wonder. “I am Joseph. I am your brother.”

His revelation stuns them. They cannot speak. “I am Joseph your brother.” The older brothers are stabbed again with awareness of their terrible crime against their brother. They know they stand convicted before him who now has the power of life and death over them. Surely he will return evil for evil. Heads bowed, they wait for his terrible condemnation. But Joseph speaks softly: “Let your hearts be at ease. God sent me to Egypt and made me ruler in all the land so that I might save your lives. Now, make haste. Go to our father and tell him: ‘Thy son Joseph lives. He is lord of all Egypt.’ Then, all of you, come here with our father and your children and your children’s children. In Egypt I will nourish you and you will be saved.”

Now, one by one, Joseph embraces each of his brothers and they weep together. Such is the miracle of reconciliation, coming to peace. The brothers return to Canaan and tell their father: “Joseph is yet alive. He it is who is lord over all of Egypt.” Then with excruciating agony they confess the terrible secret that has robbed them of peace ever since and tell of the reconciliation with their brother.

What a marvelous preshadowing of Jesus Christ, who would be rejected by his own but whose teachings and atoning sacrifice would open the way to reconciliation with our Father in Heaven.

A story I read long ago helped me see that my words can change someone’s life. It was written by a woman about herself when she was a child just entering first grade. I don’t know the author’s name or where her story was published, but I remember the title: “Seven Words That Changed My Life.” I’ll tell it as I remember it.

Excruciatingly shy, her face disfigured by a cleft palate, and her hearing severely impaired in one ear, Alice lived in self-destructive misery, an invalid in a cocoon of her own making. She had closed herself off from the outside world, feeling unloved and not wanting anyone to see her ugly face or detect her disability. Fearing the inevitable stares and cruel taunts of other children, she panicked at the thought of attending school. How could she hide her ugliness and her deafness? Yet somehow she was made to go to school that first day.

Left early with the teacher, before the other children came, Alice took a seat at the back of the class and hid her face from the others as they came in. After the class began, the teacher announced that they would first have a simple hearing test. One by one the children were to come to the door and stand, waiting until the classroom was absolutely quiet. Holding a hand tightly over one ear and then the other, they were to listen as the teacher whispered something to them. The simple test was to repeat back the teacher’s words.

Alice sat almost in tears. Not only would everyone see her ugly face, but they would find out she was deaf in one ear. She sat with lips quivering as each of the other children passed the test. Now it was her turn to be seen and tested.

Hiding her face in her hands, she walked to the front. Trembling, she turned her face to the wall and covered her good ear, but left enough opening so she could hear the whispered words. Then her teacher spoke seven soft words, words that broke open the floodgates of tears and changed Alice’s life forever: “I wish you were my little girl.”

Do we not all have in our memory times when we have failed to lift up arms that hung down and to strengthen feeble knees, times when by our words or actions we have denied our Lord, times when we have betrayed someone’s trust or looked only to our own needs and wants while slighting the needs of others?

Reconciliation with God is at the core of the gospel. Reconciliation is, after all, the object of the Atonement wrought by the Son of God. Reconciliation with each other through words and acts of kindness and through caring service is also at the core of the gospel. The Master’s life and teachings show us the way.

The Savior said:

If ye . . . desire to come unto me, and rememberest that thy brother hath aught against thee—

Go thy way unto thy brother, and first be reconciled to [him], and then come unto me with full purpose of heart, and I will receive you. [3 Nephi 12:23–24]

Reconciliation is a gift we can and must give to others. It is a gift we can and must receive from others. Ultimately it is a gift we can receive from our Father in Heaven, even being reconciled with him through the Atonement of Jesus Christ.

May we give the gift of reconciliation to others, and may we ourselves receive from our Lord his gift of reconciliation, I pray in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

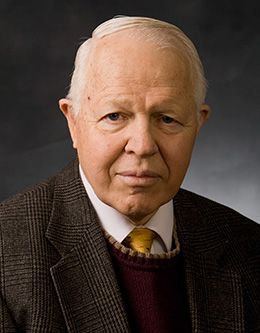

Robert W. Blair was a BYU professor of linguistics when this devotional address was given on 7 July 1998.