Ascending Both Mt. Everest and Mt. Zion: BYU in the Final Decade of the 20th Century

President of Brigham Young University

August 22, 1994

President of Brigham Young University

August 22, 1994

I am so pleased to be with you this morning, and I extend to each of you my warmest welcome as we begin an exciting new school year. I have learned from our friends in Hawaii that the single word that expresses it best is “aloha,” a greeting which I extend to everyone, especially those who join us this year for the first time. I also understand that the word means both hello and goodbye. Accordingly, I extend a warm welcoming aloha to our two newest vice presidents, Alton Wade and Brad Farnsworth, and a fond farewell aloha to Dee Andersen and Ron Hyde, who have been wonderful colleagues and will always be dear friends. And just on the off chance that aloha also means “I look forward to working with you in your new responsibilities, especially as we undertake a capital campaign,” I will bid a fourth aloha to R. J. Snow.

Over this past summer I have found myself reflecting on the fact that as president of BYU I have been doing things for the sixth time. For example, I have attended my sixth annual meeting of the Western Athletic Conference Presidents’ Council, ridden in my sixth Fourth of July parade, participated in my sixth August graduation, and now I’m doing the single most important thing that I do during the sixth or any other year: address the faculty, staff, and administration of the university in our annual fall conference assembly. Because it is the most important talk I give each year, it is also the one responsibility over which I agonize most acutely.

In many ways, it really doesn’t seem like five years have gone by since I assumed my current employment. I have enjoyed it far more than I ever thought I would. There are aspects of what I do that if I had any choice I would do without, but those occupy only a small part of the complete package, and, on the whole, I love my job, I love the institution we serve, and I love the people with whom I work (which includes all of you).

At the outset, I want to pay particular tribute to two groups of people. They have quite different responsibilities, but they share one characteristic in common: We often take for granted and even overlook the indispensable importance of what they do for our university and for us as individuals.

The first group to whom I refer are the members of our board of trustees. With each passing year I have come to love and admire them more. I appreciate their devotion to Brigham Young University and the great trust that they place in us as individuals and in and in our exercise of the stewardship they have given us. They are men and women who understand the challenges of higher education generally—particularly the unique opportunities that we enjoy at this university—and who are dedicated to working with us in a united effort to take maximum advantage of these opportunities. It has been a personal privilege for me to work closely with, and do my best to implement policies crafted by, those we sustain as prophets, seers, and revelators. They are people who care deeply, who strive diligently, whose efforts have directly contributed to the significant progress of recent years, and who have great confidence in us as we work together with them in what President Hinckley so aptly characterized as this grand “Experiment” at BYU.

The second group I single out for particular tribute and appreciation are the members of our supporting staff. I want you to know how much I appreciate, both personally and also on behalf of the university, the many extra-mile services that you so effectively render. Our business is the business of education, and we sometimes tend to think of that in terms of what goes on in the classroom. Such a focus is not only too narrow, it is also simply wrong.

What we do here in attempting to educate our students in an environment of great faith involves a total effort by all of us, and just as Paul observed about the indispensability and inseparability of the various parts of the body, so it is also true that our university could not function without the efforts of all of us. None is more important than the others. I agree with Commissioner Henry B. Eyring that everyone among us is a teacher. And so to those of you who type our letters and scholarly papers, maintain our grounds, prepare our food, repair and maintain our buildings, clean our offices, keep us warm in the winter, cool in the summer, and safe during all seasons, pay our bills, issue our traffic citations, prepare our paychecks, and perform the myriad other tasks without which the classroom and scholarly effort could not go forth, I say, on behalf of all faculty members and administrators: Thank you. And thank you particularly for being here this morning. I do not overlook the importance of what you do, and I invite all those who benefit every day from the services of our staff and auxiliary workers to join with me in expressing appreciation.

The end of five years seems like an appropriate time to attempt to put a few things in historical perspective, looking back over the past five years and also looking forward toward what our aspirations and efforts should be for the next five years and beyond.

About seven months into this five-year period, in February of 1990, I went through a couple of weeks during which I seriously feared that I might not complete even one year. Would that I could have known then what I know now: the lymphoma that I have is not a recurrence of the earlier one, but a very indolent form that can be controlled. In my case it not only has been controlled, but is probably under better control than at any time since first discovered. During our last visit, my principal oncologist in Chicago told me that he looked forward to celebrating my 75th birthday with me. I told him I thought that was a perfectly plausible suggestion, since he is in his midforties and appears to be in good health.

My other physical challenge is a source of irritation and some discomfort but poses no threat either to my life or my ability to perform my responsibilities as your president. I want to give a brief explanation to those of you who are not aware of what it is, because when you observe some of its symptoms, I want you not to be unduly concerned.

It is called peripheral neuropathy, which means a damage to the nerves in my arms and legs. I can no longer run. I have to walk a bit more slowly and deliberately, especially when I first stand after I have been sitting. The neuropathy is accompanied by some pain, which for some reason that no one can explain, is positional. When I stand, I feel practically no pain. Accordingly, when you and I are in a meeting and you see me stand, don’t automatically assume that I do so in disagreement with what you say, I may in fact disagree, but if so I will find some other way to express it.

There have actually been some positive aspects to go along with the aggravations of this neuropathy, as several realities have come into sharper perspective for me. I am now very conscious of and grateful for the fact that for 57 years I had two normal legs that carried me along some of the world’s most beautiful running paths and through 13 marathons, and that for 52 years I enjoyed practically perfect health. To be sure, I wish that I could still bound up the stairs three steps at a time, or run with Janet and my children along the Provo River on a Saturday morning. But far more important is the fact that whereas if I were a dentist, or an architect, or practiced any one of a majority or the physician specialties, or any other calling that required any extensive or specialized use of my hands or legs, I would be unemployed. And that is something that would be much more difficult for me to accept right now than the fact that I will never run another marathon. The only conceivable way that my present employment, which I dearly love, is affected by peripheral neuropathy is that it now takes me about 45 seconds longer to walk from the Smoot Building to the Wilkinson Center. Best of all, whatever its effects, this neuropathy has no potential to affect the real me, which remains very much intact. And what do I mean by the real me? The person who believes, feels, thinks, speaks, makes decisions, travels, and loves life and the work in which I am presently engaged.

Many of you who have known of my neuropathy have asked if there is anything you can do to help. I have appreciated the offer, because it shows that you care. And, as a matter of fact, there is something you can do to help. I want nothing more than for the balance of this decade, which also happens to be the balance of the 20th century, to be the best years that BYU has ever had. For reasons I will discuss in more detail, I have every confidence that they can, should, and probably will be the best years of our first 125. And nothing would help me personally—both physically and otherwise—quite like seeing us achieve such a standard of excellence in our citizenship, our teaching, our scholarship, our support services, and in everything we do.

Let me turn, then, to some specific ways in which I think we can make these next few years the best in BYU’s history.

When I refer to our history, I am sobered by the realization that the period of my own association with this place covers more than a third of our total years from Warren Dusenberry to 1994. There are many differences between today’s BYU and the on in which I enrolled as a freshman living in converted army barracks known as the “D” dorms in the fall of 1953.

While in most respects this is a much better university than the one in which I enrolled four decades ago, there are some parts of the BYU of the 1950s that I wish we could bring back. And there is one of them that we are in fact going to make a major effort to revive during this coming year. We invite your participation in that effort, because without your participation, it will not succeed. It has to do with our attendance at devotionals and forums. For those of you who were not here during those earlier times, let me tell you how it was in “the good ol’ days.” Two principal features are relevant.

The first is the regularity with which those assemblies were held. Every Tuesday at the same hour, I believe it was 10 a.m., we held a devotional or forum assembly. And the second feature was, I think, at least partially attributable to this regularity. The great majority of us—students, faculty, staff, everyone—simply assumed that attendance at these devotionals and forums was what we did at that particular hour every week. When a devotional or a forum was held, we were there in attendance at the Fieldhouse. I can see now in retrospect even more clearly than I could at the time that there were some significant benefits to the university and its people beyond the most obvious and important one, the substantive spiritual and intellectual development that we gained from the content of those addresses. It gave us a sense of community, a sense of belonging. In addition to being members of a ward or a social unit, and students sharing majors in a particular department, we were also participants in, and even owners of, the entire larger enterprise, Brigham Young University. I recognize that that sense of university community is not absent from the BYU of the 1990s. It is here, stronger than at most other universities, and probably stronger than at any other of our size. But it is not what it used to be. More importantly, it is not what it can be. We are convinced that one of the most important things we can do to strengthen this sense of oneness that reaches across 27,000 students and 5,000 faculty and staff is to join together in greater numbers and with greater purpose in the only university-wide events under university sponsorship, our devotional and forum assemblies.

As you know, in recent months we have broadened our devotional program to include campus devotionals, featuring members of our own faculty, with each particular campus devotional sponsored by the college from which the speakers comes. They are held in the de Jong Concert Hall. Like the university devotionals and forums, of which there are five or six a semester held here in the Marriott Center, these campus devotionals have been held Tuesdays at 11 a.m. We have been very pleased with them, and we plan not only to continue them, but also to expand their number. The result will be that when combined with the forums and university devotionals held in the Marriott Center, and a few other programs of selected interest, we will meet as an entire university every Tuesday at 11 a.m. Our hope is that across the entire campus, all of us will simply come to assume that the thing to do—and what we in fact do—every Tuesday at 11 a.m. is to attend the devotional or forum or other program that is being offered that week.

If the effort is to be successful, more will be required than simply regularizing the schedule. There are things that every one of us can do, but the key players will be the faculty. There are so many ways that those who teach our classes can enhance not only the attendance at these events, but also the quality of the learning experiences they offer. Some of you are already doing some things that I would like to see become much more widespread. For example, there are some of you who assign students to attend the devotionals and forums and to report on what was said, including their reactions and responses. Others of you have made arrangements to attend the devotionals with your students.

Most of you will be serving this year as faculty mentors for a small number of students. This faculty mentor program, in my opinion, will be highly beneficial to our freshman students in so many respects, including, principally, helping them to adjust to a new life at BYU. I hope that you will include these students for whom you serve as mentor in your plans to attend forums and devotionals.

Different ones of you may elect different approaches, whether attending with your classes, attending with the students you mentor, making assignments for reports, or some other. But whatever the method, I hope that every one of us will do something that will involve not just our own attendance, but our students’ as well.

Over the coming year I would like to hear from you concerning your efforts to improve our forum and devotional attendance. Nothing would please me more than to receive so many reports that it becomes difficult for me to respond to each. The first of these Tuesday-at-11:00 a.m.-events will be on September 6, which will feature a special performance by the Young Ambassadors in the de Jong Concert Hall. The following week, September 13, will be our first university devotional.

Last year the subject to which I gave most attention in this address was our effort to enhance the quality of our students’ learning by assisting them in their efforts to graduate in four years. I reviewed a variety of initiatives to be pursued during the 1993–94 school year, most of which involved nonfinancial efforts. I also reviewed some possible financial reforms. Under the general leadership of John Tanner, and with cooperation from the faculty that can only be described as remarkable, very impressive progress has been made over the ensuing 12 months. This has included curricular reform; mandatory counseling, including the filing of graduation plans for students in certain categories; articulation agreements with certain feeder schools; increasing the number of sections of certain required courses after the existing sections have been filled during the registration process; and increased scholarships for students attending spring and summer. And for the coming year our spring/summer tuition will be reduced by 27.5 percent. It will be the most extraordinary tuition change in BYU’s history.

One common feature of several of these initiatives involves an attempt to shift more of our students and more of our classes into the spring/summer terms, when we are well below the 27,000 limit, and away from the fall/winter semesters, when our airplane is full. I fully expect another quantum increase in this respect during this coming school year because of the tuition decrease. This will necessarily require some planning on our part and yours, as well as a certain amount of guesswork and good luck as we anticipate the degree of those increases and the consequent surge in the required number of course offerings and teachers. We have already seen some results from the graduation initiative. For example, the average number of semesters for our April and August graduates has declined from just under 12 semesters to just over 11. I strongly doubt that these results are pure coincidence. And most of our positive effect surely lie ahead of us, because most of the steps we have taken will require more than a year to yield their results.

Our efforts to improve our graduation time will, of course, continue over the coming year, as will several other efforts presently underway. May I now devote the rest of my time to discussing two initiatives that are new this year. While each of them has been on the drawing boards for three or four years and is the product of substantial previous investment, each was actually launched during 1994; the coming school year will mark the first full 12-month term for each. The two are related in that each involves an attempt to achieve objectives that will last beyond our present decade. One of them, the capital campaign, will involve substantial numbers of us. The other, our strategic long-range planning, will involve virtually all of us—staff, faculty, administrators, everybody. I would like to discuss our long-range planning first.

Our every common sense instinct tells us that long-range planning is something that has to be done and that it is especially crucial for an organization as complex, as resource-consumptive, and as diverse from one department to another as is our university. Actually, to one degree or another, we all do strategic planning. Whether consciously or unconsciously, we do it for ourselves personally, for our families, and for our employment. We pay attention not only to what is happening here and now, but also what the future may hold and what we can do now to make our future better. Equally clearly, long-range planning works better if it is done systematically and is itself the result of a planned effort.

As obvious as are the need and potential benefits, carrying it out is not always correspondingly simple. Many times adjustments have to be made to the original plans in light of subsequent events. Let me give you two examples that illustrate the point, one taken from the early history of our country, and the other from my own personal history.

In the early part of the 16th century, there was a map (prepared initially by Spanish cartographers) that was used throughout Europe. It portrayed California as an island, and, indeed, labeled that part of the Americas as the Island of California. Here is a copy of that map. [slide] It was widely used and regarded as unquestionably authentic. With each passing year, the degree of its assumed authenticity increased. The cartographers who developed the map relied on two established facts. One was that Spanish navigators had sailed up what we now refer to as the Gulf of California for many miles and found no end point. Similarly, other navigators had sailed down Puget Sound with similar results: no end in sight. The logical conclusion: California was an island. Accordingly, when the time came for inland exploration from California, the explorers concluded that of course they would have to carry with them necessary materials and equipment to build a ship. The absolutely amazing part of the story, as I heard it from Peter Schwartz, an expert on long-range planning and author of a book called The Art of the Long View, is that when the explorers—after having carried all those tons of extra weight across the Sierras and into the desert—sent word back to Spain that the map was wrong, the response was that the map was not wrong. It had been in existence for many years, and it was therefore the explorers who erred.

The other example is my own. Undoubtedly, all of us engage in some form of personal long-range planning, and I am no exception. Once I finished law school and a one-year judicial clerkship, I laid out for myself a broad, general long-range plan: I would practice law in Phoenix, raise my family in Tempe, serve the Lord in whatever capacity I could, and be active in Arizona political and civic matters. That plan worked for eight years. Since then I have had four separate and quite different professional experiences, two of them here at BYU and two at the United States Department of Justice. Each of the four, standing alone, has been more fulfilling and more interesting than anything that was included in my 1964 personal long-range plan. And in 1964 I had no way of knowing that events might lead to any of those opportunities.

The message that evolves from each of these examples is not that long-range planning doesn’t work or is something not to be undertaken because the costs outweigh the benefits. Quite the contrary. Strategic planning is not only a good idea, we all do it—it will happen. The only real issue is whether we do it consciously and systematically, devoting to it the amount of time, attention, and other resources that it deserves because of its potential benefits. But it is necessarily iterative. It must include the ability to adapt to new facts and new circumstances as they develop, and will necessarily involve much dialogue and broad participation. Indeed, the process itself will be a principal source of such new information.

Many details of BYU’s long-range plan, including the background out of which it arose and how we intend to implement it, have been reviewed by our provost; have been matters of discussion with vice presidents, executive directors, and deans this past week; and will be discussed with the faculty tomorrow morning and with department chairs tomorrow afternoon. To those discussions let me offer a few additional thoughts.

1. My first observation is that nothing is more important to the university than to plan today for what we want to be in the future, and what it will take to get us there. The initiatives that are already underway, such as the efforts to improve our graduation time and our capital campaign, have not only been important preparation for, but will also become part of, the long-term planning effort we now begin. Already completed projects, such as our academic freedom statement and our standards for employment and for promotion and tenure, are established premises on which we will build our long-range planning discussions and work.

2. Two years from now, 1996, is the year of our decennial accreditation inspection, in connection with which we are required to prepare an institutional self-study. That self-study will be integrated with our strategic planning, and certain efficiencies will be achieved by combining the two. We want to emphasize, however, that our long-range planning will not end in 1996, and the accreditation self-study is only a part of the larger whole. And 1996 is also the target date for beginning to reflect the institutional priorities developed through our planning efforts in our budget planning, preparation, and submission.

3. What we are dealing with here is not an undertaking by the university administration, but by every one of us, faculty, staff, and administration. And the success of the endeavor depends on our recognition of that fact. The premise from which the entire effort must proceed is that each of us will participate in the process, and each will benefit from its results. The process will involve three basic phases: assessing what we have become; determining where we want to be in the next five years to ten years and deriving criteria for achieving those goals; and applying those criteria to our critical decisions. We need to be thinking now and planning for the future with regard to such important issues as, for example, (a) how we allocate our 27,000 admissions slots to maximize our ability to provide a better education and better serve the worldwide kingdom; (b) how we can, through our continuing educations efforts and otherwise, extend BYU’s influence and blessings beyond our two campuses; and (c) what we ought to do to assure that our capacity and understanding regarding non-English languages and non-American cultures fit more beneficially within the broader Church that is expanding so rapidly, so broadly, and so effectively throughout the world. We are not a Utah university, and our sponsor is neither a Utah nor an American church. How can we more effectively join our boxcar to the Church’s international train? These are only examples. It will not be easy, but if we do it right the benefits will far outweigh the costs. It was Abraham Lincoln who said, “I will prepare myself, and when the time comes I will be ready.”

4. This strategic planning initiative necessarily deals with the kinds of issues concerning which the members of our board of trustees are not only intensely interested, they also must make the final decisions. Accordingly, throughout its entire course, the board will be involved in this process. In the meetings to be held tomorrow with the faculty and department chairs, you will be given further details concerning the timetable for involvement by the board and others.

5. If we succeed in this effort, one of the results will be that by the turn of the century our resources will match up better with where we as a university and each of our constituent units have unitedly determined we want to go. Much of the important realignment of resources with carefully specified and articulated goals will occur within departments and comparable administrative units. That is, the realignment will be internal. While there are important institution-wide elements in the planning process, we are inviting each of you in your respective departments and administrative units to clarify objectives and to use the resources—human and financial—now available to you to advance those purposes and objectives. At the university level, we intend to enhance intradepartmental reallocations. We will invest in programs, activities, and areas consistent with university-wide priorities where there is the promise of the greatest payoff for our students and where we can best advance our long-range goals and purposes. Some of the resources for these enhancements will come from reallocations within the overall university budget. But we are also launching a capital campaign, concerning which I will have more to say in a moment, whose purpose is to make funds available to advance clearly articulated institutional priorities.

6. There are some important linkages between our strategic planning initiative and our capital campaign. One is that the development of our capital campaign priorities was itself an example of classic long-range planning, and those priorities should figure prominently in our strategic planning. Moreover, during the silent phase of the campaign, which I will describe in just a moment, we will clarify and solidify those priorities through further planning efforts that will involve many of you and will be part of our total strategic planning. And the “public phase,” which I will also discuss in a moment, is scheduled to begin after this year’s self-study, whose planning efforts will have further clarified our institutional priorities. Thus, the timing between the public phase and the completion of our statement of priorities should coincide quite nicely. Finally, the funds that we will raise during the campaign will be important in enabling us to implement the strategic plan we develop.

I turn, then, to a discussion of our capital campaign. Planning for this campaign began a little over three years ago, when Ron Hyde and Dennis Thomson interviewed the leadership in each college in order to prepare what we called a financial needs assessment. The purpose of that assessment was to ascertain how, where, and for what purposes additional funds could be most effectively utilized if such funds were available. It is not surprising that the total amount of money which would have been necessary to satisfy that initial needs assessment far exceeded our fund-raising capacity. Accordingly, the next step involved determining which of those needs had greatest priority, in order to bring the total figure within our reasonable reach.

The priorities that emerged were tested by independent consultants, through extensive and intensive interviews that they conducted last summer and fall. Based on their study, they advised that a properly conducted campaign over the six remaining years of this decade could feasibly raise over $200 million. And that is our goal. It is, by some margin, the largest such campaign ever undertaken at BYU. With commensurate substantial benefits, both over the near term and into the next century. We project that over the six-year period some 325,000 donors will contribute. Over half of the funds will come from less than 50 of those people, but participation by all of the larger number will be essential. Particularly important, in my view, will be the participation by every one of us. I hope that through our Together for Greatness contributions and otherwise we will lead the way, if not in the size of our gifts, at least in our willingness to make a sacrificial participation. Beginning with this year, the opening year of the capital campaign, I plan to increase my own Together for Greatness contribution, and I invite each of you, in light of your own particular circumstances, to consider doing the same. I am convinced that a significant increase this year in our Together for Greatness contributions will yield returns far beyond the amount of those increases, because other donors will be impressed by the fact that we are leading the way toward the success of this campaign.

For the next two years, sometimes called the “silent phase” of the campaign, we will concentrate on large “lead” gifts and on planning for the second phase, sometimes called the “public phase.” We will publicly announce this second phase in 1996, at which time we will begin our concentration on larger numbers of people. I felt it appropriate to share with you today information about the campaign even though we are still in the preliminary silent phase, because many of you will be involved in the planning and other activities that will occur over that time, and also because I want all of our BYU community to have a knowledge now of this campaign that will affect all of us in such important ways.

The campaign priorities include three broad categories: (1) teaching more students, (2) enhancing our educational quality, and (3) securing future opportunities. The first relates to our graduation initiative. Most of the steps that need to be taken in this respect involve nonfinancial efforts as discussed earlier. But there are also some ways in which additional funds can help, including financial aid to students, particularly those who are willing to attend spring and summer; additional faculty and other teaching resources necessary to accommodate anticipated increases in spring/summer loads; and an increase in the number of high-demand General Education sections. It came as no surprise that our consultants’ study revealed that the areas of gift opportunities that drew the most enthusiastic comments were those projects that would increase access for more students to the BYU experience.

The second priority category, improving the quality of our teaching and generally enhancing the value of our educational offering, includes such things as our library expansion, building BYU’s primary role as a superior teaching institution, supporting faculty scholarship that enhances teaching and serves Church interests, endowing operation of the Museum of Art, and extending practical and supplementary education to the members of the Church through distance learning and opportunities.

The third category—securing future opportunities—includes building our endowment and enhancing our international mission. Very simply, the gap between our potential and what we have done is probably greater with regard to our international opportunities than in any other area. Because of the extensive language capacity of our students, and because of our sponsorship by a Church that is expanding so rapidly into so many areas of the world, international opportunities constitute our great potential comparative advantage, and to date we have only scratched its surface. In this area as in others, our capital campaign should enhance our capacity to come closer to realizing our potential.

Through the course of this six-year campaign, we should all keep in mind three general considerations.

First, as we will be explaining to each of the deans in individual meetings, every college should participate in and benefit from this campaign. Some of the specific priority subcategories pertain to particular colleges, such as the Religious Studies Center, the Center for Studies of the Family, the Center for Entrepreneurship, the Institute for Language Studies, and scholarships for students committed to teaching as a career. Others, such as funds for the Faculty Center, the libraries, and the Museum of Art, are committed for particular purposes, but their benefits will be felt throughout the entire university, affecting every college. But the most important point to note is that over half of the funds to be raised have not been earmarked for any particular college or department. An important part of the planning process that will take place over the next two years will involve consultation with the deans and others concerning how each college, and the programs in those colleges, will be involved in and can benefit from our capital campaign.

Second, not all of the funds from this campaign will be available either immediately or even at the end of six years. The principal reason is that many of these donations will be in the form of deferred gifts. That is, while the obligation is fixed and vested, the receipt of the proceeds will be deferred until the occurrence of some future event.

Finally, if it is to succeed, the entire effort must be carefully coordinated and confined to the stated campaign priorities or to those few additional needs that may arise during the course of the campaign for which a compelling case can be made for a midcampaign adjustment to the priorities. Experience and common sense teach that the effort must be a unified one, which does not permit independent, non-coordinated efforts by particular units within the university. In short, over the next six years, if anyone at BYU is going to raise money, it must be done as part of the capital campaign.

Both of these initiatives, our strategic planning effort and our capital campaign, have as their principal and common objective to bring us to the kind of university that we want to become and that we can become. May I close with just a couple of general thoughts concerning the university for which we strive.

An article in a recent edition of the Chronicle of Higher Education discussed the renewed interest in and debate over whether religion has any role to play in higher education. Relevant to that issue, George Marsden, professor of history at Notre Dame, in an article entitled “Pluralism, Yes. Religion, No!” recounts a conversation with a political scientist who opined that “if a professor proposed to study something from a Catholic or Protestant point of view, it would be treated like proposing something from a Martian point of view.” Professor Marsden then expresses his own contrasting opinion:

One of the great strengths of American academic life is its diversity of opinion. Unfortunately, with respect to religion in academia, “pluralism” and “diversity” have become code words for their opposite—exclusion and uniformity. While universities say they welcome diverse cultures, they do not welcome the distinctly religious dimensions of those cultures.

There is, of course, no question where we come down on that debate over the value of religion in higher education. And we have much that we can contribute, precisely because our religion is different. We are unalterably committed to carrying out our conviction that not only are faith and intellect not mutual antagonists, they are synergistic. Each provides a source of knowledge and a means of learning.

We have not and we will not depart from President Kimball’s great vision stated in his Second Century address that among universities BYU must become a Mount Everest. That does not mean, of course, that our mountain will look exactly like everyone else’s. Most importantly, our mountain must include not only elements of Mount Everest, but also Mount Zion. Mount Everest is notable because of its height and size, things we can measure, things that the world can see, and things that the world recognizes. Mount Zion is distinctive because of the nobility of the hearts and souls of people who live there. The two are not inconsistent, and each is important. They complement each other nicely, and that is what makes our university both unique and valuable.

The first sentence of our mission statement proclaims that our mission is “to assist individuals in their quest for perfection and eternal life.” The second sentence further clarifies that “that assistance should provide a period of intensive learning in a stimulating setting where a commitment to excellence is expected and the full realization of human potential is pursued.” I am convinced that our ability to accomplish these objectives and more generally to contribute to the building of the kingdom in ways that we are uniquely qualified to offer is directly proportionate to our establishing ourselves as an excellent university, measured by the same rigorous standards applicable to all good universities. And it is just as clear that if we concentrate only on those objectives important to other universities, we will have sacrificed our unique opportunity to contribute to the restored gospel and to American higher education and indeed will have given up our very reason for being. If we are to do our job right, we must be both competent and faithful. Neither alone is sufficient.

What wonderful years lie ahead of us. I think that never in my life have I been quite as excited and enthused as I am right now about what lies ahead, both for me personally and for the institution with which I am affiliated. The excitement reaches across a broad range of things that I see on our horizon carrying such large potential for the future of our university. And because the future promise for our university is so significant, it is equally significant for the broader restored kingdom of which we are an integral part. The years to come will be years of strategic planning, of a capital campaign that will help bring to reality key aspects of that planning—years in which we will continue to build on established accomplishments of the past and years in which we will increase the number of students we an admit each year while still working within our 27,000 student enrollment cap.

There is so much good that we can do for our students, for our Heavenly Father’s children throughout the world, and for ourselves in our efforts to achieve eternal life. We cannot realize those potentials unless we are very good at what we do—good teachers, good scholars, good in carrying out our support services, and totally dedicated to the principles of the Restoration and the integration of those principles into everything we do. I hope that you share my excitement and my enthusiasm for the task as we come closer to Mount Everest and Mount Zion. That the Lord himself may be our partner in this effort, that he may in fact, in the words of Alma, “give us strength according to our faith,” is my prayer in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

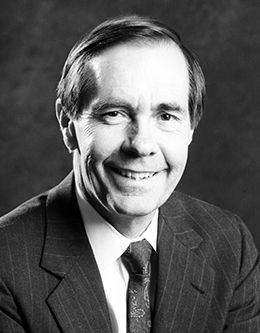

Rex E. Lee was the president of Brigham Young University when this Annual University Conference address was delivered on 22 August 1994.