The Transformative Power of Faith and Art

Associate Director at the BYU Museum of Art

March 9, 2021

Associate Director at the BYU Museum of Art

March 9, 2021

Faith that is “tested, wounded, but . . . here” is a powerful, transformative kind of faith. That kind of faith recognizes that because we look through a glass, darkly, we will still have questions. It is a faith that coexists with questions and paradoxes. It is a faith that has battle scars but also enduring resonance.

It is an incredible honor to be here today. Thank you to those of you who are here in person and who are listening online. BYU devotionals and forums are a unique and wonderful part of our campus traditions, and I am humbled and grateful to be a part of them. In my career as an art historian and museum professional, I have had the great privilege of learning from art and artists of the past and present. Today I would like to share some of the insights, both secular and spiritual, that I have learned through my field of study.

I would like to begin with a quote from French artist Rosa Bonheur, perhaps the most successful female painter of the nineteenth century. Near the end of her career, Bonheur declared: “My whole life has been devoted to improving my work and keeping alive the Creator’s spark in my soul. Each of us has a spark, and we’ve all got to account for what we do.”1 Bonheur’s spark led her to paint, despite enormous obstacles and cultural restrictions, and to paint what she loved, which was animals. Her impressive painting The Horse Fair, exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1853, is part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection. Through it, her bold determination to be true to herself and to that spark inside her opened the doors of possibility for later generations of women.

What are we doing to keep the Creator’s spark alive in our souls? How are we improving our work and our abilities?

We all have unique gifts and skills. Your time at the university is an incredible opportunity to investigate, experiment with, and develop those gifts. The truth is that this search for your place, for excellence, and for your particular aptitudes will be a lifelong pursuit. While not all of us are artists, all of us need both creativity and inspiration to find our way. I believe that the arts and the gospel can guide us as we go, providing fresh perspectives, new ways of looking, and much needed reassurance. In 1 Corinthians 13:12, Paul said to the believers in Corinth, “For now we see through a glass, darkly” (emphasis added). His words underscore one of the great obstacles of life: we have limited understanding and perceptions. We must daily assess the best courses of action while seeing through darkened, obscured glass.

This week marks exactly one year from the time that things shut down in the United States due to the COVID-19 pandemic. What a year this has been—unexpected and challenging, a time of uncertainty, isolation, and often loneliness. Beyond the pandemic, this past year has been fraught with weighty and monumental issues such as racial turmoil, political acrimony, and disturbing incivility. At the beginning of the year, President Kevin J Worthen summarized 2020 succinctly as “COVID and chaos.”2 These circumstances can feel daunting and overwhelming.

Here on earth, it is easy to feel a bit like the disciples in Mark 4:37–40. They were in a boat during a raging storm that threatened to overwhelm them, and the Savior was sleeping. “And he was in the hinder part of the ship, asleep on a pillow: and they awake him, and say unto him, Master, carest thou not that we perish?” (Mark 4:38; emphasis added).

I think this story resonates with all of us. Sometimes we think, Don’t you care that this is happening to me? Don’t you see that my dreams are being crushed? Don’t you know that my family member is so ill or that I have lost my job or that my marriage is struggling? Don’t you see that this addiction or infertility or death of a loved one is killing me? We each may insert whatever it is that we are struggling with at the moment. I know that in my own life it is easy to become convinced, however momentarily, of a sleeping God. We rashly jump to the conclusion that He either does not know—the equivalent of sleeping—or does not care. Master, carest thou not that we perish?

But in the biblical account, that is not the end of the story. In Mark 4:39–40 we read:

And he arose, and rebuked the wind, and said unto the sea, Peace, be still. And the wind ceased, and there was a great calm.

And he said unto them, Why are ye so fearful? how is it that ye have no faith? [emphasis added]

This moment, as illustrated in Arnold Friberg’s painting Peace, Be Still, shows the darkness and drama still around the Savior as He, full of calm and light, stills the storm. Faith, despite the circumstances, is the crux, isn’t it?

Holocaust survivor and Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel, who passed away in 2016, wrote about his experience in concentration camps during World War II in his first book, Night. This slim but powerful memoir, which has been translated into thirty languages, had a formative impact on my understanding of the complexity of faith and the mysteries of God when I first read it many years ago. Much of the book revolves around man’s extreme inhumanity to man and the apparent absence of God.

Upon his arrival in Auschwitz, Wiesel and his father were separated from his mother and three sisters, half of whom he would never see again, and he saw young children being sent to the gas chambers. In his words:

Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, that turned my life into one long night seven times sealed. . . .

Never shall I forget the small faces of the children whose bodies I saw transformed into smoke under a silent sky.

Never shall I forget those flames that consumed my faith forever. . . .

Never shall I forget those moments that murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to ashes.3

When he watched a young boy die slowly by hanging and repeated the question posed by someone in the crowd—“Where is God?”—Wiesel wrote, “And from within me, I heard a voice answer: ‘Where He is? This is where—hanging here from this gallows . . .’”4

One would not, I believe, be surprised at this reaction. When faced with such horrific circumstances in which God does not intervene, many turn away from Him or conclude He does not exist. Indeed, grappling with the reality of evil has been the focus of much philosophical and theological debate for centuries. While it is likely that none of us here have lost family members in gas chambers or survived the torture of concentration camps, I believe that something in Wiesel’s words may reflect our own feelings. There are times when our faith feels consumed or when our dreams have turned to ashes.

But for Wiesel, the darkness of evil and the absence of God was not the end of his story either. In his own words, he later clarified:

Some people who read my first book, Night, they were convinced that I broke with the faith and broke with God. Not at all. I never divorced God. It is because I believed in God that I was angry at God, and still am. But my faith is tested, wounded, but it’s here. So whatever I say, it’s always from inside faith, even when I speak the way occasionally I do about the problems I had, questions I had.5

Faith that is “tested, wounded, but . . . here” is a powerful, transformative kind of faith. That kind of faith recognizes that because we look through a glass, darkly, we will still have questions. It is a faith that coexists with questions and paradoxes. It is a faith that has battle scars but also enduring resonance. It reminds me of a poem by Emily Dickinson in which she imagined a time in the future when she would have a personal interview—a conversation, if you will—with the Savior. She wrote:

I shall know why—when Time is over—

And I have ceased to wonder why—

Christ will explain each separate anguish

In the fair schoolroom of the sky—

He will tell me what “Peter” promised—

And I—for wonder at his woe—

I shall forget the drop of Anguish

That scalds me now—that scalds me now!6

Indeed, “scalded” is a poignantly descriptive way to describe our personal heartbreaks. I have thought long and hard for many years about the Lord’s requirement of a broken heart.7 The need for a humble, contrite heart seems perfectly clear and reasonable to me, but a broken heart? I would prefer that the Lord ask for a softened heart (which He does) or a receptive heart (which He also does) or even a heart stretched perhaps three sizes in one day (Dr. Seussian Grinch style!), but why broken? That sounds painful and even irreparable. And yet—and yet—it might also sound familiar to each of us.

Life has a way of giving us the unexpected, of presenting challenges that figuratively break or shatter our hearts. In my own life, as with many of you, I suspect, I have faced trials that have taken my breath away. One quite visible one is remaining single and childless despite all of my best efforts and living in a culture that values, both practically and doctrinally, marriage and family above all else. This, at times, has been quite painful. Over the years I have determined that God does not want our unhappiness and heartbreak, but it is because He knows that life experiences will wound all of us that He says, “Come to me with a broken heart and a contrite spirit.” The world likes us when we are confident, successful, and good-looking and have all the answers.8 In contrast, the Lord wants our most authentic self, the good and the ugly; the self that may have fallen and is struggling to get up; and the self that can’t understand or make sense of the messiness of life and the inexplicable anguish.

I believe that it is in these moments of sorrow that we come to know ourselves and what matters most. From my personal experiences, I feel much greater compassion for those who struggle and experience hardship. Let me invite all of us, during those moments that wound our souls and our faith, to remember Him who “was wounded for our transgressions, [and] was bruised for our iniquities” (Isaiah 53:5). Isaiah described the Savior as one who was “a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief” (Isaiah 53:3). He can walk with us in our grief and with our broken hearts. What we will find, over time, is that as we go, faith that seemed dead and hearts that seemed broken beyond repair begin to live and beat again. It is, in my mind, a resurrection of sorts—a resurrection with a lowercase r that aids our understanding of the concept that that which is dead can be given new life. Indeed, the Lord has promised us a gift of “a new heart” (Ezekiel 36:26).

This new heart allows us to feel more empathy and compassion than before. A great part of our Christian commission is “to bear one another’s burdens . . . ; . . . to mourn with those that mourn; yea, and comfort those that stand in need of comfort” (Mosiah 18:8–9). At times this can feel natural and even easy, but the making of a new heart is no simple transition. Christ is not just asking us to become slightly better, although we must do that; He is asking what seems almost unthinkable—to “love [our] enemies, bless them that curse [us], do good to them that hate [us], and pray for them which despitefully use [us], and persecute [us]” (Matthew 5:44).

How do we get to this point? I freely admit to you that I am not an expert on this subject; I am a fellow traveler on this transformative path. But I believe that Harper Lee’s simple formula in To Kill a Mockingbird applies. Atticus Finch told his daughter, Scout:

If you can learn a simple trick, Scout, you’ll get along a lot better with all kinds of folks. You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view— . . . until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.9

In my life, art has often been a way to see the world from a new perspective, a version of climbing inside someone else’s skin. It can teach, heal, and inspire; likewise, it can also shock, push, and transform our thinking. Some artists teach us about experiences that we can’t possibly have on our own. As a White woman from Utah, I am personally untouched by genocide, war, extreme poverty, and racism. Art has been a powerful tool in my personal understanding of some of these experiences.

For example, Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial, located in Washington, DC, helps us understand war and loss. Designed when she was a twenty-one-year-old undergraduate at Yale University, Lin placed two black granite walls together in a V-shape, inscribed with the names of more than 58,000 deceased soldiers. Her work was immediately controversial because it lacked the heroic feel of past war memorials, which typically were made of white marble and focused on military leaders. By contrast, her vision honors all of the fallen, and it was based on imagining two cuts into the land, like a “wound that is closed and healing.”10 The highly reflective surface allows you and your surroundings to also become part of the work when you visit. Over time, this has become a beloved and sacred site—a place to leave flowers, make rubbings of family names, and consider, when walking past the accumulation of thousands of names, the cost of war on individuals, families, and our nation.

Dorothea Lange’s black-and-white photographs, such as Migrant Mother, and Maynard Dixon’s Forgotten Man are haunting reminders of life during the Great Depression in the 1930s. As we look at them, we feel the weight of the problems of that time, and we are invited to ponder, Whom among us hasn’t felt like they are metaphorically alone on the curb with life passing them by? As we examine the individuals in these images, they cease to be “other” and separate from us and rather represent all of us at different times. In the words of Mosiah, “Are we not all beggars? Do we not all depend upon the same Being, even God, for all the substance which we have . . . ?” (Mosiah 4:19). Dixon’s Forgotten Man hangs in the BYU Museum of Art’s permanent collection; it has been the source of many insightful conversations with students and museum patrons about compassion, depression, and the courage it takes to really see those around us, unlike the busy crowd that bustles on in the background.

Pulitzer Prize finalist, author, and art critic Lawrence Weschler wrote movingly about the power of art to heal and about art as a balm to the soul. As part of an assignment to cover the Yugoslavian war crimes tribunal in The Hague in the 1990s, Weschler met with a judge who daily was dealing with accounts of murder, rape, and horrific torture. In response to Weschler’s query about how he could hear such things without going mad himself, the judge answered that as often as possible, he walked over to the Mauritshuis museum to see the Vermeers. The paintings radiate, in his words, “a centeredness, a peacefulness, a serenity.”11 As Weschler pondered on this and studied the paintings Johannes Vermeer created in the seventeenth century, he observed that they provided a unique and timely parallel, in that when they were painted,

all Europe was Bosnia (or had only just recently ceased to be): awash in incredibly vicious wars of religious persecution and proto-nationalist formation, . . . replete with sieges and famines and massacres . . . and wholesale devastation.12

Vermeer’s paintings, as many scholars have noted, specifically avoid any of this turbulence and instability. Instead, the artist repeatedly gave us a small room—usually with a woman quietly going about daily tasks—that is an intimate domestic space filled with light, calm, and peace. It is a peace generated in his imagination, a product of his own creativity. These luminous, serene scenes are gifts to the world and, centuries later, an antidote to anyone suffering from anxiety and turmoil.

Art also offers wonder, unrestrained awe, and joy. North Carolina artist Patrick Dougherty creates monumental sculptures out of thin, malleable saplings. In a recent exhibition at the BYU Museum of Art in 2018, Dougherty created a work inspired by the majesty of our mountains and the arches of our national parks, resulting in a space of dreams and whimsy that connected visitors to nature and their own childhood wonder. Mexican-born, Dallas-based artist Gabriel Dawe uses thread, the everyday material of our clothing, to create site-specific installations using all of the colors in the light spectrum. Plexus 29, in the Lied Gallery of the Museum of Art, uses almost eighty miles of vibrantly colored thread woven together to create a unified network—or plexus—that invites us to contemplate the transcendent power of light and our interconnected relationships.

One of the things that I am appreciating more about art recently is the wide range of creativity in the world and our need for different voices. One artist may feel intensely compelled to use their art to shed light on injustice and gender inequality, while another offers comforting solace and beauty. One may embrace abstraction and ambiguity, while another creates detailed symbolism and specific meaning. Some artists explore the deep things of the soul and of spirituality, while others prefer the simplicity of everyday occurrences and interactions. Each are honoring the Creator’s spark in them in distinctive and inimitable ways.

The diversity of art from different periods, styles, and mediums allows us to consider the vast scope of human experience and, frequently, to dig a little deeper to understand and empathize. It will require more of you to understand a Buddhist mandala painting from Tibet or a conceptualist artwork of the twentieth century. In art, as in life, things that are outside your experience and from a different culture, religion, race, or century may initially seem strange, confusing, or even uninteresting to you. You might be inclined to reject these alternate and unfamiliar views of the world. If you approach these experiences with an open mind, in a spirit of learning, you may be surprised at all you can learn.

This does not mean that you will like all of these different types of art in the end. Truly, the world would be a much less interesting place if everyone had the same preferences and interests. But as you study these different types of art, your capacity for understanding differences will be expanded. As you research, you will learn that the Buddhist painting that seemed odd and incomprehensible is a tool for prayer and meditation, one that helps people focus as they pray and seek for enlightenment, inspiration, and transcendence. If you have ever struggled with prayer or found it hard to quiet your mind and listen, you suddenly have something in common with Buddhist monks and practitioners who have used mandala paintings to assist them.

Another truth that I have learned from the diversity of artwork in the world parallels perfectly with a gospel principle that I am still trying to learn: the beautiful and the terrible exist simultaneously everywhere. Both the artist who boldly calls for social change by showing the ugliness of the world and the one who captures the splendor and majesty around us are depicting important realities. Both are needed. We believe in an attentive God of miracles and a world of exquisite beauty, compassion, and goodness; we also believe in a God of agency and see a world of violence, terrorism, and unbelievable cruelty.

It is a comforting truth that God may manifest Himself powerfully in the small details of your life (helping you find lost keys or sending a friend at just the right moment) while being seemingly absent in the larger issues. As He allows agency and life’s circumstances to unfold, He does not resolve all conflict and difficulty. In these situations, He stands beside us and often, I believe, weeps with us as sorrow and hardships transpire in His imperfect, beloved world. The key is to not become myopic and see only what is right in front of you—just the beautiful or only the terrible—and draw narrow and often incorrect conclusions.13 It is a mark of spiritual maturity to be able to hold both of those truths in your heart at the same time. And it is tested faith that is able to weather these paradoxes, leaning upon the Lord’s pronouncement that His ways are not our ways and His thoughts not our thoughts (see Isaiah 55:8–9).

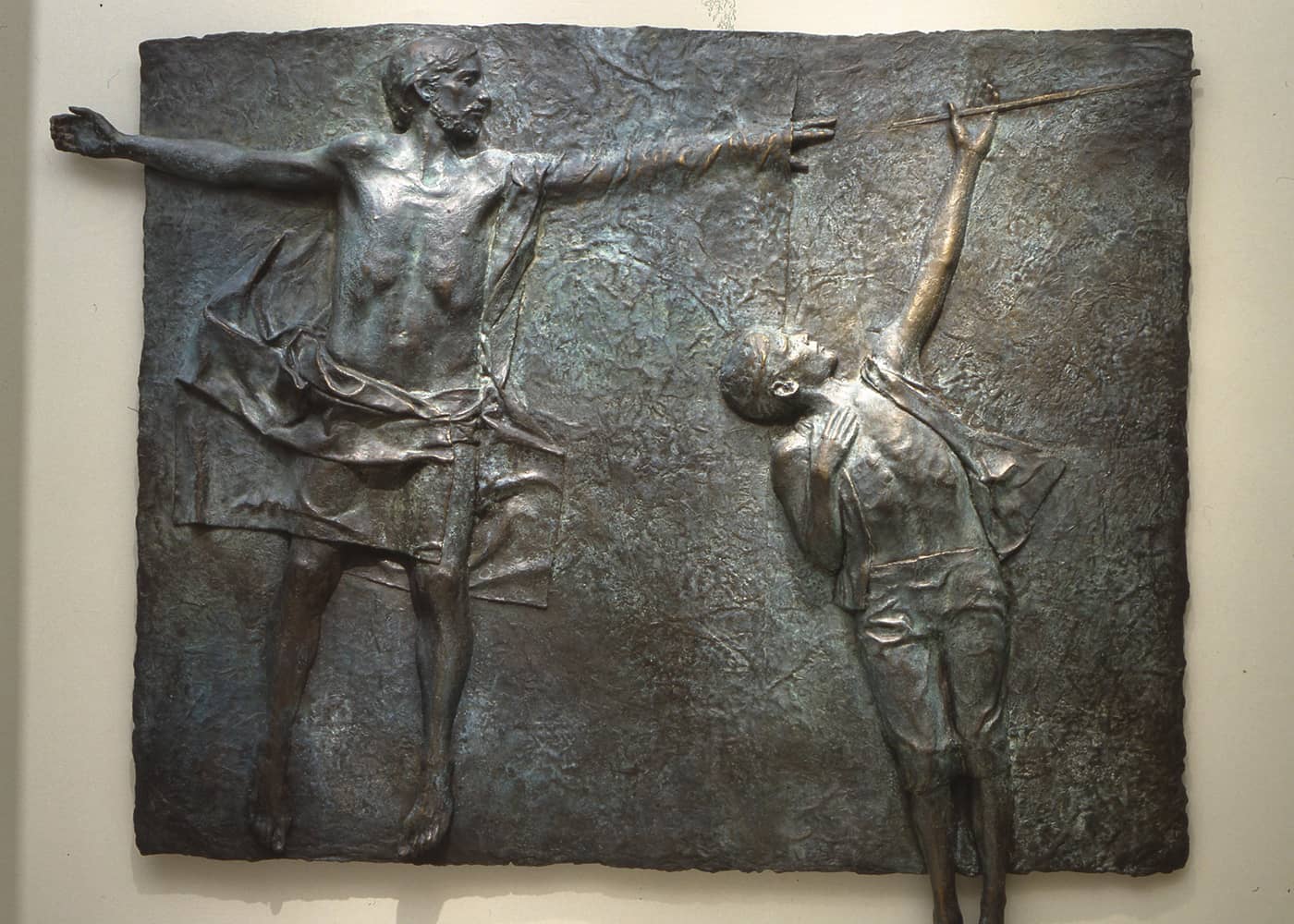

As each of us strives to find and develop the Creator’s spark within us, we must seek for divine assistance and personal revelation to guide our choices and direction. Finding this path and fostering a spiritually based life require daily dedication and commitment to quieting the noises of the world. It can sometimes feel like a dive into the unknown and a leap of faith. Artist Franz Johansen, a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who taught at BYU and passed away in 2018, gave us some visual insight into this idea with his The Rod and the Veil sculptural relief from 1975 in the Church History Museum. The young man who reaches for the rod stands for all of us, reaching for truth, for God’s word in our life, for guidance, for faith. Unlike many depictions of the rod leading to the tree of life, this rod isn’t waist-high, at walking level; it requires reaching and stretching. Because of this earthly veil, this “glass, darkly,” the young man cannot see that behind him he has divine assistance. The Savior, arms stretched to remind us of His ultimate sacrifice, reaches out once again ready to offer His assistance if needed.

I love Johansen’s version of this; it reminds us that we may not see the holy help around us, but it is there. I believe that the Savior stands behind to assist as we stretch to reach our potential and weeps with us when we struggle.

These are just a few examples of how art and the gospel have transformed my thinking, cultivated my empathy for others, and comforted my soul. In whatever field you are pursuing, from engineering to medicine, law to history, you will need these abilities and you will need to be creative. Those who succeed must be able to think outside the box, consider unfamiliar avenues, and explore new possibilities. Thomas Edison is quoted as saying, “Inventors must be poets so that they may have imagination.”14 The underlying idea here is that by channeling creativity, even in a very different field than your chosen vocation, you will be able to call upon that creative ability in other ways as well.

Foster this creativity in your everyday life. Consider your interests and find a way to pursue them. There is a season for all things in life, so now you may have limited time. But even with limited time, you can visit a museum, mold some clay, make a drawing, or write a poem. Prioritize this part of your life as you move forward. Sign up for that dance class, learn the instrument that you always imagined playing, experiment with those watercolor pencils, organize a colorful garden, or design something. The joy that this creativity generates is part of the outcome, but there is also a transformative power that happens as we create: we learn in small but meaningful increments about the creative process and become more like our Creator.

It is my prayer that we might be true to the Creator’s spark that is in each of us and use that spark to make our corner of the world a better place. We are all profoundly needed in this journey; your gift might be just what your family, your ward, your neighborhood, and the world are lacking. I hope that each of you feel deeply loved and essential in the family of God. As we hold on to our faith, He will transform our hearts and our perspectives so that they will beat in harmony with His heart and the hearts of our fellowmen. That we might do so is my prayer. In the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

NOTES

1. Anna Klumpke, Rosa Bonheur: The Artist’s (Auto)biography, trans. Gretchen van Slyke (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 220–21.

2. Kevin J Worthen, “Persevere in Unity,” BYU devotional address, 12 January 2021.

3. Elie Wiesel, Night, trans. Marion Wiesel (New York: Hill and Wang, 2006), 34.

4. Wiesel, Night, 65.

5. Elie Wiesel, in “Elie Wiesel: The Tragedy of the Believer,” interview with Krista Tippett, 20 November 2003, On Being (Speaking of Faith), podcast, onbeing.org/programs/elie-wiesel-the-tragedy-of-the-believer.

6. Emily Dickinson, poem no. 193, in The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, ed. Thomas H. Johnson (New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 1960), 91.

7. See also L. Todd Budge’s recent talk, “‘Broke’ Hearts and Contrite Spirits,” BYU devotional address, 2 February 2021.

8. Christian writer and Duke divinity professor Kate Bowler explores this idea more thoroughly in Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved (New York: Random House, 2018).

9. Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 1960), 39.

10. “Panel and Line Locations on the Wall,” The Moving Wall, 21 April 2013, themovingwall.org/docs/wallmaps.htm; quoted in Erin Blakemore, “This 21-Year-Old College Student Designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial,” History Stories, History, 13 September 2017, updated 22 February 2019, history.com/news/the-21-year-old-college-student-who-designed-the-vietnam-memorial. See also Phil McCombs, “Maya Lin and the Great Call of China,” Lifestyle, Washington Post, 3 January 1982, washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1982/01/03/maya-lin-and-the-great-call-of-china/544d8f2b-43b4-45ec-989b-72b2f2865eb4.

11. Antonio Cassese, quoted in Lawrence Weschler, Vermeer in Bosnia: Selected Writings (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 14.

12. Weschler, Vermeer in Bosnia, 14; emphasis in original.

13. See Russell M. Nelson, “Let God Prevail,” Ensign, November 2020.

14. Thomas Edison, letter to Edward N. Hurley, 12 January 1918, Henry Ford Museum Library; quoted in Matthew Josephson, Edison: A Biography (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1959), 463. See also Blaine McCormick, in “Thomas Edison: Inventor and Poet,” interview with Neal Conan, Talk of the Nation, NPR News, 13 August 2007, npr.org/transcripts/12741251.

ARTWORK REFERENCED

In Order of Mention

Rosa Bonheur (1822–99), The Horse Fair, 1852–55, oil on canvas, 96 1/4 x 199 1/2 inches, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Cornelius Vanderbilt, 1887.

Arnold Friberg (1913–2010), Peace, Be Still, oil on canvas, 33 x 57 inches, Brigham Young University Museum of Art, gift of Roy and Carol Christensen. © Creative Fine Art Inc.

Maya Lin (b. 1959), Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington, DC, 1982, National Park Service.

Dorothea Lange (1895–1965), Migrant Mother, (Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California), 1936, 4 x 5 inches, photograph, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives.

Maynard Dixon (1875–1946), Forgotten Man, 1934, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 1/8 inches, Brigham Young University Museum of Art, 1937.

Johannes Vermeer (1632–75), View of Delft, c. 1660–61, oil on canvas, 96.5 x 115.7 centimeters, Mauritshuis, The Hague.

Johannes Vermeer (1632–75), Girl with a Pearl Earring, c. 1665, oil on canvas, 44.5 x 39 centimeters, Mauritshuis, The Hague.

Johannes Vermeer (1632–75), Milkmaid, c. 1660, oil on canvas, 45.5 x 41 centimeters, Rijksmuseum, purchased with the support of the Vereniging Rembrandt purchase in 1908.

Johannes Vermeer (1632–75), Woman Reading a Letter, c. 1663, oil on canvas, 46.5 x 39 centimeters, Rijksmuseum, on loan from the city of Amsterdam (A. van der Hoop Bequest in 1885).

Johannes Vermeer (1632–75), Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, c. 1662, oil on canvas, 45.7 x 40.6 centimeters, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Marquand Collection, gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1889.

Patrick Dougherty (b. 1945), Windswept, 2018, installation of willow saplings, Brigham Young University Museum of Art.

Gabriel Dawe (b. 1973), Plexus no. 29, 2014, Gütermann sewing thread, hooks, painted wood, Brigham Young University Museum of Art installation.

Franz Johansen (1928–2018), The Rod and the Veil, 1975, sculptural relief, Church History Museum, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Janalee Emmer, associate director at the BYU Museum of Art, delivered this devotional address on March 9, 2021.