Clearly, therefore, BYU parallels, but is not in, the secular stream of American universities; it is instead a unique tributary to mankind that springs from the fountain of the gospel.

If Brigham Young University did only that which other universities do, and in the same way, there would be little reason for the Church to operate it. The traditional roles a university plays—such as transmitting accumulated knowledge from generation to generation, discovering new knowledge through research, and providing various forms of service to mankind—should be and are much in evidence at BYU. BYU must continue to do these things well enough to meet the reasonable standards of the academic world, for as Brigham Young urged, “We should be a people of profound learning pertaining to the things of the world”¹ but without being tainted by “pernicious, atheistic influences.”²

But BYU must do even more: it must also meet the higher standards of the kingdom of God. Clearly, therefore, BYU parallels but is not in the secular stream of American universities; it is instead a unique tributary to mankind that springs from the fountain of the gospel. This paralleling separateness is important to maintain, not only for the Church’s sake but for the sake of society as well, for to imitate the world indiscriminately is not to provide needed leaven for the world.

Originally, occidental universities were tied to religious purposes, and a modern expression of linkage between academia and correct theology is clearly needed. The secularization of so many universities in recent decades has often added to the malaise and loss of purpose that seem to seep through to the marrow of some of these institutions. There is a growing, informal alliance between many educationalists and existentialists, and some counterforce to that tacit alliance is clearly called for.

BYU can provide such counterpoint, because at the Y there is concern over conduct as well as curriculum, concern for developing character in students as well as their competency. How appropriate this is, since so much recent human misery has resulted from flaws in character and not failures in technology! Further, since students learn so much from each other, the selection of peers is as significant an act as the selection of professors. Thus, in important ways, the human environment at BYU is deliberately different, and self-selection by faculty as well as students who desire such a campus is constantly in evidence.

It is important that there be some pluralism in higher education. The essence of freedom is choice, and choice requires options. It was John Stuart Mill, in his essay “On Liberty,” who noted the practical advantages of pluralism in which individuality is a helpful factor:

The unlikeness of one person to another is generally the first thing which draws the attention of either to the imperfection of his own type, and the superiority of another, or the possibility, by combining the advances of both, of producing something better than either.³

The individuality of institutions has corresponding advantages too.

As BYU enters a new era with such uniqueness and with rising academic quality, it is now in a position to turn its face outward to the world without having to explain itself too self-consciously.

In the words of Ezekiel, BYU is in a position to show “the difference between the holy and profane”⁴ in the realm of education, and under the able leadership of President Dallin H. Oaks and highly competent colleagues at all levels, it is meeting its rendezvous with destiny.

BYU’s uniqueness has helped it to avoid some of the major problems of other universities in recent years. For instance, there began in American higher education several decades ago a great academic apostasy from advisement, in which faculties in many universities gave up—quickly and gladly—the role of advisers to students and sought to institutionalize this service in counseling centers. While the latter may be needed, they are not a substitute for what so many students often seek: proximity to professors.

Neither was there the student disenchantment at BYU that occurred on some other campuses in the sixties. This campus is a place where the doctrine of in loco parentis is alive and well.

There was no real crisis of purpose at BYU. Neither did BYU suffer from loss of support by alumni, nor was there a gap between the governing board and the BYU faculty—two harsh consequences that emerged elsewhere. The uniqueness of this university will also help it in the future to ride out difficulties that may prove traumatic for some other institutions.

The educational chemistry on BYU’s campus, therefore, involves a committed, competent faculty; a committed, competent staff; a committed, competent administration; a special student body; and, certainly, a special governing board. These groups are united on basic values and purposes—an academic adhesive that holds fast under pressure. The blend of these things permits BYU to do uncommon things that cannot be done as easily or as well elsewhere. As the university gains momentum, those who will teach, study, and serve there (in BYU’s second century) will both experience and help to preserve this special educational environment.

By being unique in some respects, BYU will make a contribution not only to the kingdom but to all of mankind, including in its resistance to the educational fashions and fads of the time, when those trends are inimical to the interests of mankind.

There is a reported historical parallel involving Admiral Robert E. Peary, who was trying to reach the North Pole years ago. After determining his position, he drove his dog team northward, only to be disappointed by learning later that he was miles farther south than he had been earlier. It became clear that he was northbound on a giant ice floe that was resolutely and rapidly drifting southward. So it is with so many of mankind’s sincere secular efforts today. Men can be anxiously engaged but without being engaged in good causes.⁵ If men are not steering by absolute truth, they will drift in the rolling sea of relativism.

The attack on human problems by sincere, scurrying, secular soldiers is sometimes gallant but seldom effective. It is much as Marshall Pierre Bosquet said of the charge of the Light Brigade: “It is magnificent, but it is not war.”⁶ We can send generations of students forth to do battle in the war on poverty, but these battles will be finally won only on the basis of eternal principles—which make possible real solutions, not simply cosmetic applications of anxiety.

The increasingly rigorous academic program at BYU requires and receives the support of the ecclesiastical leaders of the many student stakes there. Church recreational and social activities, for instance, must not be so time consuming that they become a substitute for the improvement of a student’s ability to write well.

To communicate, we must speak to men after the manner of their understanding.⁷ In the world of scholarship, the language—but not the jargon—of scholarship needs to be used, and BYU will increasingly reach out to the scholarly world with relevant research growing from the principles of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Just as the Church in pioneer times benefited by the counsel and friendship of a nonmember friend, Colonel Thomas L. Kane, so BYU can make friends with the “Colonel Kanes” of the world of letters and intellect—with fine men and women of talent and integrity who may not subscribe fully to the belief system of the kingdom of God but who share many of our values and concerns.

Significantly, in a letter to President Brigham Young on December 4, 1873, Colonel Kane urged the Church to establish its own university rather than have the Church be entirely dependent on sending its youth “abroad to lay the basis of the opinions of their lives on the crumbling foundations of modern unfaith and specialism.”⁸ These individuals are often very perceptive in their own diagnoses of the ills that beset the world. There are conceptual coalitions to be formed; there are clear statements that need to be made about human nature and human behavior; there are insights to be shared and warnings to be given.

The sea breeze of the scriptures must be played on the fevered brow of mankind today if that fever is to be broken. The Church and, therefore, BYU are entering together an era when the “ensign to the nations,”⁹ the “light unto the Gentiles,”¹⁰ will shine forth, and this illumination can be increased by the incandescence of orthodox scholars who can help to illuminate and to warm the path. Men and women are coming—and will come—from many lands to Zion, including to Zion’s university, to ask (in different voices) to be shown the Lord’s way.

Since so much of what a university is about involves truth and knowledge, a Christian university would need to pay heed to what Christ has said about those two topics. The Savior said “the key of knowledge” is “the fullness of the scriptures.”¹¹ Little wonder that a Church possessed of added scriptures would hear its prophets indicate that being “about [our] Father’s business”¹² includes education, especially when that education provides man with his moral foundation so that he can make his way in the world without being overcome by the world. We need not be fearful of facts; nothing lasting will come out of the territory of truth (or appear suddenly on the frontier of fact) that cannot be incorporated with the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Most students are naturally believing of the gospel. They are like a young bird who teeters briefly on the edge of the nest (refusing to be agnostic about the law of aerodynamics), then flutters, and finally soars! Purpose-filled and believing students who get wise experience in the management of their time and talents—which is really the management of self—will be sought by a society eager for competent idealists with integrity and industry.

Students in a proper peer group can do so much to help one another learn, including the development of those social skills upon which the governance and maintenance of a free society truly depend, to say nothing of the effectiveness an individual needs in family life.

Thus, BYU can both help to motivate students to want to serve mankind and also provide them with the skills to do so. By understanding the implications of gospel truths, students can be clearheaded about how to work toward desirable change on this planet while simultaneously learning the importance of succeeding in their own families rather than simply charging off quixotically to tilt against windmills while their family perishes at home. Prospective mothers, for instance, deserve the best possible education. As Dr. Charles D. McIver once observed: “When you educate a man, you educate an individual; when you educate a woman, you educate a whole family.”¹³

One important caveat: as the Church grows and becomes more and more global, a smaller and smaller percentage of all Latter-day Saint college-age students will attend BYU or BYU–Hawaii campus (a four-year college) or Ricks (a two-year college) or LDS Business College, each of which is making its own unique contribution to society and the Church, though the latter three institutions are not treated herein. Latter-day Saint students attending other colleges and universities in the United States and around the world number over 100,000, and of these, about 70,000 are attending one of our nearly 500 institutes of religion or are using the self-instruction institute course. Thus, while attending BYU can be a very special experience for its students, that is not the educational route the vast majority of Latter-day Saints will travel. This puts an even greater follow-through responsibility on those who do enroll at BYU.

BYU can, and will, build some academic peaks of unquestionable excellence; several of these are emerging even now. BYU will simultaneously continue to maintain a special environment that permits people to experience how individuals can live together in love and truth and learn through self-reliance to govern themselves by correct principles. Those who have had such an experience will never be satisfied later on with anything less!

The convergent implementation of so many correct principles in the educational enterprise at BYU is not perfectly done; it is, nevertheless, impressively done.

It was said of Rome at her apogee that men did not love Rome because she was great but that Rome was great because men loved her. BYU will earn academic esteem, but the respect and love of the Lord’s university by the members of the Church will be a crucial ingredient in the process of BYU’s achievement of greatness in its second century!

© by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Notes

1. Brigham Young, “Remarks,” Deseret News Weekly, 6 June 1860, 97.

2. Brigham Young, letter to his son Alfales Young, 20 October 1875.

3. John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (London: John W. Parker and Son, 1859), chapter 3, p. 128.

4. Ezekiel 44:23.

5. See Doctrine and Covenants 58:27.

6. Pierre Bosquet, quoted in Familiar Short Sayings of Great Men, comp. Samuel Arthur Bent (Boston: Ticknor and Company, 1887), 68.

7. See 2 Nephi 31:3; Doctrine and Covenants 1:24.

8. Thomas L. Kane, letter to Brigham Young, 4 December 1873, 8; in box 40, folder 14, Thomas L. Kane, 1869–1873, Letters from Church Leaders and Others, 1840–1877, Brigham Young Office Files, 1832–1878 (bulk 1844–1877), Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

9. Isaiah 5:26; 2 Nephi 15:26.

10. Doctrine and Covenants 86:11.

11. Joseph Smith Translation, Luke 11:53.

12. Luke 2:49.

13. Dr. Charles D. McIver is often credited with this saying. For an earlier published iteration, see Catherine E. Beecher, A Treatise on Domestic Economy: For the Use of Young Ladies at Home, and at School, rev. ed. (Boston: Thomas H. Webb and Company, 1843), 37: “The proper education of a man decides the welfare of an individual; but educate a woman, and the interests of a whole family are secured.”

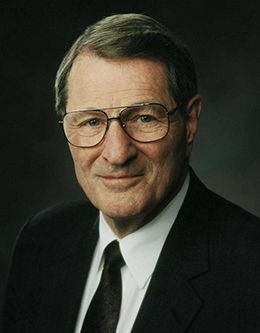

Neal A. Maxwell, serving as commissioner of the Church Educational System during BYU’s centennial year, wrote this article that was published in the October 1975 issue of the Ensign, 6–9.