When we in the “household of faith” have paid the price of excellence in our preparation and in our individual efforts, when we have become thoroughly schooled in the gospel, when we have qualified by worthiness and spirituality, and when we are seeking for his guidance continually, as he chooses to speak, and are fully qualified to press on with demonstrable excellence when he leaves us to our own best judgment, we will be making the progress we must make in order to become “the fully anointed university of the Lord.”

My dear fellow workers:

The theme of this annual university conference—“A House of Learning, a House of Faith”—comes from the 88th section of the Doctrine and Covenants.1 Since I have felt impressed to devote this annual president’s message to a spiritual subject, I will focus on the second half of that theme, pointing to the ideal of Brigham Young University as “a house of faith.”

In his second-century address, delivered on this campus two years ago, President Spencer W. Kimball helped us see Brigham Young University, present and future, through the eyes of a living prophet. He saw the need and challenged us to increase effort and accomplishment in our various responsibilities. He saw the need and exhorted us to greater spirituality and worthiness in our individual lives. Then, with prophetic insight, he concluded with this promise, which identifies our goal and reminds us that we have not yet arrived: “Then, in the process of time, this will become the fully anointed university of the Lord about which so much has been spoken in the past.”2

How are we to achieve that prophetic destiny as “the fully anointed university of the Lord”? (1) We must understand the university’s role in the kingdom of God; (2) we must be worthy in our individual lives; (3) we must be fearless in proclaiming the truths of the gospel of Jesus Christ; (4) we must be exemplary in efforts understandable to the world; and (5) we must seek and heed the inspiration of God in the performance of our individual responsibilities. I will discuss each of these requirements in that order.

I. The University in the Kingdom

The first and greatest revelation of this dispensation on the subject of education was the 88th section of the Doctrine and Covenants, given in December 1832 and January 1833. The Lord directed the Saints to build a temple in Kirtland:

Organize yourselves; prepare every needful thing; and establish a house, even a house of prayer, a house of fasting, a house of faith, a house of learning, a house of glory, a house of order, a house of God.3

This revelation also directed the Saints to begin a School of the Prophets. This school, which Joseph Smith promptly established in Kirtland in the winter of 1833, more than three years before the dedication of the temple, was the forerunner of all educational efforts in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The 88th section of the Doctrine and Covenants, which defined the objectives of the School of the Prophets and gave related commandments, counsel, and knowledge, is still the basic constitution of Church education. It defines Brigham Young University’s role in the kingdom.

The immediate purpose of the School of the Prophets was to train the restored Church’s earliest leaders for the ministry, especially for missionary work. The Church’s first educational effort was also intimately related to the teachings to be communicated in the temple. The school was intended to be housed in the temple.4

The commandments and knowledge communicated in the 88th section concern the temple, the school, and the work of the ministry as an inseparable and unified whole. That is their eternal relationship. The laws and conventions and shortsightedness of man currently compel us to separate these activities for some purposes, but to a Father in Heaven who has given no temporal law and to whom all things are spiritual,5 the work of temple, school, and ministry must all be seen as the unified work of the kingdom.

Often in the last three years I have stood at the window of my office looking out across the northern part of the campus to the Language Training Mission and the temple. I tell the visitors who share this sight that these three institutions—university, mission, and temple—are the most powerful combination of institutions on the face of the earth. They make this place unique in all the world. Now, after studying the 88th section, I see even more clearly the common origins of all three institutions in a single great revelation. I am grateful that it has been during the period of our service that the servants of the Lord have united in one sacred location the Lord’s university, the Lord’s temple, and the school where His missionaries “become acquainted with . . . languages, tongues, and people.”6

We are all familiar with the comprehensive curriculum the Lord outlined in section 88. He directed these early Saints to “teach one another the doctrine of the kingdom”7 and “the law of the gospel.”8 Beyond that, He commanded them to teach “all things that pertain unto the kingdom of God.”9 They must “diligently . . . [seek] words of wisdom . . . out of the best books.”10 They should be instructed in

things both in heaven and in the earth, and under the earth; things which have been, things which are, things which must shortly come to pass; things which are at home, things which are abroad; the wars and the perplexities of the nations, and the judgments which are on the land; and a knowledge also of countries and of kingdoms.11

Two months after the school commenced, the Lord reinforced this breadth of instruction by commanding the Prophet to “study and learn, and become acquainted with all good books, and with languages, tongues, and people.”12

The Lord also revealed that the technique of learning was to reach beyond the conventional pedagogy of that day (or this). Those who studied in the School of the Prophets were to “seek learning, even by study and also by faith.”13

All these verses from the 88th section are familiar and have often been used to stress the universal concern of our inquiries at Brigham Young University, comprehending the secular as well as the spiritual, and of our special approach to learning, comprehending conventional study and the acquisition of insights from the Spirit through faith. But this great revealed charter of the Church Educational System contains much more.

At the beginning of the 88th section, the Lord instructed His little flock in the most fundamental principle of all learning: All things were made by the power and glory of God and His Son, Jesus Christ.14 He is the source of the light of the sun and of the light that quickens our understandings.15 It is through Jesus Christ that we receive “the light which is in all things, which giveth life to all things, which is the law by which all things are governed, even the power of God . . . who is in the midst of all things.”16

What could be more basic to a learning effort than this knowledge that God is the power by which all things were made and governed and that He is in all things, comprehends all things, and is the source of all enlightenment?

This revelation also declares the purpose of learning in the Church Educational System. It is that we “may be prepared in all things” when the Lord shall send us to magnify the calling whereunto He has called us and the mission with which He has commissioned us.17 In other words, we receive enlightenment as stewards with a duty to use that knowledge to go out into the world to warn and bless the lives of the Gentiles18 and “to prepare the saints for the hour of judgment which is to come.”19

The attitude that should motivate all our efforts in education is specified in the 67th verse of section 88: our eye should be single to the glory of God. That short verse also contains the most significant promise ever given pertaining to education:

And if your eye be single to my glory, your whole bodies shall be filled with light, and there shall be no darkness in you; and that body which is filled with light comprehendeth all things.

In other words, those who achieve singleness of purpose in love of God and service in His kingdom are promised that they will ultimately comprehend all things. The manner of learning that would fulfill this unique promise was revealed to the Prophet Joseph Smith six years later in Liberty Jail:

God shall give unto you knowledge by his Holy Spirit, yea, by the unspeakable gift of the Holy Ghost, that has not been revealed since the world was until now.20

One of the most distinctive characteristics of Brigham Young University in this day is our proud affirmation that character is more important than learning. We are preoccupied with behavior and consider personal worthiness to be an essential ingredient of our educational enterprise. That educational philosophy was revealed by God. Again and again the 88th section stresses the importance of worthiness for teacher and student.

The Lord commanded:

Prepare yourselves, and sanctify yourselves; yea, purify your hearts, and cleanse your hands and your feet before me, that I may make you clean.21

Therefore, cease from all your light speeches, from all laughter, from all your lustful desires, from all your pride and light-mindedness, and from all your wicked doings.22

Again:

Abide ye in the liberty wherewith ye are made free; entangle not yourselves in sin, but let your hands be clean, until the Lord comes.23

Another verse of commandment concludes with a promise that ties the purifying effort directly to the process and objective of learning:

Cease to be idle; cease to be unclean; cease to find fault one with another; cease to sleep longer than is needful; retire to thy bed early, that ye may not be weary; arise early, that your bodies and your minds may be invigorated.24

Soon after the beginning of the School of the Prophets and as a direct result of experiences in the meetings of the school, the Lord gave Joseph Smith the revelation designated as “a Word of Wisdom.”25 This was also a commandment with a promise. Those who observed its proscriptions, “walking in obedience to the commandments, shall receive health in their navel and marrow to their bones,”26 “shall run and not be weary, and shall walk and not faint,”27 and “the destroying angel shall pass by them, as the children of Israel, and not slay them.”28 But the promised spiritual blessings were of at least equal importance, especially for those involved in learning:

And all saints who remember to keep and do these sayings, walking in obedience to the commandments, . . .

. . . shall find wisdom and great treasures of knowledge, even hidden treasures.29

The teacher in the School of the Prophets was commanded to be worthy, prepared, reverent, and exemplary in conduct. The Lord commanded that the teacher “should be first in the house . . . , that he may be an example.”30 He should also “offer himself in prayer upon his knees before God, in token or remembrance of the everlasting covenant.”31

The students must also be worthy. When a student entered the School of the Prophets, the teacher was commanded to salute him “in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, in token or remembrance of the everlasting covenant,” in fellowship, and in a determination to be a friend and brother and “to walk in all the commandments of God blameless, in thanksgiving, for ever and ever.”32 If students were unworthy of this salutation and of the covenant, the Lord commanded that they “shall not have place among you.”33

Finally, the Lord made a promise in the 88th section to all who would participate in the important educational work of His kingdom. This promise applies to efforts in our day just as it did then:

Draw near unto me and I will draw near unto you; seek me diligently and ye shall find me; ask, and ye shall receive; knock, and it shall be opened unto you.

Whatsoever ye ask the Father in my name it shall be given unto you.34

The acquisition of knowledge is a sacred activity, pleasing to the Lord and favored of Him. That fact accounts for what President Kimball called “the special financial outpouring that supports this university.”35 “The glory of God is intelligence, or, in other words, light and truth.”36 The holiest places on earth—the temples of God—are places of instruction. From the beginning of this dispensation the Lord has associated the temple, the school, and the ministry—a trio now brought together in this spot.

Under the direction of the servants of the Lord, Brigham Young University’s role is to be a house of faith, a sanctified and fully effective participant in the revealing and teaching and reforming mission of the kingdom of God. When we can perform this university’s calling in a manner fully acceptable to the Lord and His servants, we will become what President Kimball has called “the fully anointed university of the Lord.”

II. Worthiness

If we are to achieve that prophetic destiny, we must follow the general charter of Church education as revealed in the Doctrine and Covenants and the more recent and more specific direction of the living prophets. Each of these authorities has told us that our first challenge is to be worthy in our personal lives.

In the 88th section the Lord commanded His educators to be pure, worthy, prayerful, and exemplary in all things. In his great address to BYU faculty and staff a decade ago, “Education for Eternity,” President—then Elder—Kimball declared: “BYU is dedicated to the building of character and faith, for character is higher than intellect, and its teachers must in all propriety so dedicate themselves.”37 More recently, President Kimball explained that we cannot make the progress needed at BYU

except we continue . . . to be concerned about the spiritual qualities and abilities of those who teach here. In the book of Mosiah we read, “Trust no one to be your teacher nor your minister, except he be a man of God, walking in his ways and keeping his commandments.” . . .

We must be concerned with the spiritual worthiness, as well as the academic and professional competency, of all those who come here to teach.38

One of the conditions of employment at Brigham Young University is observance of all the principles of our code of honor. We cannot expect less of ourselves than we expect of our students.

Each worker in this university—and especially those who are in teaching positions, formal or informal—must be role models for the young people who study here. Individuals whose personal life cannot meet that high standard of example are honor bound to repent speedily, seeking the help of their bishop and/or their university supervisor as the circumstances warrant, or to obtain other employment.39

Our annual interviews with all university personnel seek to encourage and assure that worthiness. They must be carried out faithfully by both parties.

I am always humiliated when a bishop or stake president contacts me or another university official to say that there is a BYU teacher or administrator or staff member in his ward or stake who refuses to take Church assignments, is not faithful in attending Church meetings, or does not pay a full tithing.

The payment of an honest tithing is an expectation of employment at Brigham Young University. How could it be otherwise, when about two-thirds of the university’s budget comes from appropriations from the tithes of the Church? These sums are paid in a freewill offering by members of the Church throughout the world, often at great sacrifice. Many of these members have standards of living and incomes far below what is enjoyed by the employees of this university.40

The Church holds us up as examples of faithful Latter-day Saints whose lives are worthy of emulation. If leaders or members of our wards know that we are not worthy, our continued employment at BYU is a trial to the faith of those who know us, an insult to the standards of this institution, and an affront to the Church. None of us can afford to be in that position. While we do not expect perfection, we do expect that all our BYU personnel will observe all the principles of our code of honor and that all of us who are members of the Church will be worthy of a temple recommend and will be conscientiously working to preserve and improve our spirituality. We expect the same high standards of personal worthiness of our workers who are not members of our Church, except that they are not expected to pay tithing and they have no responsibility of attendance or activity in our Church.

Workers at BYU are also expected to be worthy examples of Christian living in the performance of all their duties at the university. From time to time we are grieved to receive evidence of dishonesty by BYU employees, including instances in which persons have stolen the property or the time of the university. The theft of university time is far more common and just as deplorable as the theft of property. We are also grieved to hear reports of profanity or abusive language by BYU personnel. Foul language of any kind is deeply resented by students and others and has no place on the job at BYU. The same is true of untruthful reports, backbiting, evil speaking, and excessive displays of anger.

I am always saddened when I hear that supervisors or others at the university have “chewed out” a fellow worker in a degrading manner or have held someone up to public ridicule in the eyes of colleagues, students, or others. We must have high performance from our university workers, and when a person’s performance does not measure up to standards, he or she must be corrected, including, if necessary, being dismissed from a position or from university employment. All of this will be necessary, just as it is in other employment and, indeed, in Church positions. But we should be consistent with the examples of priesthood leadership, and correction and changes should be accomplished without anger, rancor, or public embarrassment.

We must be especially exemplary in our communications with persons who telephone us or come to the campus as guests. Let us strive to be Christlike in all our personal dealings, always showing gentleness, love, and consideration for all. Only by this means can we be worthy residents and teachers in the household of faith.

III. Testimony and Gospel Teaching

All who study, teach, or work in a house of faith should be fearless in proclaiming the truth of the gospel of Jesus Christ. By the power of the Holy Spirit we should testify of God the Father and His Son, Jesus Christ. That faith and testimony should be paramount in our lives and in our teachings.

We must be more explicit about our religious faith and our commitment to it. In doing so we will fill a demonstrated need. Pollster George Gallup recently observed that Americans are “spiritually hungry.”41 “Increasing numbers . . . are disillusioned with the secular world, have rejected rationalism and are turning to ‘the life of the spirit for guidance.’”42 Our students share that hunger, and we must see that they receive spiritual food.

When a student entered the School of the Prophets, the teacher was commanded to salute him in the name of the Lord as a token of their mutual determination to keep the commandments of God.43 To serve that same purpose, our teachers and others in a position of authority at BYU should find occasion to bear their testimonies to students and fellow workers, to express their faith, and to be explicit about the relevance of the gospel in their lives. These commitments and attitudes should be explicit in our teaching. President Kimball underlined the importance of that subject in these words:

I would expect that no member of the faculty or staff would continue in the employ of this institution if he or she did not have deep assurance of the divinity of the gospel of Christ, the truth of the Church, the correctness of the doctrines, and the destiny of the school.

. . . Every instructor knows before coming to this campus what the aims are and is committed to the furthering of those objectives.

If one cannot conscientiously accept the policies and program of the institution, there is no wrong in his moving to an environment that is compatible and friendly to his concepts.44

A teacher’s most important possession is his or her testimony of Jesus Christ. It is more important than the canons and theories of any professional field. We should say so to our students. Similarly, we ought not to present ourselves as teachers at Brigham Young University unless we are living so that we are entitled to the continuous companionship and guidance of the Holy Ghost. In my opinion, the Lord’s statement that “if ye receive not the Spirit ye shall not teach”45 has very literal application to the teaching activities of this university.

Our testimonies are important to our students and to our fellow workers as our most important common bond. We are privileged to use expressions of faith in our teaching and other associations. In public institutions teachers are less free.

Each teacher must decide how gospel values will be made explicit in his or her own teaching. Some subjects can be permeated with gospel truths and values. In other subjects, reference to the gospel is more difficult. But in every class in this university a teacher can at least begin the teaching effort by bearing testimony of God, by expressing love and support for His servants, and by explaining the importance of the gospel truths in his or her life. And it would always be desirable for a teacher at BYU to affirm publicly the great truth expressed by President Joseph Fielding Smith that “knowledge comes both by reason and by revelation.”46 As President Kimball explained:

It would not be expected that all of the faculty should be categorically teaching religion constantly in their classes, but it is proper that every professor and teacher in this institution would keep his subject matter bathed in the light and color of the restored gospel and have all his subject matter perfumed lightly with the spirit of the gospel. Always there would be an essence, and the student would feel the presence.

Every instructor should grasp the opportunity occasionally to bear formal testimony of the truth. Every student is entitled to know the attitude and feeling and spirit of his every teacher.47

This is the responsibility of our non–Latter-day Saint teachers as well, and many fulfill it admirably. We know of several instances in which non–Latter-day Saint BYU faculty members have been among our most effective practitioners and teachers of wholesome Christian values, surpassing some of their Latter-day Saint colleagues in showing how these principles can and should be pervasive in our teaching and associations at BYU.

In my remarks to the faculty two years ago, I suggested that in order to be effective at teaching secular subjects and at integrating gospel concepts, we must be “bilingual.” I urged that we had to “be fluent in the language of scholarship . . . in order to command the respect of [the secular world]” and that we also had to “speak the special language of our faith” to communicate our adherence to the gospel values that illuminate our learning efforts and justify our existence as a university.48 I was pleased when President Kimball used this same metaphor in his second-century address and that the idea of being “bilingual” and the phrases “language of scholarship” and “language of [faith]” are becoming a familiar part of our vocabulary.49 But much remains to be done before BYU has met this challenge with the needed array of solid achievements in public and private communications.

I now feel prompted to add another dimension. The challenge to be bilingual involves more than the ability to speak both languages. That is a terrestrial skill at best. To be bilingual in the celestial sense, we must use the appropriate combination of the language of scholarship and the language of faith to assure that what we communicate is the whole truth as completely as we perceive it with the full combination of our scholarly and spiritual senses. That is the culmination of being bilingual. That is what President Harold B. Lee meant when he said that one purpose of our Church schools was

to teach secular truth so effectively that students will be free from error, free from sin, free from darkness, free from traditions, vain philosophies, and the untried, unproven theories of science.50

If we are to communicate at the highest level of the bilingual, we must be thoroughly prepared in our individual disciplines and also deeply schooled in the gospel.

Last week a student wrote me to complain that we “are not using the teachings of the prophets . . . in our classrooms as we could.”51 He criticized our teaching, especially in one particular department, as having a lack of balance. He described the prototype of a professor who “has a PhD in his academic discipline and the equivalent of an eighth-grade education in the gospel.”52 Although this student did not apply that description to any particular teacher, I would like to consider it as a challenge to each of us. If any teacher at BYU has a doctorate in his or her discipline but only grade-school preparation in the gospel, that teacher needs some spiritual development. The reverse is also true: a doctorate-level knowledge of the gospel will not suffice if we are poorly prepared in our individual disciplines.

In this university we are free to seek the truth—a “knowledge of things as they are, and as they were, and as they are to come.”53 As President Kimball has observed, at BYU we have “real individual freedom. Freedom from worldly ideologies and concepts unshackles man far more than he knows. It is the truth that sets men free.”54 Each of us should pursue that truth by study and by faith. Each of us should increase our qualifications to communicate that truth by an inspired combination of the language of scholarship and the language of faith. And each of us should gain a doctorate-level knowledge of the gospel as well as of our individual disciplines.

IV. Excellence in Secular Terms

I have already said a great deal on this next topic, so I will add but little here.

In his second-century address, President Kimball also challenged us to excel in terms understandable to the world in our teaching, in our creative work, and in all our activities. “While you will do many things in the programs of this university that are done elsewhere,” he said, “these same things can and must be done better here than others do them.”55

We can measure up to that challenge only with solid individual effort. President Kimball declared:

We must do more than ask the Lord for excellence. Perspiration must precede inspiration; there must be effort before there is excellence. We must do more than pray for these outcomes at BYU, though we must surely pray. We must take thought. We must make effort. We must be patient. We must be professional. We must be spiritual.56

Thus, when President Kimball challenged us to excel at literacy and the teaching of English as a second language, he reminded us that our efforts must be “firmly headquartered in terms of unarguable competency as well as deep concern.”57

All this reminds us that we cannot expect to be instruments in advancing the truth in our individual disciplines merely through studying theology and living righteous lives. When the Lord sends us to spread the gospel in all parts of the world, He expects us to use modern technology in transportation and communication. He has revealed these for our use. But isn’t it significant that He revealed these scientific wonders through natural channels to persons who were pursuing learning by secular means and for secular purposes?

There have been inspired men and women in every discipline. The Lord expects us to learn what we can from what He has previously revealed. We do not begin by rejecting what we sometimes call “the learning of men.” The learning of men, when it is true, is inspired of God. We must put our own efforts into paying the price of learning, of degrees, and of all intermediate steps necessary to acquire depth in our individual disciplines and skills. Future revelation in a particular discipline or skill is most likely to come to one who has paid the price of learning all that has previously been revealed. A lawyer is not likely to be inspired with the key to the energy crisis, nor a physicist with new truths about the science of government.

V. Inspiration to Assist Us

While we must not begin by rejecting the learning of men, we must not be confined by it. We must not be so self-satisfied and so deep in our own disciplines that we cannot be open to the truths contained in the scriptures or the illumination communicated by the Spirit. Can we afford to gloss over the scriptures when the prophet has testified that they “contain the master concepts for mankind”?58 Can we afford to make no attempt to use inspiration when that is our designated access to the Source and Author of all truth? In his second-century address, President Kimball declared:

This university shares with other universities the hope and the labor involved in rolling back the frontiers of knowledge even further, but we also know that through the process of revelation there are yet “many great and important things” to be given to mankind that will have an intellectual and spiritual impact far beyond what mere men can imagine.59

In light of what the prophet has said, how can we at Brigham Young University do our part “in rolling back the frontiers of knowledge even further”? We will not achieve this goal by the casual use of gospel insights implied in the phrase “philosophies of man mingled with scripture.” If we limit ourselves to the wisdom of men, we will wind up like the Nephites who, boasting in their own strength, were destroyed because they were “left in their own strength.”60

If we are to qualify for the choicest blessings of God—if we are to become the household of faith described in the revelation—our ultimate loyalty must be to the Lord, not to our professional disciplines. Elder Neal A. Maxwell illustrated that principle with the metaphor of the passport: “The LDS scholar has his citizenship in the kingdom, but carries his passport into the professional world—not the other way around.”61 The Lord once rebuked the Prophet Joseph Smith for a violation of this principle of loyalty. He declared:

Behold, how oft you have transgressed the commandments and the laws of God, and have gone on in the persuasions of men.

For, behold, you should not have feared man more than God.62

How would we stand in a conflict between the wisdom of man and the inspiration of God? Do we go on “in the persuasions of men”? Do we fear man more than God? Do we have our citizenship in the professional world and teach or do other work at BYU by virtue of a passport? I suggest that question for prayerful consideration in all our professional work.

This question not only calls on us to identify our ultimate loyalty—which I think each of us would quickly affirm is to the Lord—but also calls on us to authenticate our commitment in a way that is evident in our day-to-day professional work. Consider the implications of President Kimball’s charge that “we must not merely ‘ape the world.’ We must do special things that would justify the special financial outpouring that supports this university.”63 He explained one implication of that principle as follows:

We must be willing to break with the educational establishment (not foolishly or cavalierly, but thoughtfully and for good reason) in order to find gospel ways to help mankind. Gospel methodology, concepts, and insights can help us to do what the world cannot do in its own frame of reference.64

Are we secure enough in our professional preparation and attainments and strong enough in our faith that we can, as President Kimball said, “break with the educational establishment . . . for good reason . . . in order to find gospel ways to help mankind”? Although we are beginning to see some brilliant examples of gospel approaches in secular subjects at BYU, many of us are not yet ready to be this bold and this creative. As more and more of us acquire superior professional preparation and unshakable faith, we will see our overall performance improve. And when it does, the results will be spectacular.

Our Father in Heaven has invited us to “cry unto him”65 over our crops and our flocks “that they may increase”66 and “that [we] may prosper in them.”67 He has also told us through His prophet, “Counsel with the Lord in all thy doings, and he will direct thee for good.”68 Our Father in Heaven will teach us and help us and magnify us if we will only place our faith in Him and seek the inspiration of His Spirit. In that great charter of learning, the 88th section, He said:

Draw near unto me and I will draw near unto you; . . . ask, and ye shall receive. . . .

Whatsoever ye ask the Father in my name it shall be given unto you.69

Only by this means, with the Lord’s help, sought and received, can we fulfill President John Taylor’s remarkable prophecy: “You will see the day that Zion will be as far ahead of the outside world in everything pertaining to learning of every kind as we are today in regard to religious matters.”70

If we qualify by professional excellence, by worthiness, by loyalty, and by spirituality, we can receive the inspiration of God in our professional work. “We expect the natural unfolding of knowledge to occur as a result of scholarship,” President Kimball observed, but then he made this significant promise: “There will always be that added dimension that the Lord can provide when we are qualified to receive and He chooses to speak.”71

The First Presidency illustrated this principle in a special message published only a month ago: “Members of the Church should be peers or superiors to any others in natural ability, extended training, plus the Holy Spirit, which should bring them light and truth.”72 As Latter-day Saints, we are therefore privileged to augment our individual creative efforts with the insights of the gospel and the guidance of the Spirit. But as Brigham Young University faculty and staff, we are responsible to do so.

If we are to become the fully anointed university of the Lord, we must make use of those gospel insights and values “in order to find gospel ways to help mankind.” We must have access to “that added dimension that the Lord can provide when we are qualified to receive and He chooses to speak.” We must make use of those gospel insights and values and those spiritual powers in our teaching, in the selection and development of our creative efforts, and in all our work at the university. I have had that experience in my work, others have enjoyed it also, and I know it is available for those who have not yet experienced it.

On one occasion the Prophet Joseph Smith described the spirit of revelation in this manner:

A person may profit by noticing the first intimation of the spirit of revelation; for instance, when you feel pure intelligence flowing into you, it may give you sudden strokes of ideas, . . . and thus by learning the Spirit of God and understanding it, you may grow into the principle of revelation.73

On a choice occasion early in my service at BYU, when we faced an important and far-reaching decision on our academic calendar, I experienced that kind of revelation as pure intelligence was thrust upon my consciousness. I treasure that experience. It stands as a vivid testimony of the fact that when the matter is of great importance to His children and to His kingdom, our Father in Heaven will assist us when we are qualified and seeking.

At other times, I have felt the promptings of the Spirit to stay my hand from a course of action that was not in the best interest of the university. I was prevented from signing a legal document on one occasion and a letter on another. In each instance we reexamined the proposed action and within a few weeks could see, with the benefit of additional information not available to us earlier, that the restraining hand of the Spirit had saved us from an irreversible error. On another occasion I was prompted to accept a speaking appointment I would normally have declined, and the fulfillment of that assignment turned out to be one of the most significant public acts of my period of service and has led to many other important invitations, publications, and influences. At other times, in connection with my scholarly work on law and legal history, I have been restrained from publishing something that later turned out to be incorrect, and I have been impressed to look in obscure places where I found information vital to guide me to accurate conclusions on matters of moment in my work.

In all of this, I have been blessed beyond my own powers and have received an inkling of what the Lord can do for us if we qualify and reach out for His help in the righteous cause in which we are engaged.

When we in the household of faith have paid the price of excellence in our preparation and in our individual efforts, when we have become thoroughly schooled in the gospel, when we have qualified ourselves by worthiness and spirituality, and when we are seeking for His guidance continually, as He chooses to speak, and are fully qualified to press on with demonstrable excellence when He leaves us to our own best judgment, we will be making the progress we must make in order to become the fully anointed university of the Lord. Let us reach upward for this higher plane, and let us do so proudly, confidently, and speedily, taking heart in the question and promise of the apostle: “If God be for us, who can be against us?”74 May God help us to do what I believe He would have us do is my prayer, in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

© by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Notes

1. See Doctrine and Covenants 88:119.

2. Spencer W. Kimball, “The Second Century of Brigham Young University,” BYU devotional address, 10 October 1975.

3. Doctrine and Covenants 88:119.

4. See Doctrine and Covenants 95:17.

5. See Doctrine and Covenants 29:34.

6. Doctrine and Covenants 90:15.

7. Doctrine and Covenants 88:77.

8. Doctrine and Covenants 88:78.

9. Doctrine and Covenants 88:78.

10. Doctrine and Covenants 88:118.

11. Doctrine and Covenants 88:79.

12. Doctrine and Covenants 90:15.

13. Doctrine and Covenants 88:118.

14. See Doctrine and Covenants 88:5, 7–10.

15. See Doctrine and Covenants 88:7, 11.

16. Doctrine and Covenants 88:13.

17. Doctrine and Covenants 88:80.

18. See Doctrine and Covenants 88:81.

19. Doctrine and Covenants 88:84.

20. Doctrine and Covenants 121:26.

21. Doctrine and Covenants 88:74.

22. Doctrine and Covenants 88:121.

23. Doctrine and Covenants 88:86.

24. Doctrine and Covenants 88:124; emphasis added.

25. Doctrine and Covenants 89:1; see also Doctrine and Covenants 89.

26. Doctrine and Covenants 89:18.

27. Doctrine and Covenants 89:20.

28. Doctrine and Covenants 89:21.

29. Doctrine and Covenants 89:18–19.

30. Doctrine and Covenants 88:130.

31. Doctrine and Covenants 88:131.

32. Doctrine and Covenants 88:133.

33. Doctrine and Covenants 88:134.

34. Doctrine and Covenants 88:63–64.

35. Kimball, “Second Century.”

36. Doctrine and Covenants 93:36.

37. Spencer W. Kimball, “Education for Eternity,” address to BYU faculty and staff, 12 September 1967.

38. Kimball, “Second Century”; quoting Mosiah 23:14.

39. Dallin H. Oaks, “Annual Report on the University,” The Second Century: On with the Task, 1976 BYU annual university conference speeches, 24 (24 August 1976).

40. Oaks, “Annual Report,” 25.

41. George Gallup Jr., quoted in Religious News Service, “Gallup Says Americans ‘Spiritually Hungry,’ Reject Rationalism,” Religion, Washington Post, 13 May 1977, E6.

42. Religious News Service, “Spiritually Hungry,” E6; quoting George Gallup Jr.

43. See Doctrine and Covenants 88:132–33.

44. Kimball, “Education for Eternity.”

45. Doctrine and Covenants 42:14.

46. Joseph Fielding Smith, “Educating for a Golden Era of Continuing Righteousness,” BYU Campus Education Week address, 8 June 1971.

47. Kimball, “Education for Eternity.”

48. Dallin H. Oaks, “Accomplishments, Prospects, and Problems in the Centennial Year,” BYU Centennial: A Century of Love of God, Pursuit of Truth, Service to Mankind, 1975 BYU annual university conference speeches, 20 (26 August 1975).

49. See Kimball, “Second Century.”

50. Harold B. Lee, “The Mission of the Church Schools,” Ye Are the Light of the World: Selected Sermons and Writings of President Harold B. Lee (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1974), 104.

51. Student letter to Dallin H. Oaks, received 12 August 1977.

52. Student letter.

53. Doctrine and Covenants 93:24.

54. Kimball, “Second Century.”

55. Kimball, “Second Century.”

56. Kimball, “Second Century.”

57. Kimball, “Second Century.”

58. Kimball, “Second Century.”

59. Kimball, “Second Century”; quoting Articles of Faith 1:9.

60. Helaman 4:13.

61. Neal A. Maxwell, “Some Thoughts on the Gospel and the Behavioral Sciences,” Speaking Today, Ensign, July 1976.

62. Doctrine and Covenants 3:6–7.

63. Kimball, “Second Century.”

64. Kimball, “Second Century.”

65. Alma 34:20, 24.

66. Alma 34:25.

67. Alma 34:24.

68. Alma 37:37.

69. Doctrine and Covenants 88:63–64.

70. John Taylor, Deseret News, 1 June 1880, 1; see also John Taylor, Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 21:100 (13 April 1879).

71. Kimball, “Second Century.”

72. Spencer W. Kimball, “The Gospel Vision of the Arts,” Ensign, July 1977; see also Kimball, “Education for Eternity.”

73. Joseph Smith, History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 7 vols. (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-”day Saints, 1902–32), 3:381 (27 June 1839); also in Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, ed. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1972), 151.

74. Romans 8:31.

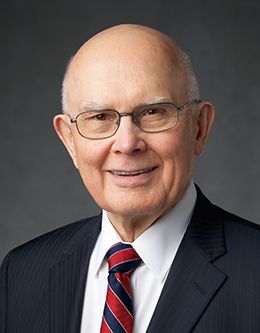

Dallin H. Oaks, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was president of Brigham Young University when he delivered this Annual University Conference address on August 31, 1977.